Climate change is 'distraction' on malaria spread

- Published

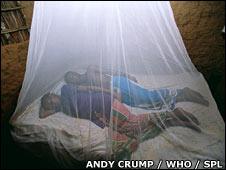

Mosquito nets are proving effective - where they are available

Climate change will have a tiny impact on malaria compared with our capacity to control the disease, a study finds.

Noting that malaria incidence fell over the last century, researchers calculate that control measures have at least 10 times more impact than climate factors.

Research leader Peter Gething from Oxford University described the climate link as an "unwelcome distraction" from the main issues of tackling malaria.

The paper, by scientists in the UK, US and Kenya, is published in Nature.

"We were looking to quantify something that perhaps we already knew with regard to the interaction of climate and malaria," Dr Gething told BBC News.

"A lot of the studies proposing there would be a dramatic increase in a warmer world have been met with guarded criticism, and often what's been said about them surpasses what the actual science indicates.

"So this redresses the balance a bit."

Reducing misery

The starting points for the research are other projects that mapped the range and endemicity of malaria across the world in 1900 and in 2007.

"Endemicity" is a measure of how far a disease penetrates through a population.

The last century saw deployment of anti-malarial drugs and a range of control measures, from marsh drainage to insecticides to bednets, across the tropical regions that are the disease's hinterlands.

Over the 107 years spanning these two studies, these measures were highly effective in curbing malaria.

They reduced its impact across virtually all of its range, and eliminated it in huge swathes of Asia, North America and Europe.

Yet all this happened during a century when the Earth's average temperature rose by abut 0.7C - raising the question of whether warmer temperatures and wetter conditions in some regions really would influence malaria transmission.

Plugging these figures into computer models of disease spread showed that control measures as deployed in the real world had an impact at least an order of magnitude greater than any climatic influence.

When deployed at optimum efficiency, they were about two orders of magnitude more influential.

"I'd say what we've shown is that if we can provide people with existing technologies such as drugs and bednets, we have the capacity as a global community to reduce the misery this disease causes," said Dr Gething.

"Climate change is, in our view, an unwelcome distraction from the main issues."

Uncertainty rains

Chris Drakeley, director of the Malaria Centre at the London School of Hygiene and Tropcial Medicine, suggested the group's conclusions were broadly correct.

"I am slightly sceptical of the furore surrounding (malaria and) climate change in the sense that we have to bear in mind there are other factors that are moving much faster than climate change," he said.

"I don't doubt climate change is happening, but we have also seen an increase in the coverage of treatment, and in the last 20 years there has been a huge amount of information and education on malaria made available in Africa; and that's all changed much faster than the climate."

Although individual studies and reports down the years have flagged up climate change as likely to increase the spread of malaria markedly, the 2007 Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report did not.

It concluded that although climatic change would alter the prospects for malaria, science could not yet predict where, when and how.

Climate change was very likely to "have mixed effects on malaria; in some places the geographical range will contract, elsewhere the geographical range will expand and the transmission season may be changed," it concluded.

While correlations had been observed between disease transmission and local climate changes in some regions, "there is still much uncertainty about the potential impact of climate change on malaria at local and global scales," it said.