Mobile banking closes poverty gap

- Published

Many people trust mobile banking services more than banks

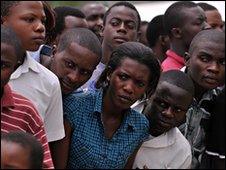

Mobile banking has transformed the way people in the developing world transfer money and now it is poised to offer more sophisticated banking services which could make a real difference to people's lives.

Currently 2.7bn people living in the developing world do not have access to any sort of financial service. At the same time 1bn people throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia own a mobile phone.

As a result, mobile money services are springing up all over the developing world. According to mobile industry group the GSMA there are now 65 mobile money systems operating around the globe, with a further 82 about to be launched.

Most offer basic services such as money transfers, which are incredibly important for migrant workers who need to send cash back to their families.

M-Pesa in Kenya is perhaps the most famous of these and it has attracted 9.4 million Kenyans in just under three years.

Now it is ready to move to the next stage. M-Pesa, has recently partnered with Kenya's Equity Bank to offer subscribers a savings account, called M-Kesho.

Money Matters

It means their M-Pesa accounts will no longer be just about money transfer. Instead, they will become virtual bank accounts, allowing customers to open saving accounts, earn interest on their money and access credit and insurance products.

It is an extension to an earlier agreement with Equity Bank to allow M-Pesa customers to access their funds at ATMs around the country.

CGAP, a financial think tank based at the World Bank, was at the launch of M-Kesho.

"Kenya is sending a message to the world: poor people want savings accounts. Mobile banking is a powerful way to deliver savings services to the billion people worldwide who have a cell phone but not a bank account," said CGAP chief executive Alexia Latortue.

Meanwhile in Uganda, MTN, a mobile firm that runs a similar mobile money service has ratcheted up 890,000 users in its first year of operation. This is double what it forecast.

Richard Mwami, head of mobile money at MTN predicts the service will have 2m users by the end of the year, and 3.5m by 2012.

He admits that one of the biggest challenges of setting up the system was regulating the agents that provide the cash.

"We have had liquidity problems where customers walk into the shop and there is no money," he said.

And fraud is also a problem, running to one or two cases every couple of weeks.

Some 60% of users live in rural areas, where literacy rates are low and agents are often local shopkeepers, authorised to take deposits and issue cash.

"There is ignorance about how the service works," he said.

MTN has now begun an education programme, promoting and explaining the service on national radio.

Only 38% of Ugandan citizens have a bank account.

Micro-economy

Gavin Krugel, head of mobile money at the GSM Association (GSMA) believes agents are more trusted than traditional banks.

"Banks have revolving doors and armed security guards. Consumers believe they are for the rich only," he said.

By contrast, agents tend to be trusted retailers who have been selling airtime to the same customers for the past ten years.

"Every one of the agents are trained and those that misbehave are taken out of the system," he said.

Aletha Ling, executive director of Fundamo, the platform behind MTN Uganda's mobile system, said the challenges are worth it because it is easy to see how it is benefiting customers.

"Money gets sent from the cities to the rural areas where it is required. Less cash passes hands so it is much more secure. Previously people were travelling with huge amounts of money," she said.

"In one fishing village I visited it had created its own micro-economy," she said.

In Uganda the banking population is low with only 38% having a bank account and only 7% using more than one banking product.

Mobile banking can also provide a route out of poverty, according to the newly-appointed UK International Development Secretary Andrew Mitchell.

Commenting on the GSMA's mobile money summit in Rio de Janeiro this week he said:

"Access to basic financial services - the ability to save, transfer and invest even small amounts of money - can make a huge difference to people around the world. It can help a farmer to survive a bad harvest, or provide a slum-dweller with the vital capital needed to start a small business,"

This is a view echoed by Mr Mwami.

"The mobile phone is demystified. People are confident about using it and the market is there for the taking," he said.

Disruptive technology

Last year Bill Gates pledged $5m to help the world's poor access banking accounts. The Mobile Money for the Unbanked Fund is being administered by the GSMA Foundation.

It has announced the projects which will benefit from the money.

It includes Bangladesh's Grameenphone which hopes to enhance its mobile money service with services such as a mobile ticketing service for Bangladesh Railways.

Money will also go to Orange Money to introduce more advanced financial services in Western Africa, where less than 4% of the population have banking.

Safaricom, the mobile firm behind M-Pesa, will get a grant to help non-government organisations and the Kenyan government get much-needed money to vulnerable households in informal settlements in Nairobi.

In Cambodia, the majority of payroll is given in cash and Cellcard is hoping to set up money transfer, bill payment and airtime top-up to urban migrants desperate to send money home to famiies in rural areas.

Similar projects in Pakistan, India, Sri Lanka and Fiji will also also benefit from the fund.

Mobile banking is a slow burn, said Mr Krugel, but a potentially revolutionary one as long as it is born from what consumers ask for.

"In many of these markets offering a fully-fleged bank account would be a waste of time. Consumers need to understand the basics first," he said.

"At first they don't trust the system. Then they can see that it works and eventually they start to leave some money in their account. This is how they start lifting themselves out of poverty," he said.

The next stage is more sophisticated services such as funeral or hospital insurance.

"In African culture, for example, they believe strongly in respect and funeral insurance is extremely important," he said.

Traditional banks are now beginning to wake up to the threat posed by mobile services and are increasingly partnering with the mobile firms to tap the potential of a whole new market.

"M-Pesa was sufficiently disruptive that it forced the banks to respond. If the banks do see these services as a threat they will realise there is opportunity at the base of the economic pyramid and that is a job well done by the mobile industry," said Mr Krugel.