How 'rotten' is France's politics?

- Published

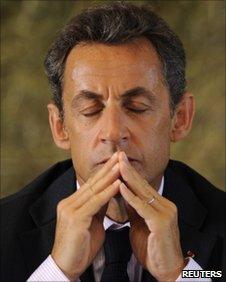

Critics accuse President Sarkozy of having broken "moral rules"

Claims of corrupt links between a French billionaire and top politicians have not just shaken Nicolas Sarkozy's presidency - they have revived deeply held suspicions that something is rotten in the state of France.

"We are in a banana republic and the French can't take it any more," a dissident right-wing MP said last week - even before the latest allegations that L'Oreal heiress Liliane Bettencourt had showered right-wing politicians with cash.

Marianne, a left-wing magazine, wrote on its website that under President Sarkozy "all the moral rules required in pursuit of the public interest" had been broken.

Following claims made by Ms Bettencourt's former accountant, prosecutors are now investigating whether the billionaire illegally funded Mr Sarkozy's presidential campaign in 2007.

Cynicism

Mr Sarkozy and Labour Minister Eric Woerth, who was then treasurer for his campaign, strongly deny wrongdoing.

But the inquiry is bound to reinforce cynicism in France, where public life has been poisoned by political-financial scandals for more than two decades.

In 2004 former Prime Minister Alain Juppe was given a suspended jail sentence over illegal funding of the main right-wing party in the 1980s and 1990s. Investigations into former President Jacques Chirac's possible role are continuing.

Other prominent cases have highlighted illegal commissions on foreign arms deals allegedly used to fund French campaigns.

One pending inquiry, involving the sale of submarines to Pakistan in 1994 when Mr Sarkozy was budget minister, may come back to haunt the president.

The irony is that the explosion of funding scandals in the past two decades has coincided with unprecedented attempts to clean up France's political life.

It began in the late 1980s, when it was revealed that the then-governing socialists - among others - had set up bogus consultancies to collect kickbacks from firms bidding for public contracts and channel the cash back to party coffers.

Resulting public outrage led the government to pass France's first law on political finance in 1988.

This set strict limits to donations and spending, instituted monitoring bodies, and - crucially - public funding of parties to try to end their dependence on interested corporate cash.

'Big change'

In 1995, a further law banned contributions from companies and non-profit profits bodies. Political parties, however, were still allowed to give to each other.

Individuals are also allowed to make donations. Those are currently limited to 7,500 euros ($9,500; £8,300) a year for a party and 4,600 euros for a candidate.

Furthermore, any donation above 150 euros must be made by cheque. The current investigation in the Bettencourt case is designed to determine whether these limits have been broken.

Do the ongoing scandals show that the reforms have failed and that corruption is as rife as ever in France?

Not necessarily. The convictions that have made headlines in recent years are over abuses committed before 1995.

Denys Pouillard, a political scientist who heads the Paris think-tank Observatory of Political and Parliamentary Life, believes French politics is now much cleaner and more transparent than it was in the 1980s.

Prosecutors are investigating if Ms Bettencourt illegally donated money

"There has been a big change," Mr Pouillard told the BBC News website.

But although abuse is now far from widespread, the reforms have had side effects that need tackling, Mr Pouillard says.

One unintended consequence is a proliferation of political parties drawing public funds.

Fewer than 30 political parties were registered in 1990. Last year, the number was 10 times higher, according to official figures.

Some of those parties have been set up by cabinet ministers. The Bettencourt case has highlighted an "Association Supporting the Action of Eric Woerth" - to which the heiress gave an entirely legal donation of 7,500 euros.

Across France, local bosses have been busy creating similar groups.

According to Mr Pouillard, the sole purpose of many of the smaller parties is to collect funds.

"A lot of parties receive public cash but have no activity," he says. "There are questions about the existence and legitimacy of those structures."

'Satellite groups'

Furthermore, according to analysts, some of those small groups could act as conduits for individual contributions on behalf of bigger ones.

As donations between parties are allowed, a donor can legally circumvent the limit on donations by giving to several outfits linked to a single one.

A 2006 report by the body monitoring political finance states: "Greater freedom to set up political parties has encouraged the setting up of satellite groups."

Mr Pouillard agrees. The goal of many of new parties, he suspects, is to pool 7,500-euro donations which will eventually find their way up the food chain.

No root-and-branch reform is needed, Mr Pouillard says, but loopholes need to be closed and stronger monitoring systems set up to reassure French voters that they do not live in a banana republic.

- Published7 July 2010

- Published7 October 2013

- Published6 July 2010

- Published4 June 2010

- Published3 June 2010