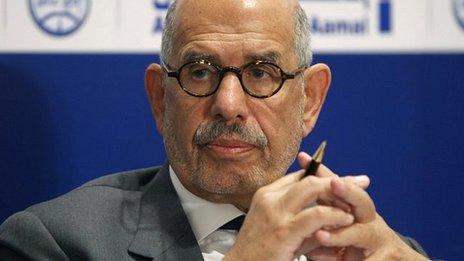

Profile: Mohamed ElBaradei

- Published

Mohamed ElBaradei, a Nobel peace laureate and former head of the UN's nuclear watchdog, emerged as a key political player in Egypt's post-Mubarak - and then the post-Morsi - era.

As the announcement was made that President Mohammed Morsi, Egypt's first democratically elected leader, was being ousted after barely a year in power, Mr ElBaradei was standing near the head of the armed forces.

As co-ordinator of the main alliance of liberal and left-wing parties and youth groups, the National Salvation Front, he was seen as a potential leader of the transitional government.

But his candidacy as prime minister failed when the hardline Salafist Nour party objected, and he was instead named interim vice president in July.

He resigned from that position on 14 August after Egyptian security forces led a bloody crackdown on supporters of Mr Morsi. Hundreds of people died when police and the army moved in to clear two protest camps in the capital Cairo.

"I cannot continue in shouldering the responsibility for decisions I do not agree with and I fear their consequences," Mr ElBaradei said in a statement. "I cannot shoulder the responsibility for a single drop of blood."

In 2012 he had been set to stand as a liberal, secular candidate in the presidential elections, but withdrew his bid in January of that year citing concerns about the undemocratic way the military was governing Egypt.

Mr ElBaradei had wanted a new constitution to be drawn up from scratch before any elections took place. In April 2012, he took to Twitter calling the transition to democracy "bungled" and criticising the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces' (Scaf) approach to writing a new constitution.

Although he stepped out of the presidential race, Mr ElBaradei had set his sights on gaining power in 2016 after forming a new political party in April 2012.

Diplomatic career

Born in Egypt in 1942, Mr ElBaradei studied law at the University of Cairo. He began his career in the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in 1964, and worked in Egypt's permanent mission to the UN both in New York and in Geneva.

Mohamed ElBaradei: "We were between a rock and a hard place"

He holds a doctorate in international law from New York University's law school.

In 1980 he became a senior fellow in charge of the International Law Programme at the UN's Institute for Training and Research.

Mr ElBaradei is married to Aida Elkachef, a teacher, with whom he has two children.

He joined the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) in 1984 and worked his way up to director general 13 years later.

Nuclear disagreements

Mr ElBaradei agreed with the administration of US President George W Bush on a number of key nuclear-related issues, but he was not afraid to speak his mind.

He particularly lambasted what he saw as double standards on the part of countries that have nuclear weapons but which seek to prevent others from procuring them.

"We must abandon the unworkable notion that it is morally reprehensible for some countries to pursue weapons of mass destruction, yet morally acceptable for others to rely on them for security - and indeed to continue to refine their capacities and postulate plans for their use," he once declared.

After taking over from Swedish diplomat Hans Blix in 1997, he employed diplomacy to deal with other nuclear rows in North Korea and Iran.

He insisted progress could be made even in the most difficult situations.

Mr ElBaradei earned political credibility in the Middle East when he questioned the claims about weapons of mass destruction that were being used to justify the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003.

His approach to Iran was perceived as not tough enough, by the Bush administration and its allies in the European Union.

Despite this, Mr ElBaradei won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2005 for his efforts to prevent nuclear proliferation.

Difficult homecoming

When he left the IAEA in November 2009, hundreds of his admirers defied warnings from Egyptian security forces three months later not to welcome him home at Cairo airport.

For some Egyptians, Mr ElBaradei's appeal lay in the fact that he is a civilian - Egypt had been ruled by the military since the monarchy was overthrown more than 50 years ago - and that he is untainted by corruption allegations.

But critics, back in 2012, suggested he was out of touch with the reality of Egypt and lacking in political experience.

Analysts said Mr ElBaradei was unlikely to win the presidential election even if he had run.

Although he played a prominent role in the Egyptian uprising that toppled Hosni Mubarak's regime and is a vocal critic of the Scaf's policies, his left-leaning politics have been eclipsed by the leading Islamist parties.

In April 2012, Mr ElBaradei launched a new political party which he said would be above ideology.

The Constitution Party came too late to field a candidate in the 2012 presidential election, but Mr ElBaradei said the aim was to take power in 2016, with Egyptians united behind democracy.

He openly criticised the transition of power to the new government and a new president in June 2012.

"You will have a president with imperial powers, he is going to be the legislator, he is going to be the executive, which is a total mess," he said.

"Theoretically he would have more power than Mr Mubarak... whoever is going to be elected is going to be a person with unchecked authority, and that is very frightening."

After Egyptians' protests over Mr Morsi's leadership escalated and eventually led to his demise, Mr ElBaradei said that he hoped a new plan to return the country to a democratically-elected government was "the beginning of a new launch for the 25 January revolution [of 2011]".