Q&A: Global whaling deal negotiations

- Published

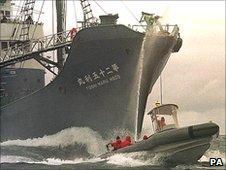

A deal that could regulate whaling for the next 10 years is being debated at the International Whaling Commission's (IWC) week-long meeting in Agadir, Morocco.

Environment correspondent Richard Black, who is at the talks, looks at the proposals drawn up by the IWC's chairman and considers the likelihood of the measures being adopted.

What is the "deal"?

On the table is a draft compromise "package" of measures that has been drawn up by the IWC chair and vice-chair following a two-year sequence of meetings with a small group of delegations. If adopted, it would reform whaling for a 10-year period.

The essential ingredients of the deal are that Japan would phase down (or phase out) its whaling operations in the Southern Ocean. The draft calls for its annual minke whale quota to fall from 935 to 400 now, and then to 200 in 2015.

In exchange, it would be assigned a quota for whales in its coastal waters.

Iceland and Norway would also receive quotas set by the IWC that could be smaller than the quotas they currently award themselves.

The three countries would agree not to go hunting unilaterally; Japan would agree not to use the "scientific whaling" clause. No other countries would be permitted to begin hunting.

Quotas would initially be set by political agreement, but the IWC's scientific committee would be able to mandate cuts if there was evidence that whale stocks were being threatened.

Measures such as observers on whaling boats and a DNA register for meat would be introduced, in order to prevent illegal hunting.

Most countries also want to see a clause adopted that would limit whalemeat to domestic consumption only.

Subsistence hunting by indigenous groups (such as the Greenland Inuit) would largely be unaffected.

Why do some conservation groups hate it?

Because in their eyes it legitimises commercial whaling, which has been under a global moratorium since 1986.

It would also - as it stands - permit some hunting of species listed as endangered, such as the fin whale.

Some are worried that if it was passed, some other countries would try to begin hunts - South Korea has already indicated such a wish.

Why do other conservation groups like it?

Under the global moratorium, as many as 2,000 whales are killed each year by Japan, Iceland and Norway. These countries set quotas unilaterally and there is little international oversight.

Could the deal end years of acrimony between pro- and anti-whaling groups?

They say that although the moratorium has been a real achievement, it is clearly not working for these three countries.

They see the deal as potentially reducing the number of whales being killed each year - perhaps down to half of current levels - and putting existing whaling under international oversight.

However, none of them back the draft proposals in their current form, and want certain elements tightened up.

They would also like to see the IWC get involved in other issues that threaten whales, such as climate change. At present, the commission is unable to turn its full attention to other matters, because the hunting issue is so divisive.

How would Japan benefit from the proposed deal?

It would see an end to the annual acrimony and international condemnation.

The deal would secure quotas for Japanese coastal communities with a history of whaling.

There is also a view among some negotiators that Japan's government is becoming concerned about the cost of the Antarctic expeditions, and is looking for to find an exit strategy.

Will IWC member nations accept the proposals?

Very hard to call.

As it stands, the package falls short of what anti-whaling countries want in some areas. A revised version is likely to emerge at some point during the talks.

However, while they are looking for deeper cuts in Japan's Antarctic hunt, Japan itself says the existing figures are too low.

The backers - principally the US - want to secure a consensus agreement. That looks to be a vain hope; there is unlikely to be any formulation that can satisfy both Australia at one end of the spectrum of opinions, and Iceland at the other.

In the absence of a consensus, IWC members will vote on the proposed measures. A three-quarters majority would be needed to bring about the change.

- Published21 June 2010

- Published20 June 2010

- Published27 May 2010