Are graduates getting smarter?

- Published

It is an anxious time for thousands of students getting their degree results, but this year the stakes are higher than most.

A report last week by the Association of Graduate Recruiters found almost four out of five employers combing through job applications from graduates are insisting on a minimum 2:1 grade.

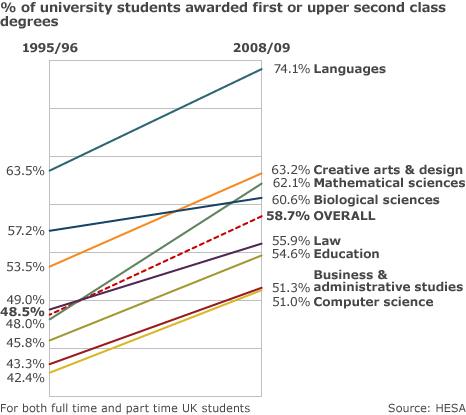

But if recruiters have raised the bar, some believe universities have done the opposite. Figures from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) show the number of students getting first class and 2:1 degrees to be rising.

You can see by clicking through this graph below how upper second degrees have risen while lower seconds and unclassified grades have fallen. Thirds have also gone up slightly. But the most remarkable trend has been the increase in first class degrees.

So are students getting brighter or is it getting easier to get a first class degree?

According to Nicola Dandridge, chief executive of umbrella organisation Universities UK, there are a number of factors to consider.

"Attainment, whether at A-level or through other routes, has been rising over the same period," she says.

"In addition, there is a widespread perception among many students that they need 'the essential 2:1' to be even considered by employers. That has undoubtedly driven students to work hard, which should be praised."

Subject successes

There is no suggestion that some degree subjects are "softer" and so skewing the results, with the average 10% increase in first class and 2:1 awards being borne out across most areas.

Mathematical sciences saw the sharpest rise in students getting an upper second class degree or above going from 48% in 1995 to 62% last year.

Students taking language degrees (including English) tend to do very well, with 74% obtaining a 2:1 or higher against 51% in computer science. Both have seen significant rises in the top grades.

Other possible explanations for the improving grades relate to changing assessment practices, involving more coursework and continuous assessment rather than examinations alone.

However, last year, the Parliamentary universities committee reported, external some academics' concerns about "an obvious decline in standards".

The suggestions were denied by the Russell Group of 20 leading UK universities, which pointed to a correlation between entrants being better qualified and the subsequent improvement in degree results.

However, Education Secretary Michael Gove recently cited universities' complaints that A-levels did not prepare students well enough as reason to shake up the exams. A* grades have also been introduced to help institutions identify the top pupils.

Despite this, MPs on the committee said there was "no appetite" among universities to examine why the proportion of top degree grades had risen.

'Inconsistent' standards

They also suggested inconsistency in standards was "rife" between institutions and called for a national set of classification standards against which universities in England match their honours classes.

Anthony McClaran, chief executive of the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA) insists standards across UK higher education are "fundamentally sound".

However, the organisation has set up a quality assurance group with aims including to ensure there is "authoritative, publicly accessible" information on standards and to improve consistency of assessment.

Whatever the arguments about why a greater proportion of higher grades are awarded, there is little comfort for graduates facing stiff competition for work.

Over 15 years, the number of students awarded a 2:2 has remained fairly steady at roughly 77,000 to 81,000.

But graduate at that level today and you will find yourself up against almost 140,000 better-qualified rivals - nearly 30,000 more than you would have done in 1995.