Peru's minorities battle racism

- Published

Peru may be a melting-pot nation, but it has deep-set racial prejudices

There is a saying in Peru - "el que no tiene de Inga tiene de Mandinga" - which means every Peruvian has either some indigenous or African blood.

It is an often-quoted proverb used to explain the country's blend of races.

Racial mixing began mixing with the Spanish conquistadors who overran the Inca Empire in the 16th Century, and continued with successive waves of African slaves, indentured Chinese labourers and migrants from Japan and Europe.

The phrase speaks of a melting-pot nation but does not hint at Peru's deep-set prejudices.

The country has socio-economic gaps along race lines and its inherent, if subtle, discrimination can mean an indigenous woman may only ever work as a maid; a black man may only ever aspire to be a hotel doorman.

This is the kind of everyday racism which dictates the lives of many Peruvians.

Reinforced stereotypes

Perhaps the biggest obstacle to ending this racism is the fact that it is simply seen as a joke.

Daniel Valenzuela foresees a day when Peru has a black president

Complain and people will chide you and ask: "Where's your sense of humour?"

And, by and large, most Peruvians don't complain; they just go along with it.

Racial stereotypes are reinforced on a daily basis in the media. Tabloid newspapers use crude sexual innuendo to describe a black congresswoman in a way they would not dare refer to a white member of parliament.

They compare a black footballer to a gorilla when he loses his temper on the pitch.

And on prime-time Saturday night television, the country's most popular comedy programme abounds with racial stereotypes with which the audience are so familiar they scarcely question what they are watching.

Temporary suspension

But in April, something changed.

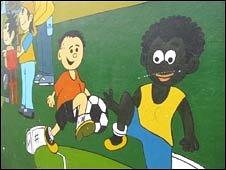

One of Peru's main channels, Frecuencia Latina, suspended a popular comedic character called El Negro Mama - a grotesque caricature of a black man, played by an actor wearing a prosthetic nose and lips with a blackened face.

The channel pulled the character after the threat of legal action from Lundu, an African-Peruvian civil rights organisation led by campaigner Monica Carrillo.

In a statement, the channel accepted the character may have been offensive to some viewers.

But it refused to suspend a stereotypical depiction of an indigenous Andean woman - La Paisana Jacinta - despite complaints of racism, saying the character had "evolved".

Racial stereotypes, however, die hard.

Ms Carrillo became the target of an abusive counter-campaign using social networking sites to call for El Negro Mama to be reinstated. And after little more than a month's absence, the character was back on the air by popular demand.

Frecuencia Latina declined the BBC's request for an interview.

Few options

Like many Peruvians, Daniel Garcia cannot see what all the fuss is about.

"Here in Peru we poke fun at all races," said the middle-class lawyer and father-of-three.

"I have black friends who laugh at El Negro Mama. I don't see the character and think all black people are like that; that they walk in a simian way, that they are thieves.

Peru was the region's first country to apologise for centuries of prejudice

"On the programme they also imitate two old white upper class women, but you don't see them going out onto the streets and protesting, because they understand that it's just TV.

"If you don't like it, you can change the channel!"

But for most black Peruvians, who make up around 10% of Peru's 29.5m population, there is little they can do to change their options.

The majority are trapped in poverty and lack opportunities: Indigenous and African-descendants in Peru earn 40% less than mixed-race people, says Hugo Nopo.

The co-author of Discrimination in Latin America: An Economic Perspective, he explains that this is a trend across Latin America.

Peru lies somewhere in the middle - better than Brazil but worse than Ecuador, for example - in terms of wage differences along race lines.

In El Carmen - one of the historic population centres of African-Peruvians, 180km south of Lima - Carmen Luz Medrano said that when she was at school, the teachers said "blacks" could only think until midday.

"I had to work twice as hard to get good marks," said Ms Medrano, who now works with children in El Carmen.

"The girls I teach can still get racist comments from the teachers, but now they're better prepared to respond.

"They're not the same submissive kids who used to bow their heads and take it as we did."

Dapper poet

But in tough Lima neighbourhoods like La Victoria, it is harder to shake off the racial stereotypes, said Cecilia Ramirez, director of the Peruvian Black Women's Development Centre.

"The hardest thing about being black in Peru is seeing how our children are discriminated against and how this affects their identity and their self-esteem to the point that they want to deny their own race," she said.

"Black is associated with all that's bad and negative."

African-Peruvians have much to be proud of. Their music and dance, food and religious festivals have left their mark on Peruvian culture.

African-Peruvians also took to a poetic style known as decima, a form which was exemplified in the work of Afro-Peruvian poet Nicomedes Santa Cruz.

Daniel Valenzuela demonstrated this form eloquently, articulating the verse's rhyme and meter.

A dapper young man wearing pinstripe trousers high on his waist, polished black shoes and a white cloth cap, he was optimistic about the future for ethnic minorities in Peru.

"The day will come when there's a black president in Peru - just like Obama in the US - and he's going to make some big changes," he said.

Change now

Last November, Peru became the first country in the region to apologise to its African-descended population for centuries of abuse, exclusion and discrimination.

Yet the country is considered one of the most backward nations in the Americas when it comes to legislation against racism, and promoting equal opportunities.

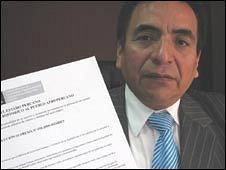

"In the fight against racial discrimination we've come up against certain limits," said Mayta Capac Alatrista, director of the Institute for the Development of Andean, Amazonian and Afro-Peruvian Peoples.

"It's difficult to sanction a particular media outlet... as it's difficult to identify who's at fault. A letter of complaint can often serve a moral sanction."

While Lundu and other Afro-Peruvians movements welcome the state apology they agree they cannot wait for the state to take concrete action.

"We can't wait for another generation. We need a change right now", said Ms Carrillo.