How did Thailand come to this?

- Published

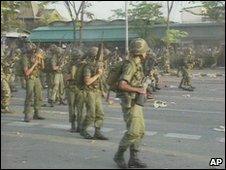

Troops used armoured vehicles to smash through the protest barricades

Three months ago, Bangkok appeared to be a successful South East Asian capital city - now government troops and anti-government protesters are fighting in the streets. The BBC's Vaudine England considers how it came to this.

Huge and thriving, Bangkok has long been seen - and seen itself - as a great city. But now there is blood on the streets.

It is hard to imagine how Thailand got to this - and how it will manage to recover.

One explanation is simply that a crazed rabble of poor people came to the city from the under-developed north, flauning their love for a former prime minister - Thaksin Shinawatra - and being paid to do so.

Another vision talks of class war and a peoples' uprising, as the masses rise up on the barricades.

The reality lies somewhere in between and can only be understood by a brisk walk through Thailand's recent political history.

It is easy to speak of the 18 new constitutions in the past half-century, and the many coups. It is hard for people living in more settled countries to imagine that level of uncertainty about the basic rules of the political game.

Absolute monarchy only gave way to constitutional rule in 1932 and the play of power between the old feudal system, the military and various democratic forces has been fought out ever since, often with fatal consequences.

Certain big dates stand out: 1973, 1976, 1992, 2006 and now 2010.

Thailand's overwhelming image as a Land of Smiles - as a fantasy land of sun, sea, sex and surgery - has been carefully crafted.

It has seduced many, outsiders and Thais, into believing a facade of stability where there was perhaps more a papering over the cracks.

That paper is now badly torn. Deep-seated fissures, long in existence, can no longer be ignored.

If nothing else, commentators agree, the red-shirts have achieved that much.

Bloody history

Thailand lived under variations of military rule most of the time since the 1932 constitution, during World War II, into the 1970s.

On 14 October 1973, more than 70 protesters were killed and 800 were injured when troops opened fire on huge demonstrations held in support of pro-democracy students.

The then military government collapsed; a new constitution and new elections in six months followed.

On 26 September 1976, two students were garrotted and hanged, allegedly by police. Thousands of students gathered in their support and against military rule.

Two weeks later, on 6 October, that tension exploded into the killing by soldiers, police and right-wing mobs of at least 46 people. Students said many more died.

This moment marked the end of a democratic period, and caused parts of a generation to flee to the hills, joining a communist movement which was later decimated.

Street fighting in 1992 left scores of people dead

By 1980, Gen Prem Tinsulanonda was appointed prime minister after a fellow general had ruled for three years following an October 1977 coup.

Gen Prem is now chairman of the Privy Council, and a target of red-shirt ire for what they claim was his role in the 2006 coup.

Coups and wobbly coalition governments led by appointed prime ministers carried Thailand into 1992, when Chamlong Srimaung led protests against the choice of Gen Suchinda Kraprayoon as prime minister.

King Bhumiphol Adulyadej famously called the two men into his presence to end fighting on the streets in mid-May that year, which had left scores dead, many injured and more than 2,000 people missing.

Back to future

Elections in September 1992 produced a Democrat-led coalition, with Chuan Leekpai as prime minister.

Thaksin Shinawatra proved very popular but highly divisive

Two years later, a telecommunications tycoon called Thaksin Shinawatra made his political debut, under the wing of Mr Chamlong.

In 1995, Mr Chamlong led his Palang Dharma party out of the coalition, causing the Chuan government to fall. Mr Thaksin was deputy prime minister in the next government.

Two coalition governments later, General Chavalit Yongchaiyudh was prime minister - he is now chairman of Mr Thaksin's Peua Thai Party.

The 1997 economic crisis brought back the Democrats under Mr Chuan. But elections in January 2001 gave Mr Thaksin a resounding win.

Mr Thaksin used this to accrue wealth and power across a range of Thai institutions. He earned a shocking human rights record and quashed the free press, but poured money into rural areas usually starved of attention.

In elections in 2005 he again won by a landslide, with the highest voter turnout in Thai history. He called another, snap, election in 2006, which the Democrat opposition boycotted. His win was ruled invalid by the constitutional court on 8 May 2006.

Plans for elections in October were foiled by the 19 September coup in 2006. Since then, two Thaksin-allied governments have been elected and stymied by court actions, leading to the current Democrat government, elected by another vote in parliament, not a general election.

Determining whether current troubles are sudden and shocking, or in fact an outgrowth of a long history of conflict - discussion of which has been suppressed by censorship and strict lese majeste laws - all depends on where you choose to start.

Whatever version of the recent past is chosen, neither violence nor a death-defying commitment to democracy is unusual in Thai politics.