Ratings agencies to come under spotlight at hearing

- Published

The Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission has already held four hearings

There is a vital new piece of theatre coming to New York.

It might not draw the crowds of some of the big shows up on Broadway, nor will it match the glitz of their production, but it has a much bigger audience.

It also, arguably, has a more dramatic storyline, albeit one hidden within hours of dreary dialogue that many of the audience won't understand.

Congress's Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission comes to town for the fifth of its hearings into what caused the financial crisis.

This one looks at the role of the ratings agencies, the companies whose job is to rate the credit of firms, countries and investments.

'Screwed up spectacularly'

These agencies notoriously gave high ratings to the mortgage investments that investors were shovelling money into in the 2000s.

Given what happened to the housing market, and how many people defaulted on their mortgages, it is fair to say the agencies got their ratings horribly wrong.

This is hardly news. The facts of how the ratings agencies screwed up so spectacularly have been much rehearsed.

For example there is the small problem of their business model in which the same people who sold mortgage investments were also the ones paying to have them rated.

'Cast as the baddie'

So to some extent the script for the hearing is already known.

We can expect Raymond McDaniel, the boss of Moody's, to hear expressions of bemusement if not outrage that his business model was so obviously open to a conflict of interest. Plenty will declare themselves shocked, shocked that the ratings agencies could have operated in such a compromised fashion.

If so, the Moody's CEO won't be the first of the leaders of the financial services industry to find themselves cast as the baddie in this rolling theatre of blame.

One by one they have been turning up at the Commissions hearings all year to fulfill that role. Most famously, the head of Goldman Sachs, Lloyd Blankfein, found himself at odds with the Commission chairman Phil Angelides over Goldman's role as a market maker.

Mr Angelides seemed to be shocked that while selling mortgage backed securities to its client it was also betting some of its own money on a collapse in the housing market.

While Mr Blankfein pointed out that this is what market makers do, Mr Angelides likened Goldman to someone selling a car with faulty brakes and then buying an insurance policy on the buyer of those cars.

In an economy that fiercely avows the principal of free transparent markets, their exchange was immediately portrayed as the revelation of a rather murky detail of how finance actually works.

Billionaire patriot

Along with Moody's boss, for this week's performance the Commission has lined up a bona fide star with none other than Warren Buffett is slated to appear.

Mr Buffett, is the avuncular genius of the American markets who famously likened derivatives to financial weapons of mass destruction years before they did indeed cause, well, mass destruction.

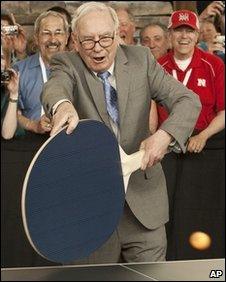

Warren Buffett is expected to try and bat away criticism

A tycoon investor often appears on the television business channels as a nice, billionaire patriot, talking about his long term bets on America and its economy.

His appearance this week gives just a hint that even if the lines have been heard before, the commission is determined that its hearings will spell out again the unpleasant realities of the US financial system.

Because nice Uncle Warren isn't talking voluntarily. The Commission had to use its legal authority to compel Mr Buffet to testify.

As many have pointed out, Mr Buffett may seem and may be a genial upstanding figure, but he is also a big player in all kinds of financial businesses which played their part in trashing the US economy.

Take those weapons of mass destruction he famously warned of.

As a large shareholder in Goldman Sachs, Mr Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway has done very well from Goldman's lucrative derivatives trading. And the ratings agencies that are the subject of this week's hearing? Well, he owns a large chunk of that business too, with a 13% stake in Moody's according to the latest reports.

Blame game

So if they choose to watch the Commission this week, Americans will again get a clear illustration of some distasteful facts of their financial system and of how it failed. Not just failed, many will argue, but actually ripped them off, pitching the economy into its worst recession in 75 years, throwing millions of them out of their homes and out of work.

But there is the problem. Even if they do watch there is a real danger that hardly anyone will understand. Levels of financial literacy among the general population are worryingly low. In 2009 the FINRA investor education foundation embarked on extensive research seeking to answer the question, "how financially capable are Americans?"

The answer takes up many pages but can be boiled down to: "not very."

For those with a thirst for detail, consider the fact that fewer than half of FINRA's respondents were able to give the correct answer to basic questions about inflation and interest rates. In the light of that it is hardly surprising that the commission has felt the need to lead its audience and its peevish witnesses along some well trodden paths through the financial crisis.

People being unable to pay home loans contributed heavily to the financial crisis.

What the commission has not yet done though is to drag its audience onto the witness stand. Perhaps it should. Before ratings agencies could give such hopelessly inaccurate ratings to the bad mortgage bonds that investment banks were selling, many Americans had to be taking out mortgages they could not afford, and probably could not understand in the first place.

If, as most people accept, the financial crisis started in the US housing market, then many American home-buyers share some of the blame for the crisis that unfolded. That is perhaps the most uncomfortable of the many unpalatable truths about which the commission will eventually report.

'Bankrupting consequences'

HL Mencken famously described democracy as "the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard."

The financial services of the US are not a democracy but operating within one, and they seem to have fulfilled that theory.

The common man and woman wanted cheap loans. They got them good and hard. Mr Angelides and the Commission certainly know this and maybe that is a piece of the drama they do not want to act out.

After all what metaphor of car sales could he use for the public? Well, maybe they could compare demanding more cheap loans, without considering their full bankrupting consequences, to someone who insists that they be able to buy a car, without paying attention to the calamitous effect the relentless pursuit of oil might have on the environment.

Oh wait: that is another inquiry into another disaster.