Harper Lee's To Kill a Mockingbird turns 50

- Published

It's one of the best loved books in American literature, but To Kill a Mockingbird was also a one-hit wonder.

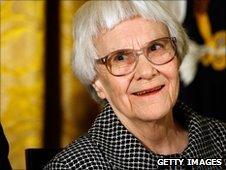

Author Harper Lee received a Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2005

Harper Lee's classic was published 50 years ago this summer and it remains the only novel she ever wrote.

Lee, 84, has never explained why she stopped writing.

She doesn't give interviews - "Hell, no" was her response to a request several decades ago - and that silence has only added to the intrigue.

But her close friend Thomas Lane Butts, a retired minister in her hometown, Monroeville, Alabama, says she once told him the reason.

Sitting on a pew in the Methodist church which the Lee family still attends, he described to me how she suddenly brought the subject up one night over dinner in New York.

'Conflict of the human soul'

"She asked me, 'You ever wonder why I didn't write anything else?' And I said, 'Along with several million other people, yes, I had wondered about that.' And she said, 'Well, what do you think?'"

Harper Lee watched director Alan Pakula transform her book into a film

Speaking in his slow southern drawl, the Rev Butts, who just turned 80, suggested to her that she had already written a great book and therefore didn't need to compete with herself.

"And when I got through she said, 'You're all wrong.' I said, 'Alright, smart Alec. You tell me.' She said, 'I would not go through all the deprivation of privacy through which I went for this book again for any amount of money.'

"And she said, 'I did not need to write another book. I said what I wanted to say in that book.'"

Harper Lee called it a simple tale about the "conflict of the human soul" and Monroeville, Alabama, is where she drew her inspiration.

The story depicts the segregated South of her childhood, during the Depression. It was published at the height of the civil rights struggle.

The Rev Butts grew up 10 miles outside Monroeville. By the late 1950s, he says, he was a "fuzzy-cheeked young preacher" campaigning for an end to segregation.

He had met Martin Luther King Jr and signed a petition to boycott buses. The Ku Klux Klan had left a burning cross on his front lawn.

Hometown embrace

He says To Kill a Mockingbird was not well received in Monroeville when it was published.

"The people who were hard racist did not like it because of the implication of the book," the Rev Butts told me.

"The book revealed racism and that always frightens a racist - when you pull the cover off them.

"Those of us who stood up for civil rights were much encouraged by the book because in a very skilful and subtle way it addressed itself for justice."

But these days, the Rev Butts says, there is enormous civic pride in Monroeville.

The old courthouse, which Hollywood re-created for the film, now houses a museum to Harper Lee and the town's other literary icon, Truman Capote.

Capote was a childhood friend of hers and is thought to be the inspiration for the Dill character in To Kill a Mockingbird.

The town's residents often try to protect Lee, allowing her to live a normal life instead of being hounded by fans or bothered with prying questions.

"Being famous I'm sure is a lot of fun for a year or two. But after a while it gets old," the Rev Butts says. "She is not a recluse but she does hide from publicity."