No prosecution for right-to-die doctor

- Published

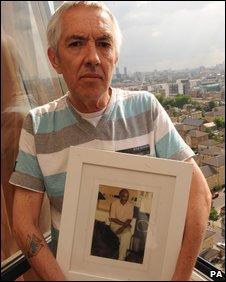

Dr Michael Irwin was arrested in 2009 after Mr Cutkelvin died

A former GP and right-to-die campaigner who took a man to a euthanasia group in Switzerland will not be prosecuted.

Dr Michael Irwin, 79, of Surrey, was arrested after cancer sufferer Raymond Cutkelvin, of London, died at Dignitas in Zurich.

But on Friday, Director of Public Prosecutions Keir Starmer said while there was enough evidence to prosecute, it would not be in the public interest.

Mr Cutkelvin's partner, who accompanied him, will also not face prosecution.

'Compassion'

Mr Cutkelvin was diagnosed with inoperable pancreatic cancer in 2006. He died the following year at Dignitas aged 58.

In a statement, Mr Starmer said Mr Cutkelvin had "reached a voluntary, clear, settled and informed wish to commit suicide".

Alan Rees, his partner of 28 years, helped pay for the assisted suicide and accompanied him to Switzerland, but was "wholly motivated by compassion", the director of public prosecutions (DPP) said.

"Mr Rees acted throughout as a supportive and loving partner," he said, and his actions amounted to "reluctant encouragement or assistance in the face of a determined wish by Mr Cutkelvin".

Mr Starmer said he therefore concluded that Mr Rees should not face prosecution.

The DPP said the circumstances of Dr Irwin's involvement were more complex, but he also should not be charged.

Dr Irwin claims to have taken three terminally-ill people to Dignitas and personally paid £1,500 towards Mr Cutkelvin's procedure there. Both of these factors could be seen to support prosecution, the DPP said.

Mr Starmer also said that during his career Dr Irwin was "motivated by a strong belief that the law on assisted suicide is wrong" and it should be acceptable to help someone to die.

And he noted that Dr Irwin was struck off the medical register in 2005 and received a caution for possessing a fatal dose of barbiturates that he intended to supply to a doctor friend.

Despite these factors, however, the DPP said: "Dr Irwin did not act for personal gain; did not put pressure on Mr Cutkelvin; and did not take an active part in the suicide itself."

His advanced age and the fact that he was motivated "at least in part by personal sympathy" all supported the decision not to prosecute, Mr Starmer added.

'Open and transparent'

Reacting to the decision, Dr Irwin said he was relieved the matter was now resolved, but wanted to keep the issue of the "two-tier system in this country" in the spotlight.

Mr Rees was Mr Cutkelvin's partner for 28 years

"If you have got money and are terminally ill, you can go to Switzerland for assisted suicide," he said. "But if you have not got money, you are stuck here and possibilities and outcomes remain uncertain.

"The law should be changed to make it possible to be fair, for it to be out in the open and transparent."

Mr Rees also said he was pleased with the decision, but criticised the length of time taken by the Crown Prosecution Service to reach it.

"In my opinion, no-one should be arrested for helping end the suffering of a loved one on compassionate grounds," he said.

"The loss of my beloved partner is difficult to bear without having to cope with possible legal action."

'Dangerous decisions'

Dr Irwin stood down as chairman of the then Voluntary Euthanasia Society, now renamed Dignity in Dying, after receiving his police caution.

Following Friday's decision, Sarah Wootton, from Dignity in Dying, said "people should not be forced to take the law into their own hands to have what they consider to be a dignified death".

Guidelines on assisted suicide were published in February, stating that anyone acting with compassion to help end another life was unlikely to face criminal charges.

Ms Wootton said the case of Mr Cutkelvin showed these guidelines were being followed, but added: "Parliament cannot continue to bury its head in the sand and pretend that people are not taking drastic and sometimes dangerous decisions."

Assisting a suicide remains a criminal offence in England and Wales, punishable by up to 14 years in prison.

And Mr Starmer added that "nothing in this decision should be taken as an indication that particular acts will not be investigated in the future or that they would not form the basis for a charge on other facts".