What does women bishops decision mean for the Church?

- Published

Traditionalists had wanted to able to bypass women bishops

It has been clear for several years that the Church of England's synod wanted to ordain women as bishops.

But that left a critical question - what concessions should be made to traditionalists who objected?

During a long weekend of impassioned and sometimes emotional debate, it decided that the concessions being sought came at too high a cost.

Traditionalists had wanted to be able to bypass a woman bishop and bring in a male alternative acceptable to them, to perform important functions such as ordaining new clergy.

But the synod decided that would undermine the authority of women bishops and consign them to "second class" status.

It voted to allow women bishops to decide the identity of any male bishop coming into their dioceses to work, and what he could do.

Traditionalists on the Catholic wing of the Church have long warned that many of them would rather leave than tolerate a situation they regard as deeply wrong.

Their objections include their belief that, as Jesus chose only men to be his apostles and therefore to lead the early Church, women cannot take that role.

'Constructive dismissal'

On the Protestant wing of the Church, conservative evangelicals insist that the Bible dictates that men should lead - both their own households and the Church.

One traditionalist described the synod's decision as "constructive dismissal".

But there is reason to think that rather fewer clergy will leave the Church than the approximately 450 who did so after women were first ordained as priests in 1994.

Although a legal bar was placed in the way of women's ordination as bishops at that stage, the whole Church could see which way the tide was flowing.

Traditionalists who felt most strongly had the opportunity to leave then, and younger ones have become priests knowing that they might eventually have to serve under women bishops.

But even where bishops, priests and lay people decide to stay, they may become part of a disgruntled minority whose unhappiness could threaten the harmony of the Church.

The synod was not to be swayed and its determination to avoid undermining the authority of women bishops was driven partly by the fear that its attitudes were dangerously out of step with wider society.

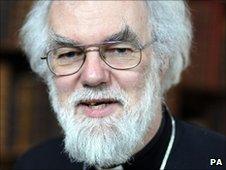

Rowan Williams says holding the Church together is "difficult"

One liberal priest - Canon Robert Cotton - said he was worried that the Church could turn into a sect, refusing to listen to the wisdom that was available in the outside world.

The argument focussed on part of the legislation providing for exemptions for the Church from the Equality Act 2010.

Because it is the established - or state - church, a parliamentary committee will consider the legislation allowing women bishops to be created.

A lay member of the Synod and former MP, Robert Key, warned that the Church could not count on Parliament to give it the "power to discriminate against women".

Mr Key warned that it could become "a dwindling sect, a privileged minority, a reactionary husk".

But the Bishop of Durham, Tom Wright, roundly contradicted Mr Key, telling him that when the Church started to follow the dictates of contemporary society, it "would cease to be the Church".

'Spirit of the times'

Liberal Anglicans pointed to the loud applause Dr Wright received - some people standing to clap - and suggested that there was a deep-seated reluctance among synod members to adapt to the spirit of the times.

That could become an issue when and if an actively gay bishop is appointed.

Some evangelicals have seen this debate - and its discussion about getting exemptions from being overseen by a bishop you do not like - as a dress rehearsal for a future debate about gay bishops.

Conservative evangelicals have challenged the assumption that the current system of diocesan bishops who control everything within their domain should continue.

They say this system of "mono-episcopacy" is not demanded by the Bible, nor by traditional practice.

The General Synod is up for re-election in the autumn

They favour the sort of overlapping jurisdiction that the Archbishops of Canterbury and York seemed to envisage in the compromise plan narrowly defeated by the synod.

It would have meant a sort of "job-share" in traditionalist parishes, with a woman bishop allowing some functions to be carried out by a male alternative who had a large measure of legal independence and autonomy.

Largely because the archbishops gave their personal backing to the plan, it received a majority of the vote in the synod, failing only because the vote took place separately in the three "houses" of bishops, clergy and lay people.

Clergy voted against the plan by a margin of just five votes.

The legislation will now be sent to dioceses for what is almost certain to be their approval and will return to the synod, probably in February 2012.

To become law it will have to achieve a two-thirds majority in each house of the synod.

Given that the synod faces re-election this autumn, that's not a foregone conclusion.

If it overcomes that hurdle, the legislation will go before Parliament, and then to the Queen for the Royal Assent.

The first women bishops might be appointed in 2014.

It will seem a long while since the Church decided 30 years ago that there was no theological reason why women should not take the role.

But Dr Williams was unwilling to allow the synod to feel it had entirely solved the problem.

At the start of the final session of discussion, he reminded members that it was "desperately difficult" to hold the Church together.

He said it was "not the end of the road" for attempts to preserve unity, and said "we are profoundly committed by a majority in the synod to the maximum generosity that can be consistently and coherently exercised towards the consciences of minorities."

"We have not yet cracked how to do that," he said.