10,000 NHS patients 'to have genes mapped'

- Published

An NHS hospital has begun decoding all the genes of individual patients, 10 years after the first human genome sequence was published.

London's Royal Brompton Hospital said the project would give doctors a better understanding of the inherited factors that help trigger heart disease.

The research involves sequencing all 22,000 genes found in the human genome in 10,000 patients.

It heralds more personalised treatments for diseases.

Genes are chunks of DNA that contain instructions for making chemicals in the body. As well as controlling things like eye and hair colour, faults in genes may make people susceptible to disease.

The sections of DNA that make up all a person's genes are known as the exome. Although genes represent only about 1% of the entire genome, they contain most of the key information for diagnosing inherited disease and for finding targets for new treatments.

In all 10,000 patients will have their genes sequenced at the Royal Brompton Hospital, which specialises in the treatment of heart and lung conditions, over the next 10 years.

They will also have a detailed MRI scan of the heart to show how it is functioning. The study has been made possible because of dramatic progress in the speed of DNA sequencing.

The research project is funded by the National Institute for Health Research,, external which awarded £6m over four years.

It is headed by Professor Dudley Pennell, director of the cardiovascular magnetic resonance unit at the Royal Brompton and professor of cardiology at Imperial College London.

He said: "Ultimately our aim is for someone to come in and have a full scan and genetic analysis, leading to a personalised therapy which will treat their particular disease."

Professor Dame Sally Davies, director general of research and development for the Department of Health and NHS, said the project was "terribly exciting".

She said: "Ten years after the first full sequencing of the human genome, it's now coming to patients and this will herald more individualised treatments."

Although the research is targeting the genetic causes of cardiomyopathy, or heart muscle disease, the sequencing may reveal inherited risk factors for other conditions.

Patients have to undergo extensive genetic counselling before their results are revealed.

Landmark

Ten years ago this week, Bill Clinton and Tony Blair held simultaneous press conferences in the White House and Downing Street to announce the first draft human genome had been completed.

Scientists at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, external near Cambridge did more of the sequencing than any of the 20 labs involved around the world.

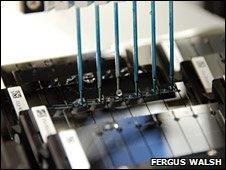

DNA samples can be analysed en masse

That project was billed as one of the greatest medical breakthroughs in history. It took 13 years to completely sequence the first human genome. The Sanger Institute can now sequence an entire genome in 13 hours.

Scientists say the more patients that are screened, the more we will understand which genes are responsible for triggering disease.

Professor Mike Stratton, director of the Sanger Institute, said it should increasingly lead to more personalised medicine.

"The new therapies that are in development will be applicable to some people and not to others and the choice of therapies for individuals will be determined by what is present in their genome.

"That is going to be good for patients because they will get the right drugs for them, and good for the health service as they won't be giving the wrong drugs to the wrong patients."

The Sanger Institute is part of the 1000 Genomes Project, an international public-private consortium to build the most detailed map of human genetic variation to date.

It has announced the completion of three pilot projects and that work has begun on building a public database containing information from the genomes of 2,500 people from 27 populations around the world.