Fourth Iran sanctions: Last resort or lost opportunity?

- Published

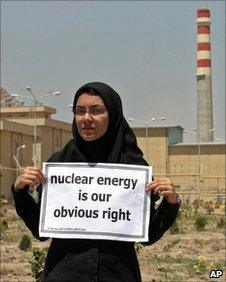

Iran says its nuclear ambitions are peaceful

For months, the US has been trying to build the maximum international unity for sanctions against Iran.

The importance of the UN resolution was "less the specific content than the isolation of Iran by the rest of the world", the US Defence Secretary Robert Gates said in April.

After patient and persistent diplomacy and a few perks, Russia and China, Iran's powerful trading partners, finally fell into line.

But divisions have emerged elsewhere in the Security Council, signifying concerns about a strategy that appears to stress pressure over engagement with Iran.

The five permanent members of the Security Council - the US, Britain, France, China and Russia - plus Germany (the so-called P5+1) fear Iran is trying to build a nuclear weapon.

They point to its continuing defiance of UN resolutions, demanding it end enrichment of uranium and non-co-operation with the UN atomic agency.

They call their strategy a combination of diplomacy and pressure, aimed at convincing the Iranians they are heading in the wrong direction.

The sanctions are meant to "persuade Iran to halt its nuclear programme and negotiate constructively and in earnest with the international community", America's UN ambassador Susan Rice told reporters on Tuesday, a day before the vote on the draft resolution.

Dismissed deal

Security Council members Turkey and Brazil said they had negotiated constructively with Iran, recently reaching a nuclear fuel agreement they believed could serve as a basis for a more comprehensive dialogue with the P5+1.

But the Americans dismissed the deal as an Iranian manoeuvre and instead tabled the new sanctions resolution, the fourth in as many years.

Brazil and Turkey voted against the draft.

The opposition of these two powerful emerging states could not stop the resolution, but will it weaken America's attempts to build an effective international front against Tehran?

University of Notre Dame sanctions expert George Lopez says no - not if the US has the support of two traditional allies of the Islamic republic.

"In February and March there were many questioning whether China and Russia were on board, and felt that virtually no sanctions package of any significance would come forth, when quite the opposite has happened," he says.

"There have been some concessions, but the Chinese and Russians are more strongly backing this than many would have assumed in February and March," he said.

'Opportunity lost'

Others, though, believe the deal brokered by Turkey and Brazil offered a real alternative to a sanctions policy that has not worked.

Recently a group of US experts - including non-proliferation specialists and former top diplomats - issued a statement urging the Obama administration to consider the Tehran deal.

While noting its shortcomings, they said if enacted it would "represent a first step in halting Iran's progress towards nuclear weapons capability".

Iran denies it is building a bomb, insisting that its nuclear programme is for peaceful purposes.

But it has also made its right to nuclear energy an issue of national sovereignty, and a rallying call against the West.

Sanctions will not change that, says Gary Sick, a former member of the US National Security Council. Diplomacy might have.

"To have Brazil and Turkey actively working to develop a different approach to Iran's nuclear situation was a huge advantage for the US," says Mr Sick.

"Having two mid-level powers that Iran trusted could be invaluable in making further progress, and I think that was a huge opportunity that was lost."

For some here the steady drum beat of sanctions and the divisions in the Security Council raise the spectre of Iraq, which ended in war. We may be a long way from that.

But the question is crucial: Will sanctions drive Iran back to the negotiating table, as the P5+1 claim? Or will they end all possibility of talks, as Turkey, Brazil and others fear?

And if so, what then?