Chris Mason: Brexit means buck now stops with government on immigration

- Published

The conversation about immigration is characterised by a stumbling awkwardness.

Not just at Westminster. But in society at large.

Conflicts and contradictions, wherever you look and listen.

There are the numbers. There is the economics. There are the practicalities.

There are industries, there is the health service, and there are some parts of the UK keen to lure people in.

But this is a debate about emotion, sentiment, belonging, identity - and sometimes fear too: some communities rapidly altered; public services strained.

It has been a conversation that has been a near constant soundtrack to the Conservatives' 13 years in office so far, since 2010.

When the now Foreign Secretary Lord Cameron was prime minister, he promised to cut net migration to the tens of thousands.

It is a pledge that has never come close to being met and became a motivating factor for some to back Brexit.

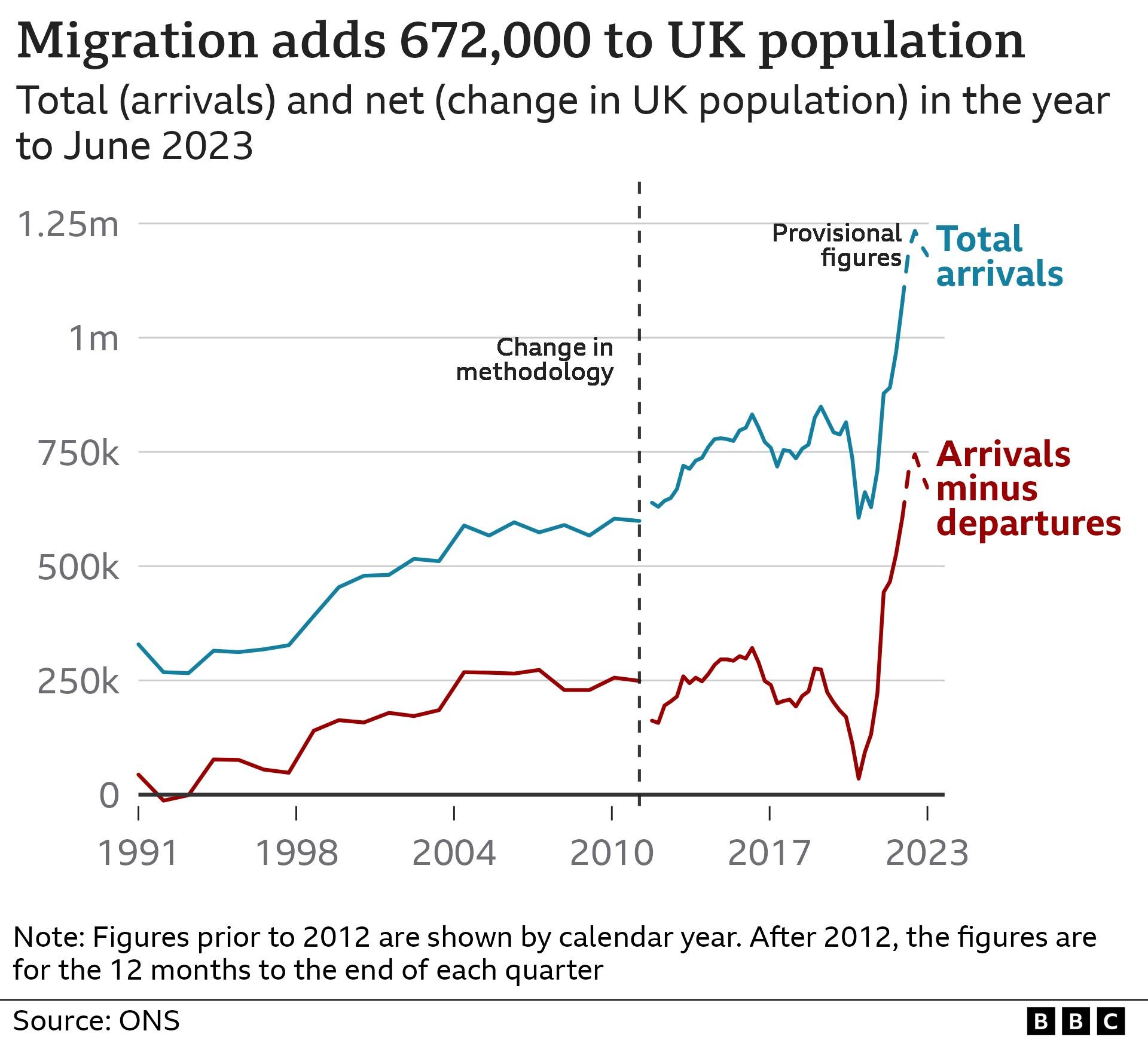

And yet net migration has soared since.

And that contributes to a ripple effect into other equally fraught political themes - such as planning, the demands for more housing.

The reaction of our political parties to these numbers is worth unpicking.

The Scottish National Party lashed out at what it sees as Westminster's obsession with driving the numbers down.

The SNP says Scotland needs more immigration of people of working age, not less - to help public services function and the private sector to thrive.

Compare that to the language of the Conservatives and Labour - and what comes across as an attempt to out do each other in their anger.

Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said the figure was "shockingly high".

The prime minister's official spokesman said it was "far too high".

Former Home Secretary Suella Braverman claimed the numbers were "unsustainable" and "a slap on the face to the British public".

And yet at the heart of all of this is an essential truth.

Brexit offers a clarity.

The responsibility for immigration policy, from anywhere, lies at Westminster.

The vote for Brexit may have been two general elections ago, in 2016, but the next election will be the first fought with the UK no longer a member of the European Union.

As a member of the EU, there was free movement of people around the club, including to and from the UK.

It meant politicians could, and did, blame it for not being fully in control of immigration.

But come the general election campaign, each party, for the first time, will have to set out its approach to immigration knowing where the buck now stops.

Each will have to articulate their instinct and attitude and their policies.

Each will know that if they form a government, the six monthly numbers published by the Office for National Statistics will be for them solely to justify, to defend.

They can no longer blame anyone else.

Related topics

- Published23 November 2023

- Published23 November 2023