Welsh ships' 'unsung' role in 1940 Dunkirk evacuation

- Published

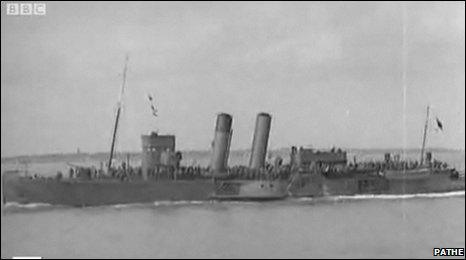

The Glen Gower rescued hundreds and survived - but was scrapped in 1960

As the nation celebrates the 70th anniversary of the evacuation of a third of a million Allied troops from Dunkirk, what is less well-known, even to the experts, was that several of those smaller boats and ships came from Welsh ports.

What Churchill called a "miracle of deliverance" began this week in 1940 after the German army's surprise attack through the Ardennes forest threatened to cut off the British Expeditionary Force.

Between 27 May and 5 June, the Royal Navy worked flat out, while the army fought a valiant rearguard action to delay the German advance and allow as many British and French troops as possible to escape.

The navy's efforts were supplemented famously by more than 1,000 civilian vessels, ranging from ocean-going ferries to little more than rowing boats.

One was the P&A Campbell paddle steamer Glen Gower which operated in the Bristol Channel, and is featured in Pathe news descriptions of the evacuation.

David Jenkins, maritime expert for the National Waterfront Museum in Swansea, said the records about the smaller boats or for those from farther afield is often quite confused.

He said: "The German advance through France only began on 10 May, so Vice Admiral Bertram Ramsay had little more than a fortnight to put together operation Dynamo.

"It was quite ordered at first, but as the pace needed to pick up, more and more vessels joined, and there wasn't always time to document them."

"Often we find out about the role of Welsh ships and boats from the recollections of rescued servicemen rather than official records.

Thousands of Allied soldiers were ferried to the big ships by the small ships

"It seems incredible that boats left Welsh ports, and were able to get to Dunkirk in time to play a part in the evacuation."

Yet it appears that many from Wales did answer the call, sailing hundreds of miles around Land's End to join the rescue.

Among them were The Scotia, a ferry more accustomed to taking passengers from Holyhead to Anglesey, and the Glen Gower, which until the war had idled its way around the Bristol Channel, making pleasure excursions for the tourists of south Wales and north Devon.

As a large, ocean-going ferry, The Scotia was requisitioned by the Royal Navy, and gained the prefix HMS Scotia.

She rescued thousands of troops from the make-shift jetty in Dunkirk, surviving unscathed after being struck by German shells and torpedoes.

Sitting target

However her luck eventually ran out when she was sunk on 1 June 1940. She and her crew are remembered in a special free exhibition at Holyhead Maritime Museum over half-term week.

"On her third run out of Dunkirk, and full of French, British, and Belgian troops, she was attacked by 12 enemy aircraft.

"A bomb from a dive bomber fell down the funnel blowing out the keel, and she was sunk with great loss of life."

John Cave, curator of Holyhead Maritime Museum, said: "Our Holyhead at War exhibition has displays and exhibits from the Scotia as well as for the other Holyhead ferries which served during the world wars of the last century.

"The additional temporary exhibition shows images from the evacuation of Dunkirk and the later stationing of the Dutch navy in Holyhead."

The paddle steamer Glen Gower fared better, despite her painfully slow progress and lack of manoeuvrability making her somewhat of a sitting target for Luftwaffe bombers.

'Abandoned'

She wasn't able to reach Dunkirk until the latter, and most dangerous stage of the operation in the first days of June, when boats were unable to use the jetty and had to come into the beach under intense German artillery fire.

Mike Mason, from Trellech, in Monmouthshire, a marine history enthusiast, said: "Despite having had her hull penetrated by an enemy shell, the Glen Gower managed to make it back to Harwich, having rescued hundreds of servicemen from the beaches at Dunkirk.

"She returned after the war to operate excursions on the Bristol Channel until 1959 and was scrapped in 1960.

"Three other P&A Campbell paddle steamers which had operated in the Bristol Channel, the Devonia, Brighton Queen and Brighton Belle, were not so lucky as they were all sunk at the time.

"The Devonia, in particular, was left stranded and abandoned on the beach at Dunkirk."

But the extraordinary evacuation was only made possible by the heroic efforts of the troops in northern France, who frustrated the German advance for long enough to allow their comrades to escape.

When the battle reached the town of Dunkirk, the fighting was often conducted hand-to-hand, defending each street in an attempt to buy another few vital hours or minutes.

Captain Bill Steer, whose family live in Williamstown, Rhondda Cynon Taf, was among the last to leave, and was mentioned in dispatches for his bravery.

His son-in-law, Kenneth Martin, said that he thought he'd left it too late to evacuate, and that he'd either die fighting or be taken prisoner.

"Bill was commanding a gun installation with the Royal Horse Artillery on the outskirts of Dunkirk. It was vital for them to keep firing to try and put off, for as long as possible, the German guns coming in range of the beach and massacring thousands of allied troops."

'Rowing'

"After nearly everyone else had left, Bill was given the order to spike the guns in order to stop the Germans using them, then make a run for it.

"Unfortunately his fellow officer ran off with their only motorbike, leaving Bill stranded, so he had to make a dash on foot for the beach, while the Germans poured into the town."

"He and a handful of others were pretty much the last people to make it off the beach alive, rowing away in a metal lifeboat!

"They were rescued by a Royal Navy destroyer half-way across the channel, and Bill wanted to go back to Dunkirk for more!"

"He'd never really talk about it while he was alive, I learnt all this from the men he led there.

"He never flinched at what he had to do, even though he'd seemingly given up realistic hope of getting out alive."