Profile: Craig Venter

- Published

Craig Venter is one of science's more colourful characters

"Maverick" is a word that seems to follow Craig Venter around.

The biologist and entrepreneur turned the effort to map the human genome into a competitive race and, in so doing, was vilified by the scientific community.

Dr Venter has certainly not gained a reputation for modesty about his achievements. "Is my science of a level consistent with other people who have gotten the Nobel? Yes," he was once quoted as saying.

And he is a very wealthy user of Lear Jets and private yachts.

But his efforts in the field of human genomics have undeniably helped speed up the entire process.

After the publication of the human genome, Dr Venter turned his attention to another grand project: the creation of a synthetic life form.

Scientists at the US-based J Craig Venter Institute have been busily working on the endeavour for more than a decade. They have now published details of the result, an organism called Synthia, in the prestigious journal Science.

Born in 1946, as a boy, Dr Venter did not exemplify good scholarship and at 18 he chose to devote his life to the surfing pleasures of the beaches in Southern California. Three years later, in 1967, he was drafted into the Vietnam conflict.

As an orderly in the naval field hospital at Da Nang, he tended to thousands of soldiers wounded during the Tet offensive.

This inspired two important changes in him: a determination to become a doctor and a conviction that time should never be wasted.

"Life was so cheap in Vietnam. That is where my sense of urgency comes from," he said.

Need for speed

During his medical training he excelled in research rather than practice. By the 1980s, the early days of the revolution in molecular biology, he was working at the government-funded US National Institute of Health and soon realised the importance of decoding genes.

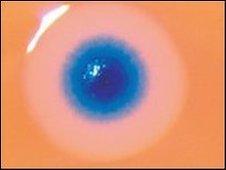

Dr Venter says the synthetic cell could spark an industrial revolution

But the work was messy, tedious and agonisingly slow. So, in 1987, when he read reports of an automated decoding machine, he soon had the first one in his lab. This speeded things up - but not enough.

Then came Dr Venter's real breakthrough. He realised that he did not need to trawl the entire genome to find the active parts, because cells already use those parts naturally.

He switched his attention from the DNA blueprint to the messenger molecules (called RNA) that a cell makes from that blueprint. He was then able to churn out gene sequences at unprecedented rates.

His success shocked some, most notably the co-discoverer of DNA, James Watson, who famously dismissed the relatively crude results obtained as work "any monkey" could do.

The criticism, and the failure to secure further public research funding, prompted Dr Venter to leave the NIH in 1992 and set up a private research institute, The Institute for Genomic Research.

And, in 1995, he again stunned the scientific establishment by unveiling the first, complete genome of a free-living organism, Haemophilus influenzae, a major cause of childhood ear infections and meningitis.

His greatest challenge to the establishment came in May 1998, when he announced the formation of a commercial company, Celera Genomics, to crack the entire human genetic code in just three years. At that point, the public project was three years into a 10-year programme.

Industrial revolution?

Both efforts published their results in 2001. What some saw as Dr Venter's disregard for scientific conventions such as open access to data brought him opprobrium in some circles.

Nevertheless, the financial rewards were enough to leave him in a highly unusual position for a scientist - with enough money and resources to do the science he wanted without having to tap the usual bureaucratic sources for funding and infrastructure.

In 2006, he formed the J Craig Venter Institute which would spearhead the labour to create the world's first synthetic life form. Dr Venter kept the scientific journals and the media abreast of developments, trumpeting several key advances as he edged closer to his goal.

But he has pursued other projects in the meantime. Dr Venter has roamed the oceans in his yacht, Sorcerer II, collecting life forms in an unprecedented genetic treasure hunt.

The project aims to sequence genomes from the vast range of microbes living in the sea, to provide scientists with a better understanding of the evolution and function of genes and proteins.

The synthetic life breakthrough, when it was announced, was not without controversy. But Dr Venter will have come to expect that.

"I think they're going to potentially create a new industrial revolution," he said of the synthetic microbes.

"If we can really get cells to do the production that we want, they could help wean us off oil and reverse some of the damage to the environment by capturing carbon dioxide."

- Published20 May 2010