Q&A: Why estimates of the BP oil spill keep changing

- Published

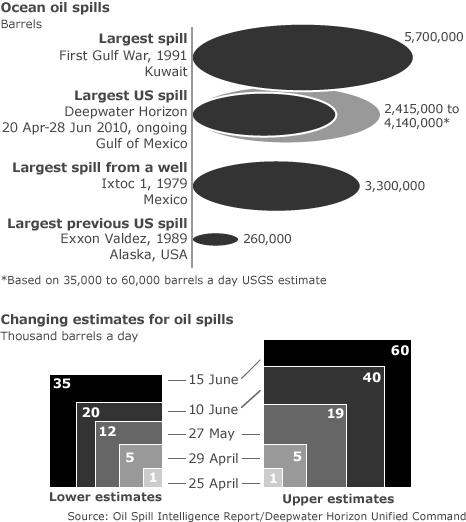

Estimates of the amount of oil escaping from BP's damaged well in the Gulf of Mexico have risen 60-fold since the disaster unfolded on 20 April. So why have the calculations varied so much and how is the spill measured?

Just how sharply have the estimates changed?

US scientists issued a figure of 35,000-60,000 barrels (1.5-2.5 million gallons) per day on 15 June.

The figure was accepted by US Energy Secretary Steven Chu as "a significant step forward in our effort to put a number on the oil".

By contrast, an estimate announced by US officials on 26 April put the flow at just 1,000 barrels per day. That figure was later revised to 5,000 barrels. Then it was 12,000-19,000, then 20,000-40,000.

Why does the flow rate keep rising?

Normally the flow from a well is measured on a rig but the flow meters on the Deepwater Horizon were destroyed along with the rig in the explosion.

The 15 June estimate is based partially on data gathered from pressure meters placed on the sea-bed on BP's containment cap, which is collecting some of the oil.

Another method scientists have used to measure the flow is to combine data from satellite photos of the slick on the sea surface with estimates of the oil's thickness. But the reliability of this approach depends partly on how much oil has reached the surface, says Geoffrey Maitland, professor of energy engineering at Imperial College, London.

Experts in fluid mechanics have been tracking particles coming out of the broken riser pipe and measuring their velocity. They have been refining their models of the flow based on the levels of oil, gas and solid particles coming from the well.

Other estimates are based on video from the downhole of the well.

A team from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US is also using acoustic techniques to measure flow rates.

How much oil is being collected by BP?

BP says the containment cap (the lower marine riser package, or LMRP) it placed on the well's damaged blowout preventer (BOP) on 3 June is collecting about 15,000 barrels a day, piping it up to a ship on the surface. Even if the amount of oil escaping is the low-end figure of 35,000 barrels, that leaves 20,000 leaking into the sea daily.

The British company was due, as of mid-June, to start up a second containment system (SCS) that would increase collection to 20,000-28,000 barrels a day.

The SCS is meant to take oil and gas from the BOP's choke line through a separate riser pipe to another vessel on the surface, where the fuels will be burnt off.

The company plans to be able to handle 80,000 barrels of escaped oil per day by mid-July.

BP "under-estimated the flow rate" and "over-estimated their ability to fight against that flow rate", says Ian MacDonald, professor of oceanography at Florida State University.

He told the BBC: "This was perhaps a fatal miscalculation... with the result that this crisis has continued much longer, with much greater release of oil than would have been necessary had they [BP] made much more accurate flow rates at the very start."

How accurate are the latest measurements?

It is very difficult to say because the models are constantly being revised and combined with observation.

The main plume of oil is being treated with dispersants and surfactants, wetting agents which lower the surface tension of the oil so it can mix with the water. These make an emulsion which brings the oil more quickly to the surface, where it can be scooped up by collection vessels.

There are concerns that some of the oil is forming separate, smaller plumes below the surface, Professor Maitland says. This may make it more difficult to estimate the total size of the spill.

Not all the oil has surfaced yet, but it will eventually, because oil is lighter than water.

The uncertainty in measuring the total size of the spill is harming BP, Professor Maitland warns.

"It depletes confidence that BP have complete control of what is going on and their ability to collect the oil or cap it eventually."