Turkey's Kurdish war reignites

- Published

Exactly a year ago Turkish Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan announced that he was working on a new plan to end the war with insurgents from the Kurdish Workers Party, or PKK, which has cost more than 40,000 lives.

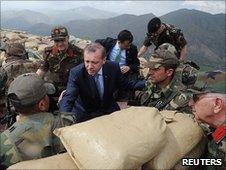

After talking of peace, Recep Tayyip Erdogan is now more hawkish

Today that plan has stalled, and new attacks by the PKK this year have reignited the conflict, killing more than 50 soldiers and prompting retaliatory raids by Turkish troops and aircraft into northern Iraq.

"Our nation wants unity," Mr Erdogan declared after meeting the main Kurdish party, the DTP, last August, to discuss his plans to end the conflict in the Kurdish south-east.

"It wants no more crying mothers, no more blood and killing".

It was the first time a Turkish government had promised to seek a solution through democratic, peaceful means.

There was talk of an end to restrictions on using the Kurdish language, new human rights bodies in the region, a new era between the Turkish state and its largest minority.

But by November the government had still not presented its plans to parliament, as promised.

'Democratic Opening'

"It was never a very precise project," says Professor Maya Arakon, from Yeditepe University in Istanbul.

"It came out of nowhere after the prime minister had returned from Washington, where he had been told by President [Barack] Obama of the US plan to pull out of Iraq by 2011."

Mr Obama asked Turkey to prepare to maintain stability in the region after the US left, which added pressure on Turkey to resolve tensions in the region.

PKK attacks in south-eastern Turkey are often carried out by rebels based in northern Iraq who cross the border to stage raids.

Mr Erdogan invited the two nationalist opposition parties to join him in formulating what he was now calling his "Democratic Opening". But they refused, accusing him of "selling out to terrorists".

"This should have been above party politics," says Professor Arakon.

"But the opposition thought only of appealing to their own supporters, of saying no to whatever the government proposed."

The opposition was given a perfect opportunity to attack the plan when the PKK announced in October that it was sending back 30 people from Iraq, including eight fighters from its armed wing, as a test of the government's sincerity.

Its jailed leader, Abdullah Ocalan, had already threatened to launch a "roadmap" of his own.

Loss of nerve

The PKK was staking out a part for itself in the Democratic Opening, although the government's main objective had been to isolate the insurgents.

Under normal circumstances, the fighters would have been arrested once they crossed the border, but they were released.

Anti-PKK sentiment runs strong in much of Turkey

However, when they arrived in the main Kurdish city of Diyarbakir they were given a heroes' welcome by tens of thousands of supporters.

This prompted a furious response from nationalists and veterans' groups in the rest of Turkey, who accused the PKK of trampling on the memories of the soldiers killed in the war.

The government lost its nerve. For years Turks have been conditioned to view the PKK as barbaric "terrorists". The group is listed as a terrorist organisation by the EU and the US.

The PKK's demand to be the main negotiator for the Kurds was politically unthinkable for any government.

So when Mr Erdogan finally presented the plan to parliament in November, it contained little detail.

Over the following month, the Constitutional Court banned the DTP over its alleged links to the PKK, and hundreds of local Kurdish officials were arrested by the authorities.

Rebel 'hawks'

For many Kurds, it seemed like business as usual again. "The opening is finished", declared DTP member of parliament Emine Ayna.

The PKK had declared a ceasefire in April 2009. But this year it began attacks on military targets as the winter snow retreated from its mountain strongholds.

On 31 May, Abdullah Ocalan announced from his prison cell that the ceasefire was over, that he had give up hope of a dialogue with the government.

"The PKK is being led by hawks at the moment", says Kurdish intellectual Umit Firat.

"The movement is led by men whose only skills are fighting, so they feel threatened by the Democratic Opening. They don't want to lose support to the governing party, they want their presence to be felt."

In recent weeks Mr Erdogan's language has also become more hawkish, threatening to drown the insurgents in their own blood. But he still argues that his Democratic Opening is the only way forward.

Other sectors of Turkish society are also weighing in.

The country's most powerful business association, TUSIAD, made a rare intervention on the subject, criticising the government's handling but also calling for new thinking.

A coalition of hundreds of non-governmental organisations and civil society groups in the south-east also came together in an appeal for both the PKK and the Turkish armed forces to stop fighting.

But there is little else the government can do now, losing support and just a year away from an election.

However, some things have changed.

Kurdish language and culture classes are being taught for the first time in universities in the south-east. And Kurdish politicians are constantly challenging the restrictions on the use of Kurdish during campaigns.

"This government's greatest achievement is that they have left the era of denial in the past," says Umit Firat, "They have declared that there is a Kurdish people and a Kurdish language."

- Published1 July 2010

- Published20 June 2010

- Published17 June 2010

- Published16 June 2010