Keydata: why were investors sold "death" bonds?

- Published

Last year, investment firm Keydata was closed down by the Financial Services Authority for breaking tax rules and because it was insolvent.

The BBC has been investigating why £450m belonging to 30,000 UK investors is at risk.

Having asked "Where did the money go?" , we take a closer look at Keydata's business and the kind of investments it was selling.

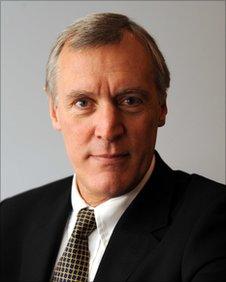

Matthew Bullock has offered loans to help some N&P customers

One curiosity of the Keydata affair is the nature of the assets in which the customers' money was invested.

The promised return on their Keydata policies, dubbed by some as "death" bonds, was going to be generated by portfolios of second-hand US life insurance polices, owned by the companies SLS and Lifemark in Luxembourg.

The buying and selling of second-hand life insurance policies does not exist in the UK but is known in the US as the "life settlements" market.

The idea is that the policies will generate a stream of income as the people originally insured under them die, and the insurance companies then pay up.

Some of the Keydata marketing literature published in 2005 failed to make this clear, just as it failed to make clear that investors money would be invested in Luxembourg.

Other claims made by Keydata at the time were simply false.

"I was told the product had been set up by KPMG; HSBC were supposedly involved and to me both of those brands gave a lot of assurance," says Peter Magowan, an organiser of the Keydata victims action group.

Both KPMG and HSBC have described Keydata's use of their names as "misleading and inaccurate" and told Keydata to remove the references from its literature.

A spokesman for Stewart Ford, the boss of Keydata, said his firm had simply repeated claims from marketing literature prepared by a previous distributor of the SLS bonds, and on enquiry had been told the claims were accurate.

'Difficult position'

The Keydata affair has embarrassed one of the UK's biggest building societies, the Norwich & Peterborough.

From 2005 onwards its financial advisors in its branches sold Keydata polices to some 3,500 of its customers.

The society has denied any liability for its customers' losses but has expressed great sympathy.

Two weeks ago it offered to make an interest free loan to 1,900 of them, possibly amounting to £2m, to tide them over to the end of the year.

"We are owned by our customers and some of them are clearly in a very difficult position as they need the income to meet their monthly outgoings," said Matthew Bullock, the N&P's chief executive.

'Unusual asset class'

The N&P says it prompted Keydata to improve the quality of its marketing literature.

The brochure for Keydata's policies was much improved by 2008

By 2008 the Keydata brochures used by the society were making it explicit that the investments would be in second-hand life insurance polices via the Lifemark investment management company in Luxembourg.

They also highlighted strongly the risk of the expected interest payments not appearing, or even of the capital being lost.

"We asked them to elaborate on the risks," said Mr Bullock.

But why did N&P sell the policies in the first place?

Was a portfolio of second-hand life insurance policies really a suitable investment for elderly people seeking a safe home for their pension nest eggs?

Mr Bullock says they were, because they offered a high level of income which his customers wanted.

"There is nothing wrong with the product; it is an unusual asset class, not related to the financial markets," he said.

"It was an attractive product and we carried out exhaustive due diligence. [The problem] is not to do with the product but the management.

"We do not yet understand what went wrong and we wait for the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) and administrators' reports," he added.

Independent advice

Keydata's policies were mainly sold by independent financial advisers.

Colin Leaver, a retired business executive in Bishop's Stortford, invested £48,000 in his policy in 2006 on the advice of a firm called Rockingham Retirement, which sold Keydata polices to about 55 clients.

At Colin's request Rockingham's chief executive and another director went to his home to assure him the investment was suitable and safe.

"I thought I'd done the correct sort of homework to satisfy myself that the money invested would ultimately come back - I'd get a small pension fund running over a number of years before the capital matured," Colin says.

"Until January 2010 I was receiving monthly interest payments on that capital as part of that pension arrangement but they have stopped until this whole thing is sorted out," he says.

"I feel embarrassed that it has happened as I'm a fairly logical bloke and I worked out that this was probably the right way to go instead of buying an annuity," he adds.

Regulated

What does Rockingham make of all this now?

Its chief executive Gary Forster says the underlying idea of investing in death bonds, such as those sold by Lifemark, was entirely sound.

"There are firm guarantees associated with these life insurance policies - they have never failed to pay out when someone has died," he says.

"In principle, if well managed, they are guaranteed to pay out - lots of other funds [of this type] are paying supremely well."

Mr Forster points out that Keydata was regulated by the FSA, the Lifemark funds were audited, and Rockingham had checked the existence of the underlying life insurance policies.

He thinks Lifemark, of which Keydata founder Stewart Ford was also a director, must have managed its business very badly.

According to some of Keydata's policy documents, about 30% of the cash handed over by investors was supposed to be put aside.

This was to cover administration costs, fees, expenses, short-term interest and capital repayments to customers, and the future cost of renewed premiums to keep the valuable life insurance polices in force.

"The management of the Keydata funds was appalling," Gary Forster says, "it should have kept enough cash [to keep the polices in force]."

So why didn't it?

Ill-judged

Jack Irvine, a representative for Keydata's boss Stewart Ford, says that in April last year, the firm had "substantial" amounts of cash.

But it started "eating into its short-term cash reserves" to snap up more cheap, second-hand, life insurance polices in the USA, he said.

Just as it was about to raise more cash from investors, and keep the whole show on the road, the FSA closed down Keydata, with similar action taken by Lifemark's regulator in Luxembourg.

"Therefore Lifemark's current liquidity problems are the direct result of the ill-judged intervention of the regulators who failed to understand how this asset class work," says Mr Irvine.

He says Lifemark was not a "Ponzi" scheme, adding Lifemark has life settlement policies with a face worth of some $1.5bn to its name, which will eventually mature.

"All bond holders would have continued to receive the payments to which they were entitled on time as promised," Mr Irvine adds.

Still waiting

The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) has so far given £42m to just over 4,000 investors in the SLS policies.

There are more SLS claims in the pipeline, though 450 have also been rejected.

That still leaves the SLS investors with a huge collective shortfall of about £61m, which can only be improved if the administrators are able to recover money from any assets.

So far only limited compensation has been made available to a minority of the Lifemark investors.

Although 4,400 of them have had their Isa-related income tax bills paid by the FSCS, no decision has yet been taken about potential losses on their underlying investments.

"At the moment it's not clear what the implications are for these investors," said an FSCS spokeswoman.

"We also have to decide if Keydata was responsible for any other losses [of Lifemark investors]."

In Bishop's Stortford, Colin Leaver fears that other Keydata investors are in a far worse position than him.

"They are worse off than me, they are older than me and my wife, [they are] pensioners in their early and mid 80s and suddenly they've put all this money into these schemes and now they have no income coming in at all," he says.

What would the investors like to see now?

"I'd like the administrators to instigate legal proceedings based on the evidence they have got," Peter Magowan says.

"One year on and I'm sitting with no clear path to the restitution of my money."

- Published16 June 2010

- Published21 May 2010