Damaged Thailand considers the future

- Published

The capital is cleaning up after weeks of protest

After a brutal two months, with dozens of people killed in a political battle which seemed out of control, some Thais fear their society has been irrevocably damaged.

In the immediate aftermath of the military's move on the anti-government red-shirt protest camp, worrying talk sprang up of a threat of civil war and widespread insurrection.

People spoke of the burning hatred and division now marking Thai society.

Thai friends feel weepy about what has happened in their country - the shooting both ways between Thai soldiers and Thai protesters, the riots, the declaration of disaster zones in the heart of the city.

Many wondered how the country could come back from this trauma.

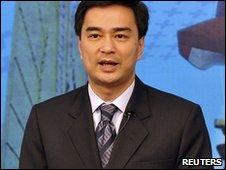

Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva has spoken of the need for rehabilitation and reconciliation, of his desire to speak to all groups in society.

Little time

A consensus of analysts suggests that Mr Abhisit has a small window in which to make some clear, genuine overtures to the foot soldiers of the red-shirt movement, if further trouble is to be averted.

These are not the militant among the red-shirts, who threw the firebombs, fired guns, and set fire to buildings.

These are the idealistic people who travelled from across the country to camp on Bangkok's streets, not for money but because of a powerful urge for justice and equality and their anger at what they call double standards.

The government continues to demonise the red-shirts as "terrorists", or mere followers of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra.

Analysts say this ignores the deep-seated issues brought to the fore by a broad-based movement for change.

One issue now is whether Mr Abhisit will be able to rise above the vicious feelings on both sides of this divide to lead genuine reconciliation efforts.

The deputy chairman of his Democrat Party, Kraisak Choonhavan, a former senator and active participant in civil society groups, insists Mr Abhisit's government has what it takes.

"I think this government is going to go ahead with its reforms, turning state policy towards social democracy… we need to see more acceleration of this," he said.

"Of course the government will be gentlemanly and will try to show the world that it is much fairer to the opposition than Mr Thaksin ever was," he said.

However, the time for impunity was past, he said; the Thai habit of letting bygones be bygones had to be left behind.

He said the key difference between the yellow-shirt protesters who helped to bring down former Thaksin-allied governments, and the red-shirts, was that the yellow-shirts did not burn buildings, did not attack the police and the army, did not have grenades and more.

Culture shift

Mr Kraisak alleged that the militant red-shirts, involved in the rioting and arson, "were the same people" as the movement leadership.

Certainly the red-shirts lost a swathe of support among a middle class that was beginning to see the larger issues at stake when militant members set fire to more than 30 buildings across Thailand.

But some analysts say a more concerted effort to understand where the passions come from has to be made, and soon.

A sociologist who asked not to be named said politics had been reduced to a zero-sum game in recent years, where the voices of a centrist civil society, public intellectuals and media have been squeezed into silence.

He recalled it had been similarly difficult not to be assailed by both sides of a bitter divide in the 1970s, and that it was the government's job now to expand the space available for voices which are neither "red" nor "yellow" to be heard.

Thai culture has gone through a dizzying transformation, he explained, in which old hierarchical values have been overturned through the processes of globalisation, communications and technology. Avoidance of confrontation, a belief in karma, the sacrifice of individual rights for a notion of the national good - all these have been weakened.

Thai villagers are no longer poor or uneducated - they want a larger slice of the economic pie, and they demand a voice, he said.

"Now is beyond the time to realise that these changes have occurred," the sociologist said.

The question is whether Mr Abhisit, and his colleagues in government, are capable of accepting and acting on this.

One positive aspect of the week's violence is that it might shock the ruling elite into looking more closely at such questions, an analyst suggested.

A failure by this government to be quickly inclusive, generous and responsive to the larger concerns behind the protests could lay the ground for far greater violence.

"The government can suppress the mob for a while," said Prof Amorn Wanichwiwatana, of Chulalongkorn University.

"But the Thai government should show sympathy and solidarity with all Thai people. There should be amnesty for all, not just the red-shirts, but everyone involved," he said.

Leadership

All this calls for a leadership not seen throughout the build-up and explosion of this crisis.

Mr Abhisit has to juggle the varying demands of his country and backers

Mr Abhisit is being "seriously squeezed", said commentator Dominic Faulder, as he tries to balance the demands of those who helped bring him to power, as well as his coalition partners, and other forces. "He is under huge pressure," Mr Faulder said.

"Mr Abhisit personally is an able man, but because of the way he stepped into power, he has not really had the power to make a decision," said Prof Amorn.

Prof Thitinan Pongsudhirak believes it is too late for Mr Abhisit. "He had his chance last year and has not been able to get the job done. In fact he has further alienated the reds," the political scientist from Chulalongkorn University said.

Those fearful of further violence argue that Thai society is more divided now than it was two months ago, because the protests lasted so long, and the denouement was so violent.

"The early post-mortem [of the military crackdown] is that the authorities feel vindicated and underlying that vindication is a vindictiveness.

"Of course you have to go after the arsonists but this government has never addressed the red-shirts' rank and file," said Mr Pongsudhirak.

Most Thais do not want violence or anger or fighting in the streets and are appalled at what has happened in their country.

If this government cannot grab this moment to reach out to this middle ground, analysts warn, then there are people ready to further radicalise the red-shirt movement.