Why time is against Iran's Mahmoud Ahmadinejad

- Published

Mr Ahmadinejad has been in China visiting the Shanghai World Expo

Twelve months on from President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's bitterly disputed re-election, Iran is both back to normal and changed forever.

The opposition protests that brought millions out on to the streets have petered out. Opposition supporters seem disillusioned, not just with their own government but with the opposition leadership as well.

The two main opposition leaders, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, have called off protests planned for the weekend, saying they do not want to cause the loss of innocent lives.

The government continues to insist that all the trouble was caused by a tiny handful of foreign-inspired rioters and troublemakers.

But they betray their sense of insecurity by their endless succession of warnings and triumphant declarations about how they have vanquished the enemy.

Witnesses say the streets of Tehran have been flooded for days with unprecedented numbers of police and members of the security forces. The odds are stacked against anyone who still wants to go out and protest.

After the government's initially hesitant response to the demonstrations last summer, the apparatus of repression has been honed and hardened.

Monitoring of the internet and phones has risen to new levels, making it ever harder to receive reliable information out of the country. Opposition supporters and journalists continue to be arrested.

Even Iranian exiles have become steadily less willing to speak out, as they continue to receive threats from the intelligence services and the Revolutionary Guards back in Iran.

Many Iranians have fallen into a sullen acquiescence, frustrated that their hopes for change have slipped away.

But in the longer term, trends may be against President Ahmadinejad and those around him.

Divisions at the centre

There was a revealing glimpse of the divisions at the heart of the establishment during a ceremony to commemorate the death of Ayatollah Khomeini on Friday, 4 June.

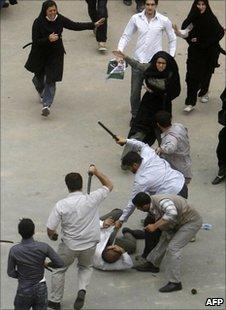

Opposition leaders fear a new crackdown like that of last year

During prayers at the Imam Khomeini shrine outside Tehran, Ayatollah Khomeini's grandson, Hassan Khomeini, was barracked and shouted down by a huge crowd brought in to express support for President Ahmadinejad and the supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei.

Hassan Khomeini is known as a supporter of the reformist movement. The incident shocked many Iranians who see Hassan Khomeini as the keeper of the flame for the revolutionary leader who still inspires respect.

And it is clear that many key establishment figures are giving only very reluctant support to President Ahmadinejad.

Former President Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani has kept a very low profile. Even the speaker of parliament, Ali Larijani, is no enthusiast.

As a result, a weakened president has had to compromise over a key plank of his domestic policy, subsidy reform, and has lacked the authority to negotiate freely over the nuclear programme.

Even more seriously, the economic trends are not good. Through a combination of mismanagement and international pressure, oil production is going down fairly rapidly, from 4.1 million barrels a day to 3.5 million barrels a day over the past two years.

Gas production is not coming through to replace it either. Amazingly this country of huge gas reserves is probably a net importer of gas.

At the same time, vast swathes of the economy have been virtually handed over to the Revolutionary Guards, part of their hugely increased power since the election.

They are not famed for their skills at economic management. According to one economist, following their recent takeover of the state telecom company 12,000 extra employees were taken on, many of them presumably loyal supporters, either being rewarded or being used for stepped-up monitoring of communications.

The government seems unable to reverse the big increase in spending made by President Ahmadinejad when oil prices were at record levels. Again, it lacks the authority to make the tough decisions that might have to be made.

There is much discussion if or when an economic "crunch" could come. The main symptom could be a crisis over the exchange rate and foreign currency reserves.

The political significance could be enormous if the government begins to run out of money to pay its loyal supporters in the security forces, not to mention the many millions of Iranians now employed in state-owned enterprises.

Class factor

During last summer's protests, the missing element was widespread labour unrest. Since then, there have been sporadic strikes, mostly over unpaid wages, but no sign of a wider, politically inspired, general strike that would be hugely damaging to the government and the system. Any glimmer of that would be a big danger for the government.

But the labour issue also illustrates a weakness of the Green movement. Despite the unpopularity of President Ahmadinejad, they have been unable to broaden their core support into the working classes, and also into the diverse regions of Iran, where the different ethnic groups have also been antagonised by Mr Ahmadinejad.

A majority may oppose Mr Ahmadinejad, and almost certainly voted against him in last summer's election. But they are not yet active supporters of Mir Hossein Mousavi or Mehdi Karroubi.

So it is still possible the government could get away with its continued mismanagement of the economy by continuing to repress dissent, even as this resource-rich country slips into poverty.

In another way, though, time is against Mr Ahmadinejad. The population is overwhelmingly young, it is well educated and it is outward looking.

Despite the misleading talk about Mr Ahmadinejad's rural base, the vast majority now live in the cities. And more and more Iranians would think of themselves as middle class, with aspirations to lead a freer, more secular lifestyle.

Iranians will proudly remind you of many aspects of their history. One of those is the country's history of popular rebellion that has shaped Iranian society and government for more than 100 years.

It is hard to see an Iranian government surviving indefinitely while it is so divided within, and so bitterly opposed by large numbers of ordinary Iranians.

Jon Leyne was expelled from Iran in June 2009 in the aftermath of the elections.