Budget cuts caution on UK nuclear waste plan

- Published

A German facility for low-level waste in an old mine is likely to open in 2013

The UK's deep store for nuclear waste should open for business around 2040 - but spending cuts could delay the plans, and community support is vital.

These are the key messages in a report from the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA), the agency charged with managing the nation's waste.

So far, only two Cumbrian communities have expressed interest in hosting a deep permanent repository.

The cost of developing such a facility is estimated at about £4bn.

The report - Geological Disposal: Steps Towards Implementation - is the NDA's roadmap for meeting the objectives and the timeline laid out by the previous government in its 2008 white paper.

A number of countries are some years ahead of the UK on this road, with Finland hoping to have its Onkalo repository accepting waste from 2020.

"All the experience internationally shows that if you just choose a technically good site and try to implement without buy-in from the local community, you're bound to fail," said Bruce McKirdy, managing director of NDA's Radioactive Waste Management Directorate.

"So you can't rush that first part; and this is how they've done it in Finland and Sweden."

Scandinavian models

The UK's nuclear waste problem is considerably bigger than either of the Scandinavian countries.

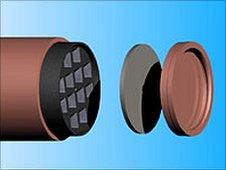

One option is the copper canister method to be used in Scandinavia

Its nuclear energy programme has been larger and it opened earlier, with initial prototype reactors generating much larger volumes of waste than later, standardised designs.

The total volume of waste from past and present operations amounts to about 500,000 cubic metres, although there is a huge variety in types of waste, the level of radioactivity and how long it will remain dangerously radioactive.

The coalition government has said it is committed to finding a long-term solution for the UK's nuclear waste problem.

But with public spending under review, and departments reportedly being asked to make contingency plans for cuts of up to 40%, NDA said continued funding was essential.

"Our funding requirements in the next few years are comparatively modest, around £20m per year," said Alun Ellis, NDA's repository project director.

"Something like a 40% cut would put us into a holding pattern, into hibernation; we'd maintain core technical capabilities, but wouldn't actually deliver the programme."

Going local

In geological terms, finding a suitable site in the UK is straightforward. The social side is more challenging.

In 2008, the government wrote to councils asking if any were interested in exploring the idea of hosting the UK's first deep repository.

Some waste is now stored at nuclear power stations such as Sizewell B

Three Cumbrian authorities have since come forward - Allerdale and Copeland Borough Councils, and Cumbria County Council.

They have formed a partnership called West Cumbrian Managing Radioactive Waste Safely (MRWS), and are currently going through a series of "stakeholder engagement" exercises.

The 2008 white paper promised incentives for any community that committed itself to hosting the site.

What those incentives might be is not yet clear - the communities themselves would have a lot of say in that - but in Sweden and Finland, jobs from the companies involved in building and managing the repository have been a key factor.

A survey by Mori last year found about half of residents in the Copeland and Allerdale area supported locating the repository in West Cumbria, while a quarter were opposed.

Currently, the Sellafield site nearby hosts more waste than any other UK installation.

"This is a group of people who are already quite familiar with the nuclear industry," said Elaine Woodburn, leader of Copeland Borough Council and its MRWS representative.

"But we would be managing something for the nation long-term, so it's only right that we'd receive long-term benefits from doing it, not just something like a road that would be gone after 100 years," she told BBC News.

The partnership is planning to reach a conclusion by the middle of next year on whether to proceed with talks aimed at tying up an agreement, or whether to pull out.

If no communities want the repository, said Alun Ellis, it will not be built.

"The government's answer to this question is that Plan B is to make Plan A work," he said.