Horned dinosaurs 'island-hopped' from Asia to Europe

- Published

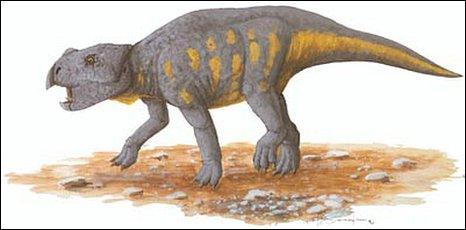

The newly found specimen is smaller than its American and Asian relatives

Horned dinosaurs previously considered native only to Asia and North America might also have roamed the lands of prehistoric Europe, say scientists.

Palaeontologists have announced the discovery of fossils belonging to a horned creature in the Bakony Mountains of western Hungary.

The find may give them a better understanding of the environment during the late period of dinosaur evolution.

They described their findings in the journal Nature.

The fossils of Ajkaceratops kozmai were found at a mine by a Hungarian team in summer 2009.

Team leader Attila Osi, from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, said that one of the fossils found resembles a parrot's beak.

At first he was unsure about the exact origin of the fossil, but it was confirmed to belong to a ceratopsian - a type of horned dinosaur - at a Bristol conference later that year.

"When I came back to Hungary from Bristol, I re-examined the complete collection of what we had discovered at that mine during the last 10 years," Dr Osi said.

"And among some 10,000 bones I finally discovered four other specimens that could be related to ceratopsians."

The newly found herbivore is a lot smaller than its American and Asian relatives, reaching only about a metre in length. It was a "dwarfed" member of the ceratopsian family, said Dr Osi.

Dinosaur fauna

While analysing the bones, the researcher consulted with other scientists, among them Richard Butler - a dinosaur expert based in Munich, Germany.

The fossils were discovered by a group of Hungarian scientists

Dr Butler, who is a co-author of the article published in Nature, believes the discovery is vital for the understanding of dinosaur fauna in Europe during the Late Cretaceous, some 100 to 65 million years ago. This was the last stage of dinosaurs' evolution before they went extinct.

"It's particularly important if we want to understand what dinosaurs in Europe were like at that time. It shows that horned dinosaurs were definitely present here," said the scientist.

The researcher explained that Europe in the Late Cretaceous was not a single landmass, but a group of islands known as Tethyan archipelago.

This was thought to mean that European dinosaurs were unique. But the new discovery might challenge that perception.

"The findings suggest that perhaps these animals were able to move between the two areas, meaning that European horned dinosaurs weren't so completely isolated," said Dr Butler.

His colleague agreed: "I think that these animals had to come to Europe from Central Asia during the Cretaceous," said Dr Osi.

He added that it is never easy to understand how animals move around in an archipelago, and the latest discovery could be "a very important piece of a big puzzle" that could help scientists create a better picture of prehistoric Europe and its ecosystem.

"It means that we now have to re-evaluate earlier concepts about the kinds of animals that inhabited this area," explained the palaeontologist.

Dwarfed island-hoppers

Dr Butler said that the newly found member of the ceratopsian family might have been a dwarfed animal, but it is difficult to say for sure, as all the scientists have for now are a few skull bones.

He explained that the phenomenon of dwarfing was quite common on the Tethyan archipelago. Animals were smaller than their continental relatives because of the limited resources of isolated islands.

"There's an evolutionary pressure for them to become smaller. It's something that's also known for elephants - there were dwarfed elephants living on islands in the Mediterranean a few tens of thousands of years ago," said the scientist.

And for horned dinosaurs to be able to move from island to island, they should have been good swimmers, said Dr Butler.

Either that, he added, or maybe at some point the level of the prehistoric Tethys Ocean that separated southern and northern continents was so low that islands were temporarily connected by land - and animals could basically walk on the sea floor.

Palaeontologists have been working at the site since 2000