Tags reveal puffin food 'hotspot'

- Published

GPS devices fitted to puffins have offered a valuable insight into the daily feeding patterns of the seabirds.

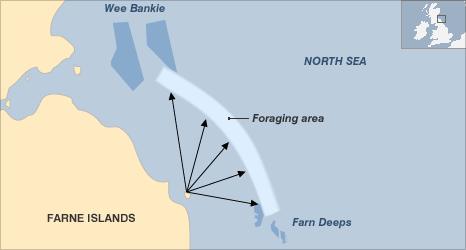

Data revealed that the birds headed for foraging "hotspots" about 20 miles away, much closer than previously thought.

Researchers fitted the logging devices to 12 adult birds at England's largest puffin colony on the Farne Islands.

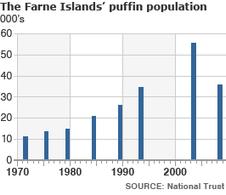

The team tagged the birds in an effort to find out why the islands' population crashed by 30% between 2003 and 2008.

The project's lead researcher, Richard Bevan from Newcastle University, said the technology had "come into its own" at the National Trust-owned site located off the Northumberland coastline.

"For the first time we can accurately pinpoint where puffins, kittiwakes and other seabirds are going to forage," he said.

"Knowing where these [species] go to feed is a vital factor in their survival."

Dr Bevan added that the data would help towards conserving and monitoring the feeding "hotspots", which in turn would provide a more secure future for the colony's birds.

The team used devices called "GPS loggers", which stored information rather than transmitting it in real-time. The loggers recorded the position of the tagged bird every minute for about three or four days.

The devices were attached to the birds with a glue that weakened after about four days, allowing the tags to be recovered and the data downloaded.

The data showed that the birds headed out about 20 miles from the islands, much less than the 60 miles that the researchers previously thought the puffins were flying in the search for food.

One of the favoured sites was an area of deep water known as the "Farnes Deep".

The collected information also showed that some of the tagged puffins took direct routes to gather sandeels for their chicks, while others favoured longer, circular journeys.

Another 16 adults were also fitted with time/depth recorders that showed how the birds dived for fish.

Rather than showing that the puffins were diving up to 25 metres beneath the waves to catch their prey, as was assumed, the recorders suggested that the birds were only going down to depths of four to five metres.

"This new research and our ongoing puffin counts are finally piecing together a complete picture of puffin behaviour," said David Steel, the National Trust's head warden on the Farne Islands.

"The puffins seem to be recovering slowly from the 2008 crash, with a 5% increase in numbers recorded both this year and last year."

Winter Odyssey

Earlier this year, a separate study, led by Professor Mike Harris from the Centre of Ecology and Hydrology, revealed that puffins from the North Sea's largest breeding colony on the Isle of May ventured much further afield during the winter than previously thought.

More than 75% of the 50 seabirds fitted with "geolocator" tags headed for the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean, rather than staying in the North Sea.

Until this study, very little was known about where puffins went during the winter as the birds spent the entire time at sea.

Professor Harris and his team said the findings challenged the previous view that puffin populations on the east and west of Britain remained separate from each other, during both the breeding season and during the winter.

Dr Bevan and the team of researchers from Newcastle University also fitted the tiny geolocator tags to the leg rings of eight puffins during 2009.

However, to date, only two have been recovered and they are waiting for the data to be extracted from the devices.