From rubbish dump to school room in Mumbai

- Published

Many children work at the Govandi rubbish heaps rather than go to school

The suburb of Govandi in Mumbai (Bombay) is home to the Indian city's only rubbish dump. On any given day children work and play here, seemingly unaware of the scorching sun and the stench from the waste heaps.

Among them are probably some of the 8 million children who do not go to school across India. Few people notice their presence.

But in Govandi alone, more than 1,500 children are thought to be out of school.

Since April, education has become a fundamental right for children between six and 14 years old in India. This means that the law will support every child in demanding a free education.

That is the theory; the experience of Govandi shows that the reality is different.

Here, campaigners say the authorities must focus on those children who choose work over education. The challenge ahead is immense.

Lucrative pickings

Across the state of Maharashtra school drop-out rates have fallen to just over 2% from 6% in the last three years. But some children continue to give the classroom a miss.

In Govandi, many work on the dumping ground picking rubbish. They say they make anywhere from $1 (£0.6) to $6 (£4.16) a day.

"The children live so close to the landfill that it is impossible to avoid it. The dumping ground is where they eat, work, play and spend most of their time.

"They also make significant money," says Christine Charles of Pratham, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) working in education.

Social activist Mangal More says that money is the driving force: "When we tried to persuade them to not work there, they said 'we make more money than you'!"

The dump also draws children because of the variety of food which hotels deposit there at the end of the day.

"Chinese food is our favourite," one child says.

They sometimes also find tobacco packets, wafers and biscuits which they sell.

Pratham has set up a drop-in centre nearby where children can come, play, study and spend time away from the dump.

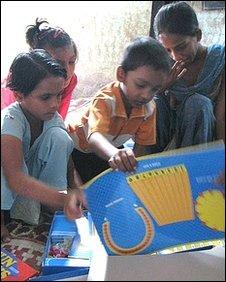

Activists say that children who attend centres eventually start learning

Amjad is about six years old and has been coming to the drop-in centre for a few months.

Even at this age, he knows he should not say he works at the dump.

"I only played there. My brother used to collect garbage. He is not here right now," he says.

Shehnaz Shaikh, a teacher at the drop-in centre, says one cannot force the children to study.

"Initially they just come, play and go. Sometimes they use the toilet, have a bath, look at the toys. Gradually they start developing an interest. Then we start teaching."

Education challenge

Once a child is prepared, he or she can take an examination for a municipal school and get admission to an appropriate class.

Activists say their work does not stop at getting a child into school.

Sanjoy Kishore, who has worked in the field of child labour and education says the quality of education in some municipal schools is mediocre.

"A child cannot grasp. Few can write a sentence correctly despite being in school for three to four years. Naturally, they drop out. So it is not just about convincing them to join school," he says.

That is where follow-up teams, which keep a record of a child's progress, come in.

"If a child is missing school then we go meet their parents and school teachers and try to sort it," Ms Charles explains.

However, sometimes helping out with studies is not enough.

Children say rubbish picking is a lucrative business

In certain cases children are relocated to a residential centre away from the city. They live with other children from similar backgrounds and complete their schooling.

Farukh Abdul Shaikh, 15, says four years at the shelter have been most rewarding.

"Earlier I used to work at the dumping ground for money. There was always something or the other which made me work. Since I have moved here, I don't feel that pressure."

His elder brother works as an electrician and his mother sells homemade food items.

Interested in playing the guitar and singing, Farukh wants to become a singer after he completes his education.

"I hardly visit the dumping ground now. I only meet family when I go there," he says.

"The children who could be convinced to attend schools have enrolled by now. These 1,500 children who remain outside are the real challenge as normal incentives have not worked for them," Kishore says.

Providing motivation

Educational expert Farida Lambe says a long-term holistic approach is needed where financial needs of the family are taken into consideration.

"A complete 'no' to labour for children under 14 years is crucial. Simultaneously, the government should provide an enabling environment in schools so that children are retained."

Maharashtra Education Secretary Sanjay Kumar says handling drop-outs are a real challenge and measures like awareness campaign have been planned.

"We cannot compensate for the wage loss in the case of children who work, so it is important to motivate them," he says.

"There are allowances, uniforms, midday meals, attendance allowances, scholarships. If one generation becomes literate, completes education, gets jobs, then they will be convinced. It is a long-term process."