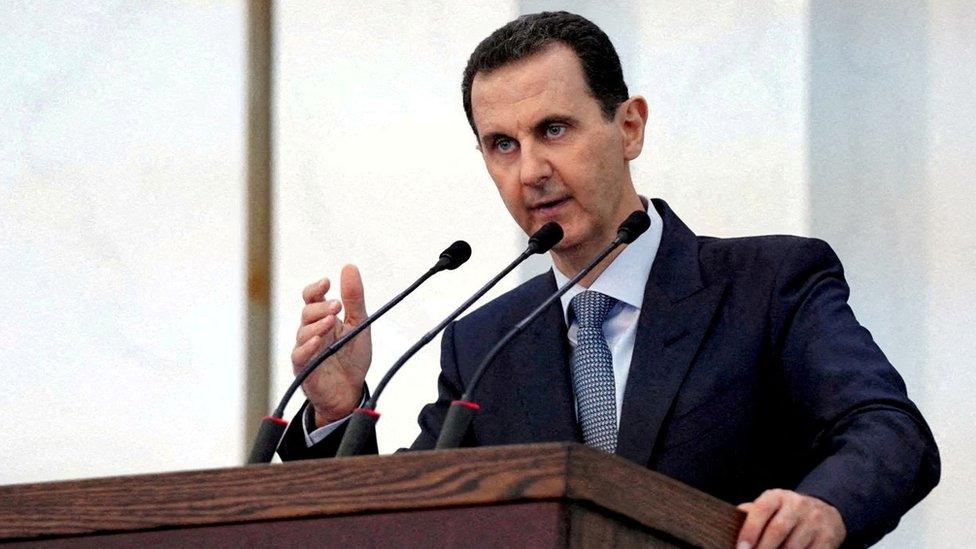

Bashar al-Assad: Sudden downfall ends decades of family's iron rule

- Published

Bashar al-Assad has stepped down as Syria's president and fled to Russia, bringing a sudden and stunning end to his 24-year rule.

Only two weeks ago, Assad had seemed to be secure after 13 years of civil war that erupted when he ordered a brutal crackdown on pro-democracy protests sparked by the so-called Arab Spring.

Russia, Iran and Iranian-backed militias had helped the military push the rebels trying to overthrow him into a small enclave in the north-west, and he had rejected calls to engage in negotiations on a political solution to end a conflict that has left more than half a million people dead.

But the fragility of Assad's government was exposed by the launch of a lightning offensive led by the Islamist militant group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham.

With Assad's foreign allies preoccupied with other wars, and unable or unwilling to help, his military collapsed within only 12 days as the rebels swept down the highway from Aleppo and captured Damascus with little resistance.

An unplanned president

Born on 11 September 1965, Bashar al-Assad was not always destined for the highest office.

As the second son of President Hafez al-Assad, he was largely left to follow his own interests.

He graduated from the College of Medicine of the University of Damascus in 1988 and then specialised in ophthalmology. In 1992, he went to London to pursue further studies.

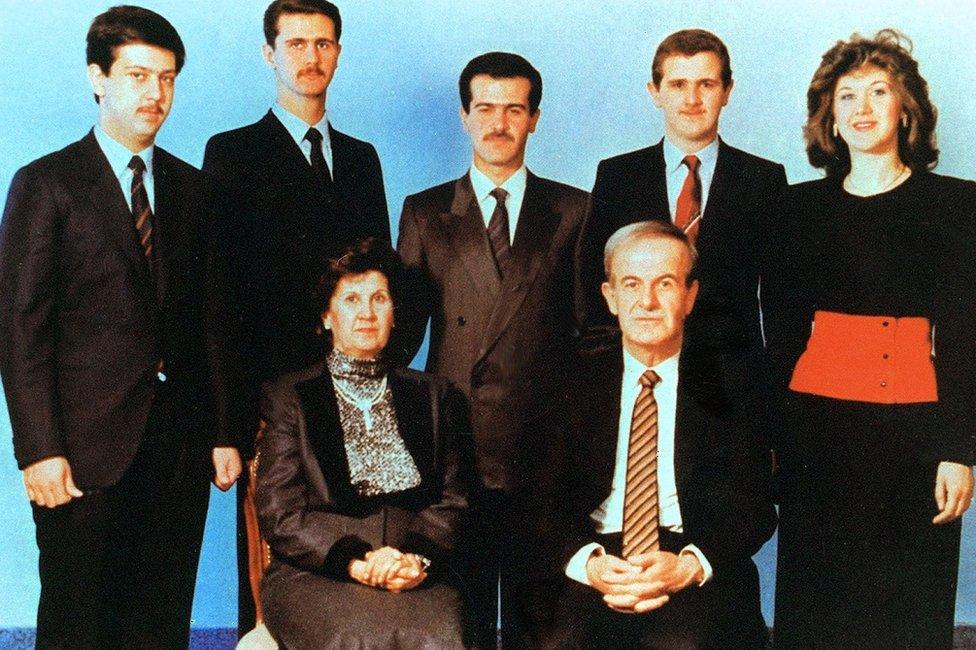

The Assad family has ruled Syria for more than four decades

After the death of his older brother Basil in a high-speed car crash in 1994, Mr Assad was hastily recalled from the UK and thrust into the spotlight.

He soon entered the Syrian military academy at Homs, and rose through the ranks to become an army colonel in 1999.

In the last years of his father's life, Assad emerged as an advocate of modernisation and the internet. He was also put in charge of a domestic anti-corruption drive.

Flirtation with reform

When his father died in June 2000 after more than a quarter of a century in power, Bashar al-Assad's path to the presidency was assured by loyalists in the security forces, military, ruling Baath Party and his minority Alawite sect.

He was appointed commander of the armed forces and secretary general of the Baath Party, before a referendum confirmed him as president.

Assad promised wide-ranging reforms, including modernising the economy, fighting corruption and launching "our own democratic experience".

Bashar al-Assad and his British-born wife Asma were welcomed to the UK in 2002

It was not long before the authorities released hundreds of political prisoners and allowed the first independent newspapers for more than three decades to begin publishing. Intellectuals pressing for reforms were even permitted to hold public political meetings.

But the "Damascus Spring", as it became known, was short-lived.

By early 2001, the intellectuals' meetings began to be closed down, several leading opposition figures were arrested, and limits on the freedom of the press were put back in place.

For the rest of the decade, emergency rule remained in effect and what economic liberalisation there was appeared to benefit the elite and its allies.

In May 2007, Assad won another referendum with 97% of the vote - criticised as a sham by opposition groups - extending his term for another seven years.

Hardline diplomacy

In foreign policy, Bashar al-Assad continued his father's hardline policy towards Syria's historic foe Israel, which has occupied most of the Syrian Golan Heights since the 1967 Middle East war.

He insisted there will be no peace with Israel until occupied land was returned "in full" and supported Palestinian armed groups opposed to the Jewish state.

His vocal opposition to the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, and the Syrian authorities' tacit support of Iraqi insurgent groups, angered Washington, but it was popular in Syria and the wider region.

Syria withdrew its troops from Lebanon after being blamed for the assassination of Rafik Hariri

Syria's already tense ties with the US soured in the wake of a February 2005 bomb attack in Beirut that killed Lebanon's former Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri.

The finger of suspicion was immediately pointed at Assad, the Syrian security services, which dominated Lebanon, and the allied militant Lebanese Shia Islamist movement Hezbollah.

Despite Assad's denials of involvement, international outrage at the killing forced Syrian troops to withdraw from Lebanon that April, ending a 29-year military presence.

'External conspiracy'

When anti-government protests erupted in the southern Syrian city of Deraa in mid-March 2011, Assad appeared unsure how to respond.

At first, he insisted that calls for reform and economic grievances had been overshadowed by saboteurs who were part of an external conspiracy to undermine Syria's stability and unity.

Assad initially blamed a small number of troublemakers and saboteurs for the unrest in 2011

The following month, Assad lifted the hated Emergency Law that had been in place since 1963. But the crackdown against protesters was also stepped up, with soldiers and tanks sent into restive towns and cities to combat "armed criminal gangs".

Despite the security forces' efforts and pledges of reforms by the president, the uprising continued unabated in almost every part of the country. Opposition supporters began to take up arms, first to defend themselves and then to oust loyalist forces from their areas.

In January 2012, Assad vowed to crush what he called "terrorism" with an "iron fist".

Assad pressed ahead with holding a referendum on a new constitution which dropped an article giving the Baath Party unique status as the "leader of the state and society" and allowed new parties to be formed. But the charter was rejected by the opposition.

Homs, like many Syrian cities and towns, was devastated by the fighting

Over the next few months, pressure built on the president as rebels seized control of large parts of the north and east of the country, and the opposition National Coalition was recognised as "the legitimate representative" of the Syrian people by more than 100 countries.

By the end of the year, as the death toll passed 60,000, Assad had ruled out any peace talks with the rebels, whom he denounced as "enemies of God and puppets of the West".

Chemical weapons

In early 2013, pro-government forces launched offensives to recover territory in southern and western Syria. They also received a major boost when the Lebanese Shia militant group Hezbollah began sending members of its military wing to fight the rebels.

UN chemical weapons experts did not ascribe blame for the 2013 Sarin attack on the Ghouta

That August, Assad was forced on the defensive after his supporters were blamed for a chemical weapons attack on the outskirts of Damascus. Hundreds of people died after rockets containing the nerve agent Sarin were fired at rebel-held towns in the Ghouta region.

The US, UK and France concluded that the attack could only have been carried out by government forces, but the president blamed rebel fighters.

Although the Western powers did not carry out their threats to launch punitive air strikes, they did compel Assad to allow the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) to destroy Syria's declared chemical arsenal.

Assad's re-elections in 2014 and 2021 were dismissed by his opponents as farces

The disarmament process ended in June 2014, the same month that Mr Assad ran for a third term in office, winning 88.7% of votes cast in areas under his control. Other candidates were allowed on the ballot for the first time in decades, but many dismissed the election as a farce.

That summer also saw international attention largely shift away from the war between the Syrian government and opposition towards the threat posed by the jihadist group Islamic State (IS), which had overrun large swathes of Syria and Iraq and proclaimed the creation of a "caliphate".

Russian intervention

In the first half of 2015, the government suffered a string of defeats, losing control of the northern provincial city of Idlib to rebel factions and more territory in the east to IS.

Worried by his ally's precarious position, Russian President Vladimir Putin ordered the start of a major air campaign in support of Assad that September.

Russian air strikes were decisive in the battle for eastern Aleppo in 2016

The Russian military said its strikes would only target "terrorists", but activists said they repeatedly hit mainstream rebel groups and civilian areas.

The intervention swung the conflict heavily in Assad's favour.

Intense Russian air and missile strikes were decisive in the battles for the besieged rebel strongholds of eastern Aleppo in late 2016 and the Eastern Ghouta in early 2018.

UN human rights investigators accused government and Russian forces of committing war crimes during the offensives, which reportedly left hundreds of civilians dead and led to the forced displacement of tens of thousands.

Russia sent thousands of military personnel to Syria after 2015 to support the Assad government

The government was also accused by a joint UN-OPCW mission of being behind a Sarin attack on the rebel-held northern town of Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017, which opposition health officials say killed more than 80 people, and accused by Western powers of an attack allegedly involving the toxic chemical chlorine in the Eastern Ghouta town of Douma in April 2018 that rescue workers said left 40 dead.

The latter prompted the US, UK and France to conduct air strikes that they said targeted facilities associated with the "Syrian regime's chemical weapons programme".

Assad and the Russian military denied committing war crimes, and said the incidents in Khan Sheikhoun and Douma were "staged" by the opposition and their Western backers.

Battle for Idlib

After recapturing the Eastern Ghouta, pro-government forces set their sights on the last three opposition bastions.

They retook an enclave north of Homs in May 2018 and regained full control of Deraa province two months later. They then declared their intention to "liberate" Idlib province.

The UN warned there would be a "bloodbath" if the government launched an all-out assault on an area home to about three million civilians, half of them displaced from other parts of Syria.

Almost one million people were displaced by the fighting in Idlib in 2019 and 2020

Assad was not deterred, but the offensive was halted that September by an agreement between Russia and Turkey, which called for a "demilitarised buffer zone" along the front line and the withdrawal from it of the Islamist and jihadist fighters that dominated Idlib. However, the deal was never fully implemented, and fighting on the ground and air strikes continued.

In late 2019, Mr Assad's forces resumed their offensive. Hundreds of people were killed and almost a million fled their homes before Turkey and Russia agreed another ceasefire in March 2020.

Over the next four years, the front lines of the civil war were largely frozen and there was an extended lull in violence in the north-west, although sporadic clashes, air strikes and shelling continued.

Economic problems

In 2021, Assad was re-elected for a fourth term after officials said he had won 95% of the vote. But the opposition again dismissed the poll as a farce and Western powers said it was neither free nor fair.

The president was then forced to turn his attention to dealing with an economic crisis that caused the value of the Syrian pound to plummet on the black market and the prices of basic goods to skyrocket.

The hardship triggered angry protests in territory under the government's control for the first time since the start of the uprising.

In 2023, crowds in the southern province of Suweida openly called for the overthrow of Assad, echoing the chants of the pro-democracy uprising 12 years earlier, while there was also criticism from Assad's fellow Alawites.

Syria's economic crisis prompted crowds in government-controlled Suweida to openly called for Assad's overthrow in 2023

The government blamed Western sanctions and the banking collapse in Lebanon, but the state was also plagued by rampant corruption.

Members of Assad's family and others in the ruling elite amassed great wealth and some were even accused of involvement in the multi-billion dollar trade in the amphetamine Captagon - a charge the government denied.

Meanwhile, efforts to rehabilitate Assad and his government began among the mainly Sunni Arab states which had once backed the opposition but now believed the president was secure.

The rapprochement accelerated following the devastating earthquake that hit Turkey and north-western Syria, when once-hostile powers sent humanitarian aid to government-controlled areas.

That May, Assad was welcomed to an Arab League summit in Saudi Arabia, where he spoke of "a historic opportunity to rearrange our affairs with the least amount of foreign interference".

Downfall

Assad continued to rebuff calls to engage in a UN-led political process into 2024, when the Syrian civil war was reignited by the conflicts in Gaza and Lebanon.

Hayat Tahrir al-Sham - which dominated the rebels' last stronghold in the north-west - and allied rebel factions announced on 27 November that they had launched an offensive.

They said its aim was to "deter aggression", accusing the government and allied Iran-backed militias of escalating attacks on civilians.

Statues of Hafez al-Assad were toppled as his son's government collapsed in the face of a lightning rebel offensive

But it came at a time when Assad's key allies were distracted by their own conflicts. Hezbollah had been devastated by Israel's offensive in Lebanon, Israeli strikes had eliminated Iranian military commanders and facilities in Syria, and Russia was focused on the war in Ukraine.

Without them, Assad's forces were left exposed.

The president vowed to "crush" the rebels after they quickly captured Aleppo. However, his military was unable to stop them taking Hama and Homs as they swept down the highway to Damascus.

On Sunday, Russia said Assad had stepped down and left Syria, hours after the rebels entered the capital and declared that "the tyrant" had fled.

Later, Russian media cited a Kremlin source as saying that he had flown to Moscow and been offered asylum on "humanitarian grounds".

There was no word from Assad himself, though, as Syrians celebrated on the streets and expressed disbelief at the dramatic close to five decades of dynastic rule.