Who cares about the Chinese yuan?

- Published

Will a more flexible yuan be in China's own long term interest?

China looks set to allow its currency to rise in value against the US dollar for the first time in two years.

It is a move that has been demanded for months by angry politicians in Washington.

They say that China's currency is undervalued and gives the country an unfair competitive advantage.

But the new "flexible" yuan could have much more far-reaching implications than this.

THE WINNERS:

US toymakers will find it easier to compete with Chinese imports

Global trade, and all those involved in it, may be able to breathe a collective sigh of relief. Although at this stage the Chinese announcement is woefully short on detail, it should go some way to silencing the growing drumbeat of trade war emanating from Washington DC and elsewhere.

Foreign manufacturers that compete with Chinese imports will be smiling - think of toymakers and clothes makers in the US. Also, other big exporting countries such as Japan, Korea, Taiwan and Germany will gain a competitive advantage over their Chinese rivals.

Foreign companies (particularly in the US) that export to China will become more competitive. These include carmakers, technology companies and engineering firms. The price of their goods in yuan will be cheaper, and the money they earn in China will be worth more in their home currency.

Chinese companies that have borrowed in dollars will find the cost of their debt falls. Big winners here will include the Chinese airlines.

Long-suffering Chinese consumers will benefit from cheaper imports. However, households in China will continue to suffer from artificially low deposit rates, which mean they earn very little return on their savings.

Speculators who anticipated the central bank's announcement borrowed in dollars and bought Chinese assets, including property and Chinese shares. Others speculated on currency forward contracts, which have jumped in value on Monday.

Central bankers in China have been lobbying the government to let it do more to combat rising inflation in China. They have been fighting over policy with export industry lobbyists. A stronger yuan will help by lowering export prices and cooling the Chinese economy. The move will also make it easier for other Asian central banks, who face rising inflation, to raise interest rates and let their own currencies appreciate.

THE LOSERS:

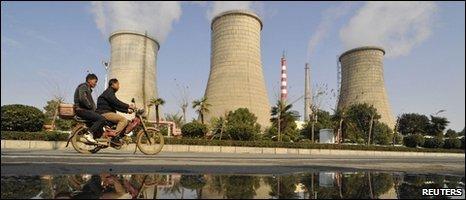

A rising yuan could be bad news for global carbon emissions

Chinese exporters, including foreign companies that own factories in China, will become less competitive. These companies pay wages in yuan, but set export prices in dollars and euros. Some, such as Toyota and Honda, are already facing strikes by Chinese workers to raise their wages. Many exporters operate on very thin profit margins that could be wiped out by the yuan's rise.

Foreign consumers, especially in the US, will have to pay more for goods made in China.

A rising yuan could be bad news for the environment, as it will make it cheaper for China to import raw materials and energy resources. The country's heavy industries are already widely criticised for poor standards of air, water and soil pollution. China is also the world's biggest growing producer of carbon emissions.

The People's Bank of China will be a big loser, even though its bankers may be happy about the policy change. Because of the central bank's currency policy, it has borrowed trillions in yuan and invested it in US treasuries and other dollar assets. The value of those treasuries in yuan is now set to fall, causing the central bank tens of billions of dollars in paper losses.

UNCERTAIN:

China has a voracious appetite for commodities

Europe may not benefit from the new yuan policy as much as the US. The yuan is currently pegged to the dollar, so any "flexibility" will directly impact US competitiveness. Indeed, the eurozone and the UK may actually lose out if Beijing decides to start linking its currency more closely to the euro and the pound. If the Chinese central bank starts buying these currencies, it will push their value up, making Europe less competitive.

Chinese heavy industry will need to pay less for the commodities - particularly metals and energy - that they import. For companies that focus on exports, this will go some way to alleviating their loss of competitiveness. But for companies that focus on the domestic Chinese market, cheaper raw materials are an unmitigated plus.

Commodities exporters such as Russia, Australia and Brazil may find demand from China - their most important customer - cools, as the demand from Chinese exporters cools. Alternatively, demand may pick up, as China can buy more raw materials at a cheaper price for their domestic markets. Commodity markets took the news very well so many clearly predict the latter.

The new yuan policy may prove a pyrrhic victory for the US politicians who have lobbied so much for it. There will after all be no immediate rise in the yuan. But the congressmen currently preparing a retaliatory trade sanctions bill against China may find the wind taken out of their sails. The US Treasury Secretary, Timothy Geithner, had started talking tough ahead of the G20 summit in Toronto later this month, but may now revert to quiet diplomacy.