Greg Norman: Great white business shark

- Published

Golfer Greg Norman has a broad-reaching business empire built around the sport

Golf legend Greg Norman is a busy man, looking after his Great White Shark Enterprises multinational business.

The two-times British Open golf champion has reached a level of business success few, if any, of his contemporaries have matched, with an empire that covers everything from golf course design to beef products.

This week his golf course design work has taken the Australian from his US home to the Gulf state of Oman, to oversee a development there, before flying on to Turkey for a golfing award and then home.

For, as a major sporting icon turned business brand, Mr Norman is in demand - indeed only a few weeks ago the multi-millionaire was in China addressing sport and tourism officials about the potential growth of golf.

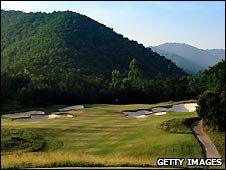

Dune course

Mr Norman has been in Oman this week to oversee work at the Wave course in Muscat, the state's first PGA Links golf course.

"It is coming along great," he tells the BBC. "It is a really good location for golf course design, right next to the ocean and I am also able to put some of the holes in among the sand dunes.

"I have truly enjoyed crossing over from sport to business. I enjoyed golf, where I experienced success through using my clubs, and now it is great to have my fingerprints all over new golf courses."

Mr Norman first got involved in golf course design in the late 1980s when he acted as advisor to Ted Robinson on courses in Hawaii and Chicago, giving a player's point of view to the designer.

"I was able to make it tougher in places for players, or easier in others, and after that I then started my own golf course design consultancy," says the player known as the Great White Shark.

'Living brand'

But how has he managed, from this initial start, to make the cross over to business with an empire that now includes everything from real estate to clothing, wine and restaurants?

"In 1993 I gave myself a seven-year game-plan into 2000, as I realised I would then be 45 years old and did not want to become a 'ceremonial golfer'," he says.

"I started planning my business, and promoting my image and brand, and after four or five years it was all going so well that I was able to stand back and play just a few golf tournaments, and focus more on my business."

Norman's shark logo is well-known in the world of golf leisure

Mr Norman says that despite his wide-ranging interests now, at first it was difficult convincing people that he should be involved in business.

"I built a brand around myself, I became a 'living brand'," he says, pointing to a major breakthrough on his business journey, the formation of the Greg Norman Collection clothing line in conjunction with Reebok back in the early 1990s.

"That was when my image took hold and then expanded.

"Since then there has been the integration of my other business interests, and my shark logo is recognised around the world, with for example wine, beef, real estate."

His hero in this respect is 1930s tennis player Rene Lacoste, who made sure his little crocodile logo was remembered around the world long after his death.

'Product space'

Like Lacoste, Mr Norman has found the discipline involved in sport useful in business, including, he says, "due diligence and research".

In business that also involves making sure that he is totally comfortable with getting involved in any new venture, including licensing deals, and avoiding anything that might damage his brand.

"I have to own my product space, if I can't validate products or services then they are not for me," he says.

"You have to have credibility as a brand, and underneath that you need a solid base, which for me was the Greg Norman Collection."

One golf brand that has been damaged in the past few months has been that of golfer Tiger Woods, who saw a number of his endorsements disappear after revelations of affairs.

He is now making a comeback in competitive golf - one very much in the media spotlight.

"When you are the number one player in the world you have to manage everyone's expectations," says Mr Norman.

"When you are at the top of the heap - Tiger put himself in a difficult position - you can tarnish an image.

"You can come back out of it, but it depends on the residual amount of feeling from what has gone before. Time will tell, but he has got to perform.

"There will be some negativity, there was before - when you are at the top of the heap in golf there will always be people pulling against you."

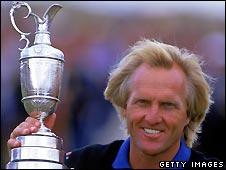

Lifetime Achievement award

Mr Norman himself spent more than 300 weeks as the world's number one golfer in his heyday in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Mr Norman's business includes golf course design

In recognition of his achievements he will this week accept the Lifetime Achievement award at KPMG's seventh annual Golf Business Forum in Belek, Turkey.

And it is those fans who followed him over the years who are very much his target customers.

"We have got to make sure are always flexible, but there was a group of people, babyboomers, now in their late 40s to early 60s who grew up with me," he says.

"But you have always got to understand your consumer, whoever it is, which is why I am very hands on when we establish things like new clothing or wine."

Chinese opportunities

Having become a well-known brand in the West, Norman finds that his attention is being drawn to the potential boom in golf in China.

The game is growing massively there at present and he says that the Chinese authorities envisage a total of 30 million players by 2020.

"The authorities are particularly active to build up golf now that it is an Olympic sport," he observes.

"The Olympics are going to have a huge impact on golf in places like China and India, and the Gulf."

As well as creating further opportunities for golfing entrepreneurs such as Mr Norman, the Olympics should also give golf a chance to boost its profile.

"Golf is going to find it hard to ever challenge football, which is huge," he says.

"But with the Olympics and growth of golf in China I can see it in the top two or three sports in the world in the coming decades."

Cost conscious

However, for now the golfing industry, like many others, is having to cope with the fallout from the economic downturn.

Greg Norman after winning the British Open for the second time in 1993

"Golf course design and real estate were affected big time," he says.

"Now there are so many people left on the sidelines with projects that are ready to get going, but they are bogged down because banks won't release funding."

He says that in such an environment golf course developers are becoming more sensitive over construction and maintenance costs.

Meanwhile, will he be playing in this year's British Open, the tournament he won twice, in 1986 and 1993?

"At 55 I generally don't like standing around for eight hours a day, often in the cold," he says.

"I have entered the Open so we will take it from there. I have just had shoulder surgery, but hope to be playing again in a week."