What might the UK economy be like in future?

- Published

Proponents of a rebalanced economy call for a manufacturing revival

Rebalancing the economy - it has become a mantra in Whitehall, the Bank of England and the world of economic think tanks.

In essence, what it seems to mean is making more things and exporting them, and relying less on services.

To put it another way, manufacturing good - financial services bad.

Ministers also promote the idea of rebalancing away from the South East of England.

Hence a David Cameron speech on the economy in a former West Yorkshire textile mill and the announcement of a regional growth fund after a Cabinet meeting in Bradford.

People often hark back to a golden age when the UK was the "workshop of the world" rather than a "nation of shopkeepers".

This was a time when millions of workers streamed into factory gates in the morning and home again later in the day.

Most expected to have a job for life in their local community's dominant industry, just like their parents and grandparents.

The UK exported and made a surplus on its trade with the rest of the world.

'Financial sector at fault'

Under this argument, the golden age was tarnished as manufacturing declined under competitive pressure from developing economies.

Skilled workers were obliged to downgrade to shelf-stacking jobs.

The UK, so this line of thinking goes, had to resort to making money from a bloated financial sector that dragged the economy into boom then bust.

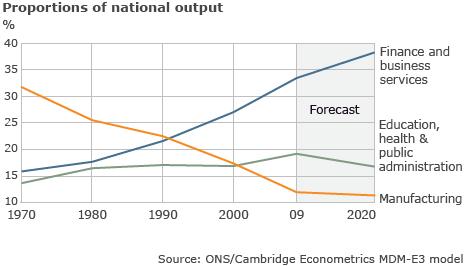

Chart 1 demonstrates the decline in manufacturing as a share of economic output (GDP) from 1970 to 2000 using official data and then forecasts from 2009 to 2020.

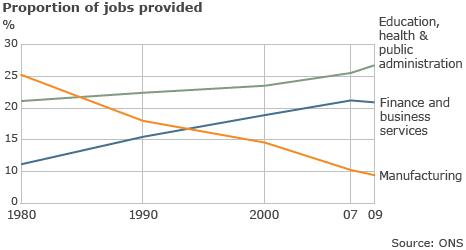

Chart 2 using official data shows a similar pattern for employment from 1980 to 2009.

Some of the rebalancing proponents would like to see manufacturing restored to its former glory with millions more jobs created, while the services sector is allowed to wither on the vine.

Others believe its sensible for a new-look economy to evolve - less reliant on borrowing and imports and more focussed on exporting to balance the international trading account.

Technology growth

Few disagree that the UK urgently needs sustainable economic growth to restore jobs and tax revenues.

But planning a route map will be far from simple.

And the shape of the final destination is far from clear.

A recent report from Oxford Economics and the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (Nesta), the lottery backed fund that invests in start-up companies, reached some interesting conclusions.

It argued that boosting manufacturing's share of economic output across the board was "implausible".

It suggested that a focus on high technology sectors was the most realistic option.

This would not necessarily create large numbers of jobs but would stimulate growth in internationally competitive businesses.

Such a strategy might also help stimulate growth outside the South East - the computer gaming industry based in Dundee is one example of a flourishing high tech centre.

Manufacturing decline

Manufacturing as a share of economic output has been declining for years

The coalition has made rebalancing a high priority.

So where are current policies taking the economy?

We asked the forecasting group Cambridge Econometrics to look at the future shape of the economy.

Its modelling incorporates the important measures set out in the June Budget, for example the spending cuts and VAT increase.

The Cambridge forecasts are intriguing (also shown in Chart 1).

They suggest that manufacturing's share of economic output will continue to decline.

Financial and business services will carry on expanding to the highest share in modern times.

The government share (education, health and public administration) falls back to roughly where it was in 2000 before the big spending increases under Labour.

So in 2020, under these projections, the UK will be even more of a service based economy.

Major contributor

The rebalancing champions may be dismayed by that.

The government might argue that it will take time for its growth policies to evolve and that future forecasts might throw up a different scenario for 2020.

Some might argue that there is nothing to be ashamed of with manufacturing declining as a share of GDP.

Nesta points out that business services is the largest contributor to growth and will continue to be central to the UK economy. Returning to a golden age is never easy and it's often not desirable.

Looking through rose tinted welding goggles may not be helpful.

Looking through the telescope at how competitor nations are shaping up and working out what goods and services to export to them will be the real challenge for businesses, governments and think tanks.

Hugh Pym is the BBC's chief economics correspondent. Andrew Evans is a statistician on secondment from the Office for National Statistics.