The disruptive future of printing

- Published

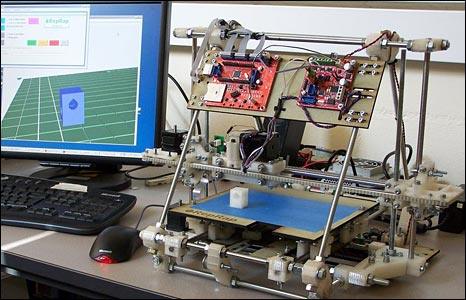

Will we all have printers like this in the future?

Printing solid objects is getting cheap and simpler, and the possibilities excite Bill Thompson

Imagine a school where a student could sketch out an idea for a new design of bicycle and not only draw it in 3D using a computer-aided design package but actually create a scale-model and test it out, using inexpensive materials and a special printer that they can build themselves in the classroom.

That's the vision put forward by Ben O'Steen, a software engineer with a social conscience who is thinking about the implications of a world where 3D printers are no longer just expensive prototyping systems for large companies but have fallen into the hands of the masses.

He has been inspired by the RepRap, a desktop 3D printer capable of printing plastic parts by extruding a heated thermoplastic polymer under computer control, which then sets as it cools and makes a usable object.

The RepRap project was started in 2005 by Adrian Bowyer, who teaches mechanical engineering at Bath University.

The schematics and all aspects are freely licensed for anyone to implement or adapt, and the current version, called "Mendel", can be built for around £350.

It makes objects from a cheap plastic made from corn starch, so is well within school budgets.

Future's here

The project has inspired thousands of people around the world, with websites dedicated to helping people make their own RepRap and get it working, and online schematics for objects from coat hangers to working whistles to models of Gothic cathedrals - that one is available at a website called the 'Thingiverse'

Although I'd come across the RepRap before it had always been an abstract idea, but seeing Ben talk - at a recent conference organised by the Open Knowledge Foundation - with such enthusiasm about its potential in education and elsewhere brought home its transformative potential, and made me realise that the future has already arrived, even if it is not yet widely distributed.

And while a technology that offers people the ability to manufacture complex objects at home or in the office is enormously disruptive, we can at least see this one coming.

Some writers of speculative fiction have already started engaging with it, including Bruce Sterling, in his lovely short story "Kiosk", and Cory Doctorow, whose novel "Makers" offers us an imagined world of printed objects and an emergent culture of 3D makers who directly challenge many of the core assumptions of industrial society.

I heard Ben speak about the RepRap, along with many other programmers, scholars and activists committed to making all kinds of information available to be freely used, reused, and redistributed, from "sonnets to statistics, genes to geodata" as their website puts it.

His talk was the highlight of the day for me, partly because he had brought a collection of props with him but also because his focus on real-world objects bridged the gap between the sometimes dry discussion of open databases and LinkedData and the day-to-day experiences of the vast majority of people whose lives don't revolve around technology.

As with so many advocates of free and open source solution, Ben and his friends are also planning to turn engagement into action by offering to help groups that want their own RepRap get off the ground by printing off the plastic parts needed to build your own.

Because one of the really exciting things about the RepRap is that it can make its own parts, or at least it can make the plastic ones - you can't yet print circuit boards or metal components - so once someone has one they can help to spread the technology.

Just as the easy availability of powerful computers, large hard drives and fast networks has exposed the inadequacies of copyright laws designed in an age when infringement required a printing press or a CD-burning factory, 3D printing will soon come up against laws made in a world of factories and machine tools, and the battle is likely to be even more intense than that over music and films.

Fortunately for those of us who believe in open data and an open society the intellectual ground for a remodelling of old forms of regulation is already being prepared by the Open Knowledge Foundation and others, so I'm slightly optimistic that we won't be arguing about the provisions of the "Digital Modelling Bill" in ten years time.

Bill Thompson is an independent journalist and regular commentator on the BBC World Service programme Digital Planet. He is currently working with the BBC on its archive project.