Creative minds 'mimic schizophrenia'

- Published

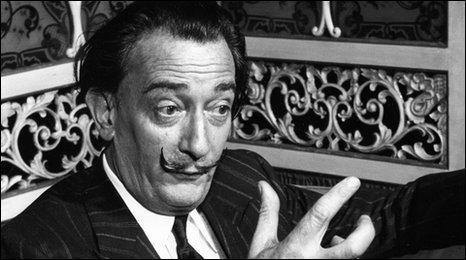

Artist Salvador Dali is known for his surreal paintings and eccentric personality

Creativity is akin to insanity, say scientists who have been studying how the mind works.

Brain scans reveal striking similarities in the thought pathways of highly creative people and those with schizophrenia.

Both groups lack important receptors used to filter and direct thought.

It could be this uninhibited processing that allows creative people to "think outside the box", say experts from Sweden's Karolinska Institute.

In some people, it leads to mental illness.

But rather than a clear division, experts suspect a continuum, with some people having psychotic traits but few negative symptoms.

Art and suffering

Some of the world's leading artists, writers and theorists have also had mental illnesses - the Dutch painter Vincent van Gogh and American mathematician John Nash (portrayed by Russell Crowe in the film A Beautiful Mind) to name just two.

Creativity is known to be associated with an increased risk of depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

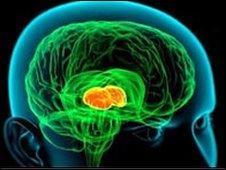

The thalamus channels thoughts

Similarly, people who have mental illness in their family have a higher chance of being creative.

Associate Professor Fredrik Ullen believes his findings could help explain why.

He looked at the brain's dopamine (D2) receptor genes which experts believe govern divergent thought.

He found highly creative people who did well on tests of divergent thought had a lower than expected density of D2 receptors in the thalamus - as do people with schizophrenia.

The thalamus serves as a relay centre, filtering information before it reaches areas of the cortex, which is responsible, amongst other things, for cognition and reasoning.

"Fewer D2 receptors in the thalamus probably means a lower degree of signal filtering, and thus a higher flow of information from the thalamus," said Professor Ullen.

He believes it is this barrage of uncensored information that ignites the creative spark.

This would explain how highly creative people manage to see unusual connections in problem-solving situations that other people miss.

Schizophrenics share this same ability to make novel associations. But in schizophrenia, it results in bizarre and disturbing thoughts.

UK psychologist and member of the British Psychological Society Mark Millard said the overlap with mental illness might explain the motivation and determination creative people share.

"Creativity is uncomfortable. It is their dissatisfaction with the present that drives them on to make changes.

"Creative people, like those with psychotic illnesses, tend to see the world differently to most. It's like looking at a shattered mirror. They see the world in a fractured way.

"There is no sense of conventional limitations and you can see this in their work. Take Salvador Dali, for example. He certainly saw the world differently and behaved in a way that some people perceived as very odd."

He said businesses have already recognised and capitalised on this knowledge.

Some companies have "skunk works" - secure, secret laboratories for their highly creative staff where they can freely experiment without disrupting the daily business.

Chartered psychologist Gary Fitzgibbon says an ability to "suspend disbelief" is one way of looking at creativity.

"When you suspend disbelief you are prepared to believe anything and this opens up the scope for seeing more possibilities.

"Creativity is certainly about not being constrained by rules or accepting the restrictions that society places on us. Of course the more people break the rules, the more likely they are to be perceived as 'mentally ill'."

He works as an executive coach helping people to be more creative in their problem solving behaviour and thinking styles.

"The result is typically a significant rise in their well being, so as opposed to creativity being associated with mental illness it becomes associated with good mental health."