Honduras still split one year after president's removal

- Published

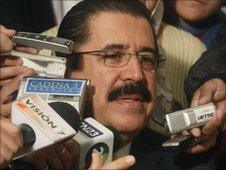

Manuel Zelaya currently lives in exile

A year ago this week Honduras plunged into deep uncertainty after the then President Manuel Zelaya was removed from office and expelled from the country.

It was the climax of a political crisis without precedent in this Central American nation.

Many in Honduras think that, 12 months on, the political divisions that precipitated the crisis have not subdued; some even argue that they have worsened.

"The country is a social, economic and political chaos," Patricia Licona, who was deputy foreign minister in the Zelaya administration, told the BBC from the Honduran capital, Tegucigalpa.

Mr Zelaya was removed from office amid a dispute over his plans to hold a vote to see if people were in favour of setting up an assembly, which would then look into altering some parts of the constitution.

His critics said the vote, which was ruled illegal by the Supreme Court, aimed to remove the current one-term limit on serving as president and pave the way for his possible re-election - a charge Mr Zelaya repeatedly denied.

Mr Zelaya's ousting sparked an international uproar and left Honduras politically isolated for several months.

However, a period of relative stability began with the election of Porfirio Lobo as president in the scheduled November elections.

More and more governments, including the US, recognised the Honduran government's legitimacy and re-established the ties cut during the height of the crisis.

But many countries, especially in South America, have yet to restore links.

Abuse allegations

The situation inside Honduras is complex. Amid allegations of serious human rights abuses, Mr Lobo's government is struggling to leave the crisis behind.

Since his inauguration in January, Mr Lobo has had to tackle the economic impact of both the world recession and the political upheaval on the country's feeble finances.

He is also still dealing with the political fallout from the crisis - and one of the thorniest challenges seems to be Mr Zelaya's own situation.

Porfirio Lobo has faced economic as well as political troubles

Immediately after he was removed from office, Mr Zelaya was flown to Costa Rica, spending the next few months making repeated attempts to return.

In September, he finally succeeded to sneak in and found refuge in the Brazilian embassy in Tegucigalpa.

But as Mr Lobo came to power, Mr Zelaya decided to leave the country and has since lived in exile in the Dominican Republic.

"We want him to be allowed to return, along with all the other Honduras who have been forced into exile," Ms Licona says.

In fact, Mr Lobo's government has shown willingness to allow Mr Zelaya's return, and, according to officials, the ball in now in his court.

"His intentions and his future depend only on him," said Mario Canahuati, the current foreign minister.

"We can't be paying attention to one person and forget about the eight million Hondurans," he adds.

Indeed, many in Honduras are concerned about what is happening on the ground.

International organisations have condemned the human rights situation in the country.

They have denounced persecution of those who opposed Mr Zelaya's removal, and say political activists have been murdered, raped, tortured and harassed.

In a letter to the Honduran attorney general last March, Human Rights Watch said that the fact that many of the victims of these crimes are activists suggest the abuses "may have been politically motivated".

One of the most worrying situations is that of journalists: since the beginning of this year, nine have been killed in Honduras.

The country, rights groups say, is fast becoming one of the most dangerous in the world to be a journalist.

The current government says it is investigating these specific allegations, but notes that Honduras is mired in a general crime wave stirred by the increasing presence of Mexican drug cartels on its soil.

'Never the same'

The concern in Honduras is how solid the new democratic order is.

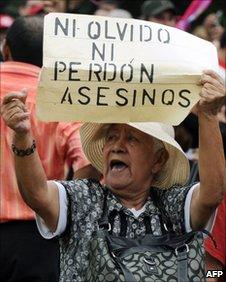

Zelaya supporters took to the streets to mark the anniversary of his removal

A few weeks ago, Mr Lobo himself denounced that he was being the victim of "destabilising efforts" from some sectors in the country unhappy with his handling of the country.

Rumours swirled around Honduras that the president had received messages saying "get your pyjamas" ready, in a clear reference to the clothes being worn by Mr Zelaya when a group of soldiers broke into the presidential palace and forced him into exile.

Many say that those who orchestrated Mr Zelaya's ousting and supported the interim administration of Roberto Micheletti do not trust President Lobo's efforts to reconcile the country.

"For example, when (Mr Lobo) sounds too indulgent with Zelaya's possible return, he irks part of the Honduran people", says Martha Lorena Alvarado, a conservative lawmaker who was deputy foreign minister under the Micheletti administration.

On the other hand, supporters of Manuel Zelaya have strongly criticised the government-appointed truth commission to investigate the political events of last year, and have this week set up a parallel inquiry.

The only thing for certain in Honduras now, Patricia Licona says, is that the country "will never be the same".

- Published8 June 2010