What now in Afghanistan's crucial year?

- Published

In a vital year for Afghanistan, the BBC's Lyse Doucet talks to the commander of international forces and a former senior Taliban official on how to tackle the insurgency.

In a telling coincidence, at the moment a call for talks with insurgent groups emerged from a national peace jirga, news came that the senior Taliban commander in Kandahar city, Mullah Zergay, had been killed.

"I think it's a remarkably unified message," said the commander of Nato-led forces, Gen Stanley McChrystal, in a BBC interview.

"I think it shows strength on the part of the government of Afghanistan, in their desire and commitment to protect the Afghan people, and at the same time a sense of generosity and unity to offer those insurgents the opportunity if they are willing to come forward to be part of society."

A former senior Taliban official, Abdul Salaam Zaeef, who lives under government protection in Kabul, welcomed the call for talks "from the people of Afghanistan".

But he repeated the call made regularly by the Taliban - there can be no talks while foreign forces are in Afghanistan.

"This is not possible for Americans to say first we should kill them, after that we should talk to them. The Taliban are not a people to be defeated," he told the BBC.

Gen McChrystal called it a "strange message" from the Taliban when they attacked the peace jirga tent during the opening ceremony last Wednesday.

"That shows me the contradictions in their actions and in their message," he said.

He hailed Afghan government resolve, but his comments were soon eclipsed by the sudden news that two key members of President Karzai's security team had resigned over the peace jirga attacks.

The departure of the intelligence chief, Amrullah Saleh, and Interior Minister Haneef Atmar is also the result of long-standing strains with the president as well as differences over the new outreach to the Taliban.

It fuels new concern about the months ahead.

Decisive battle?

There is much discussion in international circles of the "narrative" that should run through a crucial year - which includes a series of choreographed events from the London Conference in January, the just-concluded peace jirga, the international Kabul Conference in July, and then parliamentary elections in September.

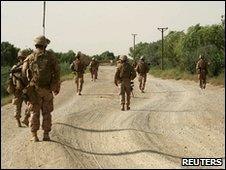

There is another calendar for foreign and Afghan forces engaged in the biggest offensive against the Taliban since the movement was toppled in 2001.

Now that the peace jirga is over, the focus will shift to what is expected to be mounting pressure on the Taliban in Kandahar province, including Kandahar city.

The area, called the spiritual home of the Taliban, is vital in symbolic and strategic terms.

Gen McChrystal rebuffed a widely held view that Kandahar was the decisive battle in an Afghan mission now under pressure to show results before President Barack Obama's July 2011 deadline to start pulling out some troops.

"I studied military history and you almost never know until after the fact what turned out to be the decisive point, so I certainly wouldn't predict it in advance. But I will say I think it's very important," he said.

I pointed out that Afghans have an old saying: "When you have Kandahar, you have Afghanistan."

He agreed: "I think that's exactly right, when we get Kandahar, it's a great step towards success in Afghanistan and it shows the resolve and capacity on the part of the government."

The top US general dismissed a growing perception that results on the ground in the town of Marjah in neighbouring Helmand province were a cautionary tale.

When Nato and Afghan forces went into combat in February, they predicted they would have the situation in hand in a few months. It was hailed as the opening salvo in a year to "turn the tide".

But reports from Marjah speak of continuing Taliban intimidation, and a less than stellar performance from Afghan police and an embryonic civil administration.

Gen McChrystal had called it a "government in a box" that would move in once US-led Nato forces and Afghans prevailed in Operation Moshtarak, or "together".

"No war goes like you would like it to go. But we have seen significant progress," he insisted, pointing out schools and bazaars were now open.

He said neither he nor I could have walked the streets of Marjah in February, but it was possible now.

"Some things go faster, some slower… but I don't feel in trouble."

Asked about his greatest fear regarding the Kandahar campaign, Gen McChrystal replied: "I think it is probably expectations".

He listed a daunting set of goals, including improving security inside Kandahar city, Afghan police partnering with coalition forces, several rings of security outside the city, increased governance including municipal and provincial government capacity and bringing in an inclusive structure.

All this would be done while carrying out security operations to protect the people against Taliban attacks.

"Orchestrating that is the complex part. It's not impossible but it won't come out perfectly. Afghans won't feel it every day but as months pass there will be an increasing sense of a better future," he said.

Overall goal?

There is much apprehension, if not scepticism, about the upcoming operations in Kandahar, Afghanistan's second largest city with some 850,000 people.

Military chiefs say the Kandahar operation will be different to Helmand

It is regarded as the most difficult of terrain, where the Taliban have been digging in and threatening residents in advance of the expected operations.

Nato forces have been active for months in the districts around Kandahar city. They have taken pains to insist it will not be a military assault of the kind carried out in Helmand. It is described as a "process" of squeezing the Taliban rather than driving them out.

Gen McChrystal's aides call it "a rising tide rather than a crashing wave".

Abdul Salaam Zaeef warned the mission was doomed to fail. "When you kill 10 people in any village, you create 100 more enemies."

I asked the general, who has now headed his command for one year, about his overall goal.

Drawing on military history, he said it was not about killing the Taliban. "Defeating an enemy is defeating him from accomplishing his mission," he said.

"When we secure any part of Afghanistan, we deny the Taliban the opportunity to be successful. At the end of the day that's what it takes to defeat the Taliban."