Cryosat-2 focuses on ice target

- Published

Cryosat tracks over the Ross Ice Shelf and Ross Sea on 11 April

The Cryosat-2 mission is delivering on its promise to make high-precision radar measurements of polar ice.

The first data from the European spacecraft has been presented at an Earth observation meeting in Norway.

The information clearly shows Cryosat has the required sensitivity to assess the state of Antarctic and Arctic ice, according to its lead scientist.

"All of the measurement concepts have been confirmed," UCL Professor Duncan Wingham told BBC News.

The Ross Ice Shelf is formed by landed glaciers that push out into the sea

The European Space Agency's Cryosat-2 satellite was launched in April on a quest to map the thickness and shape of the Earth's polar ice cover.

It carries a single instrument - a SAR/Interferometric Radar Altimeter (Siral) - which has a capability that far exceeds the previous space-borne radar technology used for this purpose.

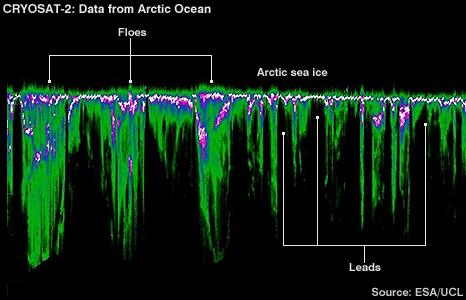

Siral has an along-track (straight ahead) resolution of about 250m, which will allow it to see the gaps of open water between the protruding sea-ice floes of the Arctic.

With centimetre-scale accuracy, the altimeter will measure the difference in height between the two surfaces so scientists can work out the overall volume of the marine cover.

A second antenna on Siral offset from the first by about a metre will enable the instrument to sense the shape of the ice below, returning more reliable information on slopes and ridges.

This interferometric observing mode will be used to assess the edges of Greenland and Antarctica where some rapid thinning has been detected in recent years.

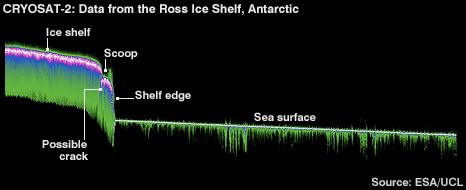

At Esa's Living Planet Symposium here in Bergen, Professor Wingham released radar data taken from a Cryosat pass over the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica.

It records the edge of the 400m-thick mass of ice, and the sudden drop to the seawater surface which is probably covered with a thin veneer of ice.

"It shows us coming off the shelf; it shows the scoop [or slumping] you often get at the edge as a result of melting underneath, and then our pass over the sea - although there must be a lot of ice in the water. It's very still; there are no waves on it," explained Professor Wingham.

"There's a feature in there that's so sharp, it's probably a fracture."

Another radar echo track, acquired this time in the Arctic, illustrates Cryosat's ability to see the gaps, or leads, in the ice - something it has to do to make an assessment of ice thickness. This only became possible last week after several weeks of calibration work on Siral.

Cryosat has to be able to distinguish the floes from the leads

"It's all starting to come into focus," said Professor Wingham.

Esa's mission operations team has had to work the spacecraft to get it into the correct orbit to do its science.

The Dnepr rocket put the satellite initially into an elliptical orbit that took the platform to too high an altitude to make optimal ice measurements.

This meant Cryosat had to fire its thrusters to tighten the ellipse, bringing the highest altitude down from 770km to under 760km; and the instrument was then re-tuned for the changed circumstances.

"We budgeted 15kg of fuel to acquire the initial orbit to allow for launch errors," said Dr Richard Francis, the Esa Cryosat project manager.

"What we actually used to achieve this [modified] orbit was 2.2kg. So, it was a lot less than we budgeted; we've got a lot of fuel left. We're now using about 2g a day in normal operations."

Esa expects to get at least five years of mission life out of the satellite.

The spacecraft is mid-way through a six-month commissioning phase. Once this is complete, calibrated and validated data will be delivered to the scientific community.