The ancient art of hidden writing

- Published

Trithemius wrote a long text about the art of hiding messages in text

The arrest of 10 alleged spies in the United States has thrust the ancient practice of steganography into the limelight.

Several of the suspects are accused of using the method to conceal data being transmitted from the US to Russia.

As you might expect for a technique that involves hiding information, steganography has always had a shady reputation.

That question mark over it dates from the text in which the word was coined, Steganographia, which was written in 1499 by Johannes Trithemius but not published until 1606.

The name of the book derives from the Greek for concealed writing and steganographic techniques involve hiding messages in otherwise innocent-looking media - be that text, images or video.

Steganographic techniques can be applied to lots of different media

Trithemius' text details a series of magical techniques that would enable anyone who could follow the maths to communicate over long distances by bending planetary spirits to their will.

Banned texts

Writing a spell book was decidedly dangerous during those God and Church fearing times; that Trithemius was the Abbot of Sponheim when he wrote the text was no defence.

The Catholic Church considered the three volumes of Steganographia to be so dangerous that it put them on its list of prohibited works. They stayed banned for almost 300 years.

Despite the prohibition, the texts were sought out by the growing number of Renaissance scholars who were part-scientist, part-theologian and wholly curious about the way the Universe worked.

One of the most famous of those men was the brilliant Englishman John Dee, Queen Elizabeth's astrologer and a man named as an "ornament of the age" by one of his biographers.

The text was particularly interesting for Dee because he was actively engaged in spirit magic and was an evangelist for the fledgling science of mathematics.

Dee was instrumental in having many of the foundational texts of mathematics, such as Euclid's Elements of Geometry, translated and distributed in Britain for the first time.

Modern-day analysis of the Steganographia shows that the tricky mathematics and magic were a ruse to keep this useful technique out of the hands of those that would abuse it.

The supposed magical rituals and communications with demons detailed in the third volume were actually ciphers, methods for turning text you want to hide into something less obvious.

That it took hundreds of years for this to be realised is perhaps a testament to how good steganography can be at concealing information.

Making sense

This also reveals the key to understanding it. While scrambled, encrypted text is easy to spot and hard to make plain, by contrast text hidden by steganography is hard to spot but relatively easy to make plain once you know it is there.

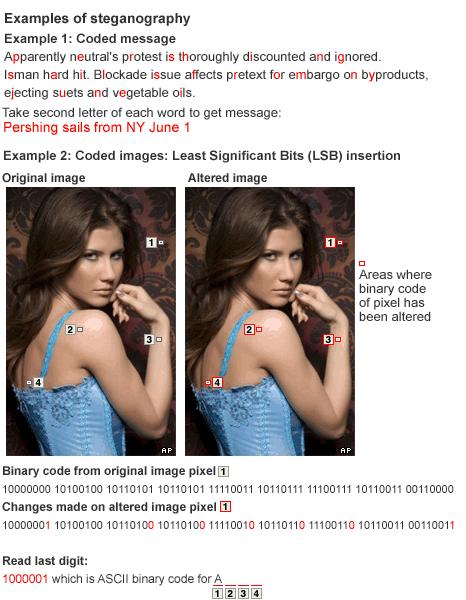

Modern-day steganographic techniques involve manipulating pixels

It is fair to say that those who are in the trade of hiding information have preferred to encrypt it rather than hide it with steganography. There are examples of it being used during World War II but encryption was far more popular.

The modern day and the rise of computers has re-ignited interest in it particularly as a way to hide text in all kinds of places such as images.

This technique involves making tiny changes to the values used to define the colour of a pixel. In a 24-bit image each pixel has its colour defined by three numbers - one for each channel - red, green and blue.

A tiny change to each pixel will alter its colour but not so much that humans could spot it. However with the right software, or a reference image, the changes would stand out.

The changes can be built up to number Ascii codes that define letters, and slowly build up a message.

Many claims have been made for different groups using this technique, called Least Significant Bit insertion, to pass secret messages back and forth. In 2001 there were claims that Al Qaeda was hiding messages in pornographic images.

However, searches of millions of images from all over the web have failed to turn up any evidence of hidden messages to Al Qaeda operatives working under deep cover in the West.

- Published29 June 2010