From ice cream men to 'enemy aliens'

- Published

Exactly 70 years ago the lives of thousands of people living in the UK were sent into turmoil by events hundreds of miles away.

On 10 June 1940 Benito Mussolini declared war on Britain.

Shortly afterwards, all Italian immigrant men over the age of 16 were declared "enemy aliens" and rounded up for internment.

Under Regulation 18b of the Emergency Powers Bill the arrest was permitted of any person, irrespective of nationality, who might be a security risk in time of war.

The catch-all nature of the law meant few Italian families were untouched.

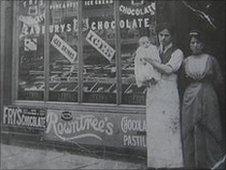

Suddenly people who had been at the heart of their community, often in ice cream or fish and chip shops, were heading to camps on the Isle of Man or further afield.

Many of their businesses became the target of attacks on that June night.

A crowd of several hundred people gathered outside the Empire Cafe in Annan, Dumfries and Galloway, owned by the Toni family.

A brick was thrown through the shop window and police and the town's provost had to appeal for calm.

The local newspaper reported: "He pointed out that though we were fighting Italy we did not make war on women and children and there were women and children in the building."

The group eventually dispersed about midnight and no further damage was done.

The writer, Joe Pieri, recalls similar scenes in Glasgow in his book River of Memory.

His family owned the Savoy Cafe at the corner of Renfrew Street and Hope Street.

Some Italian shops were a target for attacks after Mussolini declared war

He recalled: "A crowd of about 100 shouting and gesticulating hooligans, pushing in front of them a handcart loaded with stones and bricks were gathering in front of the shop.

"'There's a Tally place ... do it in!', came the shout, and a barrage of missiles came flying through the air, smashing into the glass frontage of the shop."

The front door was broken down and the property looted before the crowd eventually moved on.

Antony Visocchi, who now lives in New Jersey, said the same thing happened to his family in Fife.

He told the BBC Scotland news website: "My father was a British subject and was not interned but that did not stop a mob from smashing the plate glass windows of his cafe in Leven."

Many towns, of course, did not see such a violent reaction to the announcement but the prominence of many Italian businesses made them an easy target for any unrest.

At the same time, the arrests and internments began.

Pierpaolo Pacitti from Glasgow said: "My father Alberto was interned for four years, firstly in Barlinnie, then Brixton and York before being imprisoned at Peel on the Isle of Man

"He was Secretary of the Fascio (fascist group) in Park Circus at the time of his arrest, the day after his father, along with my mother's father, were arrested.

"Ironically, the arresting police sergeant and his colleagues were frequent visitors to the 'back shop' of the family cafe in George Street."

Brian Steel from Cupar said his grandfather owned and later worked as an employee at shops in the Hilltown area of Dundee.

He said: "On hearing the news that Italy declared war on the radio, my grandfather announced to the family that the police would be coming for him.

"They arrived shortly afterwards and he was taken to the Isle of Man.

"My mother described him as being a hefty man when he left and as being very thin on his return from internment."

Hundreds killed

It was only a matter of weeks after the internments began that a tragedy claimed the lives of many of those who had been arrested.

On 2 July 1940 the Arandora Star, a converted passenger liner, was en route from Liverpool to a camp in Canada when it was struck by a torpedo from a German U-boat.

It resulted in the death of more than 400 Italians on board.

Alvaro Rossi from Newburgh in Fife said: "My great uncle Silvio da Prato was drowned as a result of the sinking of the Arandora Star.

Many Italians ended up on the Arandora Star like these survivors

"According to some who survived he decided to go back to his cabin to collect something, and that was the last they saw of him."

Those events have echoed to this day.

Dr Philip Cooke, of Strathclyde University's School of Humanities, said the Arandora Star had a "lasting effect".

He said: "Outwardly the Italian community has managed to incorporate the disaster into the wider history of the Second World War and of the Italians in the UK.

"Inwardly, in family memories above all, I suspect things are rather different, and there is still a lot of unresolved grief many years after the event."

An appeal is ongoing to create the world's largest memorial to the victims in Glasgow.

It is intended that all of the Scottish Italians who lost their lives should be commemorated.

Rightly proud

By 1943, Italy's war with the Allies was effectively over and the internees began to return to the families and businesses they had left behind.

Nowadays it is hard to think of a British town or village which does not have its Italian shop or cafe.

Britain is proud of the achievements of Lawrence Dallaglio, Paolo Nutini, Joe Calzaghe and countless others descended from those first immigrants.

The Italian community has become an integral part of the national identity.

Yet, it was only seven decades ago that those bonds risked being torn apart forever.

- Published10 June 2010

- Published10 June 2010