Promise, but daunting challenges for electric cars

- Published

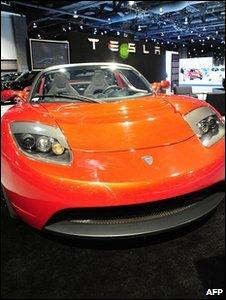

The Tesla is one of many electric vehicles

My knuckles were white gripping the steering-wheel and my hair was on end, but my driving credentials could not have been greener - I was at the wheel of a rocket-speed Tesla electric sports car.

With a 0-60mph acceleration of four seconds, this high-adrenaline experience blew away forever the stereotypical image of electric vehicles, the plodding milk-floats I'd known since my childhood.

But if battery power can be cool is it ever going to be practical? The question has urgent relevance as the coalition government declares its aim of pushing for an electron revolution on our roads.

A timely report by the Royal Academy of Engineering lays out the reality of turning some of Britain's 30 million cars electric in coming decades. The conclusion? The challenges are do-able but also pretty daunting.

As I listened to the study's chairman, Professor Roger Kemp of Lancaster University, and co-author Professor Phil Blythe of Newcastle University, the image of moving up through the gears came to mind.

So, getting started in first: can the batteries ever be made cheaply enough to tempt consumers? If they're big enough to get you a reasonable distance, they may add thousands to the price and potential consumers may think twice.

And how long will the batteries last? It depends on the type but typically they should be good for at least 1,000 charges which should give you at least three years' use.

And just as mobile phone batteries have become smaller and lighter, innovation should also drive improvements in vehicle power sources too.

Second gear, charging-up: some 4,000 charging points are due to be installed in pilot schemes in the North-east, Milton Keynes and London this year.

A good start, according to the authors, but what if you don't have off-street parking?

As Professor Kemp said: "You can't exactly have cables running out through the letter-box across the pavement into the street. And if it's raining, are you really going to park at a charging point a mile down the road from your house?"

'Chicken and egg'

Third gear, charging at your destination: what happens if thousands of electric car drivers descend on one spot - a football match, for example - and all want charging in the car park at the same time? Who pays for that infrastructure and who'll organise it?

Many issues need to be resolved around charging points

It's what Professor Kemp calls "a chicken and egg situation": charging-points won't be installed up and down the country until there are plenty of electric cars on the roads. And people won't buy electric cars until they'll be able to get a fill-up.

Fourth gear, the bills: at the moment, electric car ownership is encouraged with tax breaks. Right now, this doesn't cost the government much in lost revenue. But what if half the country's cars are exempt from Vehicle Excise Duty? How would the Treasury react then? The authors say a long-term policy on incentives is essential.

At current prices, a full charge for a typical electric car might cost about £2 - drawing enough power to drive about 161km (100 miles). Not bad compared to conventional fuel.

Finally, fifth gear, the carbon value: plug-in cars will only be as green as the electricity they're using. According to the report, electric cars powered by the current mix of sources are only "marginally greener" than the most economical petrol or diesel cars.

In an earlier report, the Royal Academy of Engineering had mapped out the scale of the task involved in moving to a low-carbon electricity supply - with a mix of energy efficiency, renewables, nuclear and clean coal. This new report adds urgency to the calls for decisions as soon as possible.

Speeding ahead

The key development, says Professor Kemp, alongside a move away from fossil fuels, is a so-called "smart grid". Backed by the coalition, this is an intelligent network in which demand better matches supply.

If cars were programmed to be charged at night, when demand is low, rather than at peak times, then their impact on power generation could be minimised.

So, what are the chances of our next cars being electric?

Professor Blythe, who's studying consumer reaction to battery-powered vehicles, reckons 5-10% of British cars will be electric within 10 years.

Just back from a motor show in Yokohama, he says the Japanese are at least a year ahead of us - even experimenting with "inductive charging" where cars can be refuelled without a cable connection but by parking over a special plate.

The potential for change is clearly massive but weaning British motorists off liquid fuel will be an uphill task, as the authors acknowledge.

"Cars are iconic," says Professor Kemp, "and central to our contemporary culture. In Britain, you would not get 6.4million people tuning in to TV programmes called Top Domestic Appliances or Top Condensing Boilers in the way they do for Top Gear."

Top Battery? Top Charging Point? Let's see.