Flash floods destroy Bangladesh livelihoods

- Published

Animals are rescued and ferried to higher ground to escape the floods

Soggy fields surround Wasib Ali's village when he wakes at 0530, yet he is not unduly concerned.

Usually the water evaporates in the heat within a couple of hours, so he gets up to release his livestock, which has been locked up for the night to protect it from wild dogs - and rustlers.

The ducks flap their wings as they head for the water, but the cows and sheep are more reluctant as they walk down the concrete steps that Mr Ali has built from the front of his house to the land he owns below.

Sheep are not keen to be herded into the soggy fields

As Mr Ali and his fellow villagers in Habid Pur emerge to begin their daily routines, they are blissfully unaware of the turmoil that is about to be unleashed.

Rather than dry out, the water keeps on coming so, within hours, the paddy fields are swamped and the rice damaged beyond repair before it can be harvested.

And so the villagers are left without food to sustain them for the next six months, without any surplus rice to sell, and without fodder for their animals.

Taken by surprise

At 0900 Mr Ali goes to the local market at Jawar Bazar to buy some groceries and to meet his friends over a cup of sweet tea.

But as the district has been without electricity for four days, he has been unable to charge his mobile phone, so it is only when a young boy comes looking for his father that he realises the water is still rising.

He hastens back to the village, where he finds a hive of activity.

People are quick to take advantage of the fish that come with the floods

Although the area floods for six months every year and unseasonable storms are common, farmers have been caught unawares as water from overburdened rivers rushes down. Soon the water rises to cover Mr Ali's ankles.

Time is tight now, so everyone rushes into the fields to cut the rice before it is completely covered in the murky swamp.

The rice itself is not yet ready for harvesting and the entire crop will be lost, but at least the stalks can be used for animal fodder in the months ahead.

Next, the animals that are stranded in the fields have to be rescued and taken to higher ground.

The water continues to rise. Two hours later, it is a metre high and lapping half-way up Mr Ali's steps.

A man emerges from the water with leeches attached to his legs and there are snakes in the water, yet the children keep on playing in what has become an enormous lake, their carefree existence contrasting sharply with their parents' concerned faces.

For many families here, selling rice or the milk produced from their cows is often their only form of income, so many fear for the future.

Questionable aid

The Dhaka government has contingency plans for such occasions, although there are critics of the service it offers.

Under their Vulnerable Group Feeding (VGF) scheme, initiated in 1975 after the famine that affected millions a year earlier, aid is targeted at households that earn less than $5 a month, lack agricultural land or productive assets.

When aid is needed, about six million people should benefit from the scheme.

But many villagers are unaware of the programme and have never received any aid at all.

The flooded fields provide a giant swimming pool for the children

"Government aid disappears before it reaches our region and nobody in our village has ever received anything," says Mr Uddin.

According to the World Bank Report, such concerns are widespread.

"A large share of resources appear not to reach their intended beneficiaries, indicating serous accountability problems," the Bank says in a report that outlines how illicit sales en route to the distribution centres - referred to as leakage - are the biggest problem.

Higher food costs and numerous natural disasters over recent years have also contributed to the difficulties of implementing the government's programme effectively.

Mr Ali is well aware of the difficulties ahead, so he decides to sell three of his six cows. The money he is paid for the cows should help sustain him for the next half a year and he will also have fewer animals to feed.

Perennial problem

But coping this year will do little to help him deal with a problem that keeps on occurring, year after year.

Whereas barriers against flooding can be built in the southern regions of the country, it cannot be done in the north.

"If we prevent the land from flooding us, it will only flood our neighbours instead," says local market trader Shakir Chowdhury.

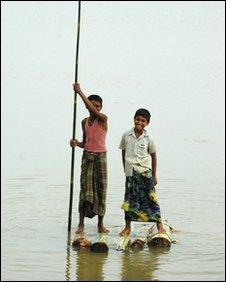

Bamboo poles strapped together provide an ideal form of transport

There have been efforts to introduce a strain of rice that can survive under water - and therefore still be harvested, even when submerged by flooding.

Most of those strains tend to originate in China and there is a reluctance to adopt them.

"The problem," says Mr Chowdhury, "is that we are accustomed to eating one kind of rice and people are not happy to change their cultural habits."

Meanwhile, families will have to endure the shortage of food and they will have meagre resources, if any at all, to purchase the seeds for planting next year.