Long history of deep-cover 'illegals'

- Published

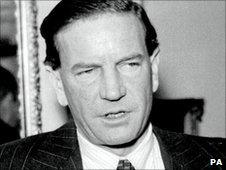

KGB recruits like Kim Philby passed countless British secrets to Moscow

The use of so-called "deep-cover illegals" and a patient approach to espionage are two hallmarks of Russian spying dating back nearly a century.

The golden age of the great Russian "illegals" - who were not just living without diplomatic cover and the protection that this provides, but were pretending to be nationalities other than Russian - lies back in the midst of time before even the dawn of the Cold War.

In the 1930s, the KGB's predecessor sent its men under deep cover into Europe, where they began recruiting young, idealistic men drawn to communism as the only force opposing fascism.

On a park bench in London a young Kim Philby, recently out of Cambridge, agreed to penetrate the British establishment.

He would later become the most famous of the former Cambridge undergraduates the KGB would call "the magnificent five".

The Russians had to wait half a decade before Philby actually made his way to a job in British intelligence, but after that he was priceless as the British state haemorrhaged its secrets to Moscow.

From the details released so far, none of the alleged agents involved in this latest operation look anything like as valuable. Few, if any secrets, appear to have been obtained.

Embarrassment

Many of the methods used by the suspected agents arrested in the US - the "brush contacts" in train stations - would have been familiar to those who recruited and ran Philby even if others - the use of wireless networks and steganography, the art of secret writing - would not.

The moment of greatest vulnerability for any spy has always been the meeting with their handler and the moment at which information is passed.

Technology offers new possibilities but also new methods of detection, as the FBI seems to have employed.

Running agents as illegals under deep cover requires a huge commitment of resources and time.

This case appears to show Russia's External Intelligence Service (SVR), the KGB's successor, is still willing to invest even for relatively low-level secrets, a position which some Western intelligence agencies will occasionally admit they envy slightly.

But getting caught is always embarrassing, especially when the reality that spying is often a mixture of the mundane and farcical, punctuated by moments of high drama, is exposed to public scrutiny.

Uncovered networks

The UK's Security Service, MI5, regularly complains that the number of Russian intelligence officers operating in London is at Cold War levels.

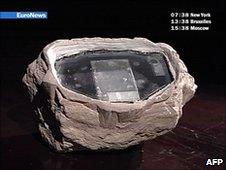

In 2006, Russia accused the UK of using a "spy rock" to send intelligence

Many of these officers will be working against Russians, and especially dissidents, in London.

The death of Alexander Litvinenko - who died from radiation poisoning in London in 2006 - remains a sore point between the two countries despite efforts to move on.

But it would be foolish and naive to think that the US and UK were not running their own operations in Russia to collect secrets.

In January 2006, the Russians accused the UK's Secret Intelligence Service, MI6, of using a "spy rock" to transmit information gathered by its agents in Moscow.

The Cold War may be over but for the Americans and Russians there are still plenty of important secrets to steal from each other - whether on the latest military technology, strategic intentions over Iran, energy supplies or manoeuvrings in Central Asia.

This means that both sides are almost certain to have many more agents and networks in place - and some may have burrowed far deeper and stolen much more than the group just allegedly discovered.