Mars500: Just like the real thing?

- Published

The crew want to book their place in the history of space exploration

There was all the pageantry of a real space launch.

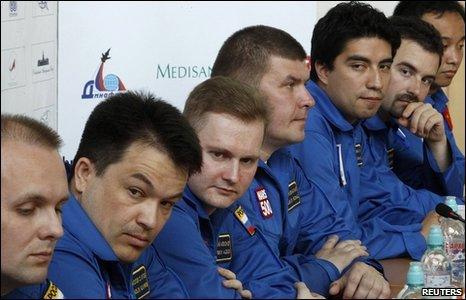

The six "astronauts" wearing bright blue jump-suits and even surgical masks, were paraded before banks of television cameras and hordes of journalists at a news conference before entering their mock spaceship.

Amongst the long rows of VIPs at the news conference were senior officials from the United States, China and the European Union.

If, as some experts believe, the main aim of the Mars 500 experiment is to publicise the concept of human flight to the red planet, then it has surely succeeded beyond all expectations.

"I am very happy to be part of this project," said Diego Urbina, the Colombian-Italian and most extrovert member of the crew.

"It will raise awareness of space flight so hopefully a few years from now there will be a real flight to Mars."

He confessed that Elton John had been his inspiration.

"I don't know if you know that song Rocket Man," he asked.

"I want a future like that… where people will be going frequently into space and will be working there and it will be very usual."

The facility contains living quarters, a gym and sauna

In front of the world's media, all the team spoke confidently about the chances of the experiment being successful - in other words that noone would crack under the stress of such lengthy confinement in such claustrophobic and bizarre conditions and demand to be let out.

"The target is for all six of us to be here for 520 days," said the French crew-member Romain Charles who took a guitar with him into the cluster of brown and silver-coloured metal tubes which will be home until November 2011.

After the news conference, the six crew disappeared, re-emerging an hour later by the entrance hatch to the mock spaceship, where they put on another high-spirited performance for the media.

Finally, blowing kisses and waving to wives, girlfriends and relatives, they walked up the steps and through the entrance hatch.

A solemn-faced official slowly closed and sealed it behind them.

So now reality bites for the six-member volunteer crew.

What will they be thinking as they sit inside their tin cans in north-west Moscow where outside the warm sun shines and the flowers blossom?

There is no thrill of a blast-off and flight through space.

There are no windows from which to watch the Earth gradually shrink away.

And no anticipation of reaching a new world more than fifty million kilometres away.

Instead, silent inertia, stale air and tinned food.

And everywhere cameras watching their every move, looking out for signs of mental collapse.

They have just one thing to cling on to, that they are playing their part in the history of space exploration.

That their success in this experiment will mean a human flight to Mars is a step closer.

And space experts already believe the first flight could be just 25 years away or even less if there is the political and economic will from countries with advanced space programmes.

- Published3 June 2010