How will the new Office for Budget Responsibility work?

- Published

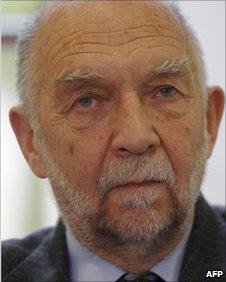

Sir Alan Budd is casting a sceptical eye over recent official economic forecasts

Since the new, independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) was announced by the coalition government last month, many people have been wondering exactly how it will work.

"We have changed the way Budgets are written, by establishing a new Office for Budget Responsibility, which will stop any chancellor fiddling the figures ever again in our history."

Tough words from David Cameron in the Queen's Speech. The new OBR does not sound like a political bombshell. But it is key to the government's strategy to repair the public finances.

So how will it work? Rachel Lomax, once a top Treasury civil servant and then deputy governor of the Bank of England, says that it is partly about "explaining where the numbers come from".

But it is also, she says, about making sure the public spending numbers are based on "economic assumptions that people would accept as reasonable".

Critical eye

Already, the OBR's new head, Sir Alan Budd, is running a sceptical rule over the economic forecasts of the last government.

If the OBR is to make its mark, it needs to establish its independence in the eyes of the public and of politicians. That may mean a row with the chancellor.

When the new chancellor, George Osborne, was in opposition, he made some bold claims for the OBR - but he also sounded distinctly nervous. He thanked Sir Alan Budd for agreeing to chair the OBR in its first year.

"Whether I thank him again in a couple of years' time is another matter," he joked, "but that is the whole point."

Mr Osborne may worry that the OBR will challenge his authority. Others worry that it will not be challenging enough.

Lots of people see it as the new government's version of Labour's decision in 1997 to give independence to the Bank of England. But the Bank is different. It is 300 years old - and setting interest rates is not a job that parliament ever really controlled.

Taxing and spending are different. They are at the heart of what governments do.

"We've had civil wars about that sort of thing," says Rachel Lomax. "Colonies have declared independence." Taxing and spending, she adds, cannot just be outsourced to a technocratic quango.

The OBR needs to be independent of ministers - and it needs to avoid being captured by the Treasury.

Michael Cockerell has spent decades making documentaries on the inner workings of Whitehall. He thinks the OBR's very name sounds like an attack on the Treasury.

"When you set up a new body and call it the Office for Budget Responsibility," he argues, "it is implied that the Treasury was the Office for Budget Irresponsibility."

'Weak Westminster'

Many of the new Office's staff come from the Treasury, but the Treasury may see the OBR as a way to help curb overspending chancellors.

Mr Cockerell says Sir Alan Budd is just the right sort of person to put distance between the Office and the mandarins because "Alan Budd is nobody's creature".

What about relations with parliament? Lots of other countries are trying to curb government overspending - often by strengthening parliament's role.

Rachel Lomax welcomes the OBR's remit to check the Treasury's figures

Joachim Wehner of the London School of Economics is scathing about Westminster's failure to curb public spending.

"The British parliament really came about because it demanded control of public finances," he points out. "It once played a fairly important role in budgetary decisions, but it no longer does."

Westminster, he believes, is now seen as "the epitome of weakness".

Ouch. But Diane Abbott, candidate for the Labour leadership and former member of the House of Commons Treasury Committee, is right behind him.

The committee's chair and its members were appointed by party whips. "They largely appointed people who wouldn't give them any trouble, and who weren't interested in the subject," she says.

That may start to change as MPs in the new parliament elect chairs of committees directly.

The OBR might also be particularly useful to a coalition, as an independent check on fiscal numbers.

"Countries that tend to exaggerate their budget figures are one-party governments," says Mark Hallerberg, a professor at the Hertie School of Government in Berlin.

"They hope to do better in the next election, and it's quite clear who benefits," he adds.

Future generations

With coalition governments, there should be less incentive to cheat.

So the new OBR may, if all goes well, make parliament stronger and also glue the coalition together. But does it matter that an unelected body has such power?

Democracies are bad at representing the interests of future generations - the unborn do not vote, but will have to pay off the national debt if we do not do so today The OBR may help to protect them. If that is undemocratic, perhaps democracy itself has failed.

Rachel Lomax puts the boot in: "If you've got politicians that you can't trust to take decisions about something as fundamental as the state's right to confiscate your property and spend it on someone else, you've got a problem with your politics."

You can hear Frances Cairncross's Analysis programme on BBC Radio 4 on Sunday, 13 June at 2130 BST or download the podcast.