Japan launches Akatsuki probe to Venus

- Published

Japan has sent a sophisticated probe to Venus to study its atmosphere in unprecedented detail.

The Akatsuki orbiter was put on a path to the inner-world by an H-IIA rocket launched from the Tanegashima spaceport in the south of the country.

The vehicle left its pad at precisely 2158 GMT (0658 local time Friday).

Akatsuki will arrive at Venus in December. Key goals include finding definitive evidence for lightning and for active volcanoes.

It was the H-IIA's second attempt at a launch. A previous effort earlier in the week was aborted because of a thick covering of cloud at the Tanegashima facility.

Thursday's get-away, by contrast, was made into a bright sky. The 53m-high rocket climbed south-east over the Pacific Ocean, its lift-off timed to the second to make sure Atkatsuki picked up the correct trajectory to make it out to Venus.

The H-IIA vehicle had a busy flight. It also deployed five piggy-back experiments, including a small satellite to practise the technique of sailing on sunlight.

Once Akatsuki gets to Venus, it will not be alone. The probe will conduct joint observations with a European Space Agency craft - Venus Express - that arrived at the planet in 2006.

Planetary comparisons

Venus is almost identical in size to our planet, and is thought to have a similar composition. But there the resemblance ends.

The surface of Venus is hidden beneath thick cloud

A dense, largely carbon dioxide, atmosphere acts as a blanket, trapping incoming solar radiation to heat the planet's surface to an average temperature of 460C (860F).

Surface pressure is about 90 times that on Earth. Several Soviet probes sent to Venus in the 1960s were crushed as they approached the surface.

By studying this hostile world, scientists hope to understand better how a warming future on our own planet might evolve.

"Although Venus is believed to have formed under similar conditions to Earth, it is a completely different world from our planet with extremely high temperatures due to the greenhouse effect of carbon dioxide and a super rotating atmosphere blanketed by thick clouds of sulphuric acid," explained Takeshi Imamura, Akatsuki's project scientist.

"Using [Akatsuki] to investigate the atmosphere of Venus and comparing it with that of Earth, we hope to learn more about the factors determining planetary environments."

Volcano hunt

The thick Venusian atmosphere is opaque to instruments that operate at visible wavelengths and so the Japanese probe carries five cameras that are sensitive in the infrared and ultraviolet parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

This instrument suite will enable scientists to investigate the clouds layer by layer.

The Japanese team wants to get a better understanding of why Venusian weather systems moves so swiftly.

"On Venus, a high-speed wind called super-rotation is blowing all over the planet, in the direction of planetary rotation, with a velocity reaching 400km per hour at an altitude of around 60km from the surface," explained Dr Imamura.

"This wind blows 60 times faster than the planet's rotation, which is very slow (one full rotation takes 243 Earth days). Akatsuki will investigate why this mysterious phenomenon occurs. Another objective is to study the formation of the thick sulphuric acid clouds that envelop Venus, and to detect lightning on the planet."

Infrared sensitivity can also be used to study surface composition.

Akatsuki will use this capability to try to find active volcanoes.

Europe's Venus Express probe recently found lava flows that could have been younger than 250,000 years old.

Solar 'yacht'

Akatsuki's H-IIA rocket carried aloft a group of smaller satellites, some weighing just a few kilos.

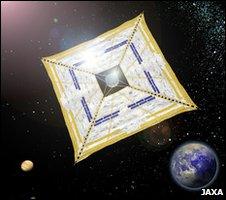

A lot of interest has centred on a solar sail project called Ikaros (Interplanetary Kite-craft Accelerated by Radiation Of the Sun).

An artist's impression of how Ikaros will look in space

In the coming days, this 320kg, 1.6m-wide, disc-shaped spacecraft will deploy an ultra-light membrane.

The pressure of sunlight falling on this thin film should drive the disc out to Venus behind Akatsuki.

This type of "solar sailing" technique has long been touted as a means of moving spacecraft around the Solar System, or even just helping conventional satellites to maintain their orbits more efficiently.

The large sail (14m along the square) will also incorporate solar cells to generate power.

The mission team will be watching to see if Ikaros produces a measurable acceleration, and how well its systems are able to steer the craft through space.

The Ikaros team acknowledges that deploying the large sail and controlling it will be extremely difficult.

"We conducted many experiments on the ground, and also launched the film aboard a sounding rocket," said project leader, Dr Osamu Mori.

"We even sent it high up in the sky in a big balloon, to spread the film in a near-vacuum environment. We experienced many failures, but we kept searching for the most reliable deployment method, and that led us to the model we've now built. I believe it will be successful."