Africa’s brewing firms try to compete with moonshine

- Published

Sorghum can be used to make beer

Every year, countless numbers of Africans risk their health and their lives drinking illegal alcohol.

The "informal" brewing market in Africa is worth an estimated $3bn (£2.1bn) a year.

Now some of the continent's biggest brewing firms are trying to break into this vast potential market by developing safe and affordable alternatives, but they are facing opposition.

With names like "Kill me quick", "The dog that bites" and "Goodbye Mum", African moonshine has a frightening reputation.

Over the years, thousands of Africans have been killed, blinded or rendered sterile by drinking these lethal concoctions.

Market gap

In one of the worst recorded cases nine years ago, 128 Kenyans died and a further 400 were harmed after drinking a particularly poisonous batch of illicit booze.

One of those who lost her life was the landlady of the Nairobi bar where the substance was being sold.

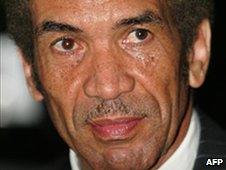

Popular Ugandan DJ Ronnie Sempangi died last September

Last September, one of Uganda's most popular media personalities, DJ Ronnie Sempangi, collapsed and died after drinking a brew laced with pure methanol.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) says that about half of all the alcohol drunk in sub-Saharan Africa is produced illegally, with 85% of consumption in Kenya and 90% in Tanzania coming from the "unrecorded" market.

Barley, the essential ingredient in beer, is still not grown in many parts of Africa. High taxes and poor supply chains have also pushed up the price of legitimate goods. Toxic homebrew plugs the gap in the market.

Africa's booming cottage industry is made up of clandestine breweries, where maize and sorghum is fermented, using water that itself is often filthy.

The alcohol content is bolstered, using anything from embalming fluid to stolen jet fuel.

The resulting grog may sell for as little as 20 US cents a glass.

But for the poorest Africans, living on a couple of dollars a day, it is often the only way of blotting out their troubles.

Alternative ways

Brewers, alongside mining groups, rank among the biggest multi-national firms operating in the continent.

Botswana's President Ian Khama backs higher taxes

Most would like to develop low-cost commercial alternatives to this illegal fare.

Despite Uganda being one of Africa's poorest countries, the UN states that the country has the highest per-capita consumption of alcohol anywhere in the world, outstripping even the beer-swilling Czechs.

East African Breweries, home to the Tusker and Pilsner brands, wants to tap into that demand.

It has lobbied the Kenyan government successfully for tax breaks to develop new products.

It has even partnered up with Equity Bank, Kenya's largest customer-based bank, to distribute loans to farmers at a 10% interest rate to help them grow sorghum crops and become suppliers for sorghum beer.

Opposition

SAB Miller, the biggest brewing firm in the SADC zone, is trialling the production of beer made from locally-grown cassava fruit at a new facility in Swaziland.

The production process has not been without difficulties, as cassava starts to rot within three days of harvesting. But the end product could be a healthier, affordable alternative.

SAB Miller hopes to develop affordable brands

The brewers, however, have met opposition from health campaigners and even some politicians.

After taking office in April 2008, Botswana's famously teetotal president, Ian Khama, lobbied for tax on alcohol to rise, to as much as 70%.

The Sandhurst-educated Mr Khama said that he wanted to combat the effect of excessive drinking on Setswana society, saying: "No responsible government... can afford to turn a blind eye to the circumstances."

But faced with loud opposition from the brewers and Botswana's hospitality and tourism industry, he compromised at just 30%.

'Basic right'

There is little doubt over the part that alcohol plays in Africa's problems.

One recent academic study in South Africa suggested that alcohol was a contributory factor in 76% of all violent deaths in the country and almost half of all deaths in Soweto alone.

The WHO has clearly linked the spread of HIV/AIDS in Africa to alcohol misuse. It says infrequent heavy drinking by men is the biggest problem.

About 40% of African women abstain from alcohol altogether, rising to 70% in Muslim areas of Nigeria, Sudan and Ethiopia.

The WHO aims to promote health education and moderate taxes to discourage the binge-drinking that typifies weekend life in many African towns and cities.

But it has a fight on its hands. Unlike in the Middle East or parts of Asia, ordinary Africans view access to alcohol, regardless of income, as a basic right.

The legitimate brewing industry may claim that unless safer alternatives are developed soon, the death toll from Africa's deadly hooch industry can only rise further.

Watch Africa Business Report on BBC World News on Saturday, 19 June at 0130 GMT and 2230 GMT and on Sunday, 20 June at 1330 GMT and 2030 GMT