Q&A: The meaning of synthetic life

- Published

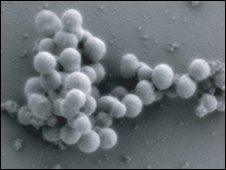

The synthetic DNA is in complete control of the new cells

Researchers in the US have developed the first synthetic living cell. Their work, which many scientists have called a landmark study, is a key step towards the design and creation of new living things. BBC News examines the issues raised by this controversial breakthrough.

Have these scientists created synthetic life?

They are calling this a synthetic living cell. But they did use an existing cell as a template and as a recipient for their home-made DNA. Strictly speaking, it is only the genome - the DNA in the cell - that is entirely synthetic.

This bacterial cell, the researchers say, is the first life form to be entirely controlled by synthetic DNA.

The researchers also employed "nature's tools" to build their new chromosome (the package of DNA that contains all of the genetic material the cell needs to live and function).

They chemically constructed blocks of DNA then inserted them into yeast cells, which assembled the blocks into a complete bacterial chromosome.

What will the scientists do with these synthetic bacteria?

These particular cells are just copies of existing or "wild type" bacteria. But they show that making a living cell with a synthetic chromosome is possible. Dr Craig Venter and his colleagues hope to use this technology to design new bacteria from scratch - cells that could carry out useful functions.

He and his colleagues are already collaborating with pharmaceutical and fuel companies to design and develop chromosomes for bacteria that would produce useful fuels or even new vaccines.

They say they hope eventually to "build" bacteria that absorb carbon dioxide and therefore help repair damage to the environment.

Could they use this same technique to make more complex synthetic organisms - like plants or animals?

Theoretically, yes. But the current aim is to design and build bacterial cells.

They are an ideal first candidate because they could potentially produce substances that we want. Dr Venter believes such tailor-made bacteria could "create a new industrial revolution".

And, in genetic terms, bacteria are very simple organisms.

They typically have a single, circular chromosome of DNA. On the other hand, every single cell in the human body contains 23 pairs of much larger, linear chromosomes. So bacteria have much less information in their genomes and it has been possible to sequence and copy all of this information.

Dr Venter says that extending the technique to higher organisms, such as plants, might be possible, but it will take scientists many years to work out how to build such large and complex genomes.

Are there ethical concerns about making new life?

Some critics have accused Dr Venter and his colleagues of "playing God" and believe that it should not be a role for humans to design new life.

There are also concerns about the safety of this new technology.

Professor Julian Savulescu, from the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics at the University of Oxford says the potential of this science is "in the far future, but real and significant: dealing with pollution, new energy sources, new forms of communication".

"But the risks are also unparalleled," he continues. "We need new standards of safety evaluation for this kind of radical research and protections from military or terrorist misuse and abuse.

These could be used in the future to make the most powerful bioweapons imaginable. The challenge is to eat the fruit without the worm."

Dr Venter stresses that he and his colleagues have been addressing these ethical and safety issues since they began their first experiments in the field of synthetic biology.

"We asked for an extensive ethical review of the approach," he explained.

"In 2003, when we made the first synthetic virus, it underwent extensive ethical review that went all the way up to the level of the White House.

"And there have been extensive reviews including from the National Academy of Sciences, which has done a comprehensive report on this new field.

"We think these are important issues and we urge continued discussion that we want to take part in."

- Published20 May 2010