Israel pressure to reform ultra-orthodox schools

- Published

Ultra orthodox, or Haredi, Jews make up 10% of the Israeli population and

For thousands of years the way that ultra-orthodox Jewish children are taught has changed little and is based almost entirely on study of the Torah - the Jewish Bible.

But now a group of leading secular Israelis wants to force the ultra-orthodox, or Haredi, education system to modernise and adopt standard subjects like maths, science and English.

The reason, they say, is that thousands of Haredi students are unable or unwilling to participate in wider Israeli society and are becoming an increasing economic burden.

Last week, in ultra-orthodox Jewish neighbourhoods of Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, more than 100,000 devoutly religious men took to the streets in protest.

On this occasion the men, clad in the traditional plain black clothing and distinctive headgear of Ashkenazi Jews, were campaigning for the right to educate their children separately from other Israelis - even from other Jews.

Education has become the focus of the many tensions between modern secular and ultra-orthodox Israelis.

A few days ago I was given rare access to the traditional and private world of ultra-orthodox education.

The Kol HaTorah Yeshiva, or religious seminary, in Jerusalem is regarded as one of the finest seats of learning for young ultra-orthodox boys.

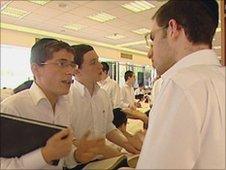

In one, huge classroom several hundred boys - huddled together in groups of two or three - argued noisily.

Dressed in black trousers, plain white shirts with black velvet "kippas" or skullcaps, these teenagers were debating passionately - not about politics, history or sociology but about the Talmud - Jewish Bible studies.

It's all they study, day in day out.

Students at a Haredi seminary dedicate their lives to Bible study

About 10% of Israelis are ultra-orthodox, or Haredi - a figure that is growing, partly because they have very large families. One of the teachers at the seminary is Rabbi Yechezekel Koren.

He has 13 children of his own, all following an ultra-orthodox way of life.

The rabbi acknowledges that most of the boys he teaches will never work or participate in "wider" Israeli society - dedicating themselves instead to a life of religious study.

"We try to keep the way we've been doing things for generations - for hundreds, even thousands of years," he says. "It's the same idea of studying the Talmud, an explanation of the Torah. We see the success, the great success and don't want to change a thing."

Mixed education

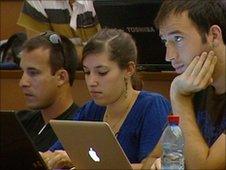

An hour's drive from the Jerusalem yeshiva, but separated by thousands of years of style and tradition, is the thoroughly modern IDC College in Hertzliya.

It is a mixed campus of young men and women dressed casually and learning together.

Zammi Kobalkin went through the Haredi education system, but found himself totally unable to integrate outside that community.

"I didn't start doing my A,B,Cs until I was 23," says Zammi, who has now joined mainstream education and is a law student at Herzliya, but at the cost of being disowned by his ultra-orthodox family in Jerusalem.

Most Israelis are still educated in a mixed, secular environment. They use lap-top computers and study a wide range of modern subjects.

But the increasing number of ultra-orthodox students, funded by the state, is a dynamic problem that has to be addressed, says Professor Amnon Rubenstein. He is a former minister of education in Israel and now lectures at IDC.

"If you don't teach them maths, English or computing they cannot be integrated into Israeli society," says the professor, who has co-sponsored a petition before the Israeli Supreme Court which would force ultra-orthodox schools to teach some core, secular subjects.

Most Israelis study a secular curriculum in mixed schools

"A growing number of Haredim, who don't know anything about the outside world is a real burden on the economy and wider society," he adds.

Some, less strict Haredi schools, have relented and now teach a few lessons from the wider curriculum. But, sitting studiously beneath pictures of famous rabbis and reading passages from the Torah, most of what they learn is still Bible studies.

The debate over education between secular Israelis and the ultra-orthodox is passionate.

There have been some changes but both communities are still a long way apart.

- Published18 June 2010