Police cuts: Why officers are taking to the streets

- Published

- comments

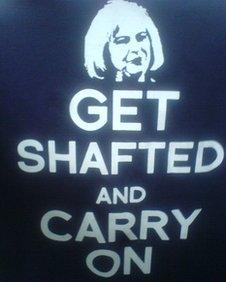

One of the T-shirts worn by protesting officers

Thursday's demonstration in London by police was a culmination of more than a year of increasing tension between the rank-and-file officers and the government over broader reforms.

Officers have been pouring their anger out online - read the furious (but also rather entertaining) Constable Chaos blog, external to get a flavour of how officers feel.

On Thursday, they took to the streets in a last-ditch effort to see off major changes to how the job is done.

Police officers cannot strike. The last time they did so was in 1918 and 1919. The government feared anarchy and very quickly banned officers from striking ever again, external.

So Thursday's protest was to all intents and purposes a traditional piece of industrial action, albeit by people who could not withdraw their labour. The officers who marched took the day off work and they weren't in uniform.

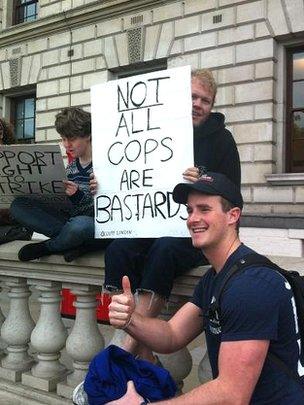

Love across the divide: Occupy London protesters come out to support the police

Some 16,000 wore black baseball caps to represent the number of officers that the Police Federation predicts will be lost by 20% budget cuts in England and Wales. Many of the others wore white caps with the words "Enough is Enough!".

The Police Federation estimates that more than 30,000 of its members came to London. If that's accurate, it represents roughly a fifth of all officers in England and Wales.

Police strength reached a record high of roughly 143,000 towards the end of the former Labour government after years of ministers throwing cash at recruitment.

Home Office figures show numbers have fallen back to about 136,000 officers, external, the lowest figure for a decade. There are approximately 70,000 further police staff, who perform roles that don't necessarily require a sworn officer, but their numbers are falling too.

But coalition ministers say this is not a numbers game. They say Labour ducked for years the bigger issue of what you do with the officers you have.

Fundamental shift

On and off-duty: Marchers applauded by working colleages

At the heart of this strategy is a lot of work on technology and modernisation - but also two reports by Tom Winsor, external, the tough-talking former rail regulator.

He has proposed a fundamental shift in how the police are paid - awarding the officers who are taking the greatest risks in front line jobs while cutting payments and allowances that are not longer justified in the modern workplace. A response officer - the Pc who has to chase the knife-wielding mugger - would earn more than the colleague in the control room.

His second report argued that it was about time that the police were professionalised and stopped viewing it as some kind of blue collar job for life. His proposals include lifting the ban on compulsory redundancies and potential pay cuts for officers who fail fitness tests.

Even more controversially, he proposed ending retirement after 30 years service - typically meaning at 50 - and said potential high-flyers should be allowed to enter at inspector level, rather than fight their way up the ranks. He called for recruits to have a minimum of three A-Levels and promotion based solely on skills - not time served.

"Policing today is entirely different and yet so much of its ethos is of the past," he said.

Morale rock bottom

The Police Federation sees Winsor Part Two as the "final nail in the coffin". It predicts that the reforms, along with cuts, will lead to a rise in crime.

As we walked alongside the Thames, Mike, a sergeant from Manchester, said that ministers needed to grasp the real challenges faced by his squad.

"They only deal with crime 40% of their time," he said. "The other 60% of the time we are dealing with other agency's work - the NHS, social services, marriage guidance if we're going to people's homes to sort out a domestic.

"We are the backstop for everyone else - but we don't have a backstop. If a job is passed to us, we deal with it. That's what we do and we accept that."

The Police Federation's battle with the government is bigger than pay alone. Ministers want savings by using more (cheaper) civilian staff in back-office roles. This has led to a vexed question about where the front line ends and the back office begins.

John Marshall, a Metropolitan Police sergeant, said ministers had only given one side of the story, external.

"The problem is that they keep going on about these back-office roles [that police don't need to do] but they have not defined what they are," he said.

A sign of things to come?

"There are obviously jobs that have to be done and all that will happen is that front-line officers will be redeployed to the back office. It's taking them off the streets."

One of the most dramatic out-sourcing initiatives so far has seen 200 police staff in Lincolnshire Police transferred to private security conglomerate G4S.

PC David Asher from the force said, external: "I don't know how [the G4S deal] it's going to end up. There are going to be some benefits from the deal, such as new police stations. But it is going to impact on civilian staff that we have who are loyal to the force and there is the point that we are not in this for the profit."

Policing minister Nick Herbert has written an open letter to all officers, external appealing to them to accept all of the changes as good for their service.

"All organisations have to keep pace with the modern world," he says. "I know that the spending reductions which police forces are required to make are challenging, but they are necessary."

He says the changes are not just about cuts - but about professionalisation, modern training, equipment and cutting bureaucracy. He's also given a guarantee that private companies will not be given powers of arrest and detention.

"Police officers do difficult and often dangerous work and cannot strike. I am determined that we recognise this, treat officers fairly and pay them well," says the minister.

"But we also need to update the service to ensure that the hardest-working officers doing the most difficult jobs will be rewarded, and to acknowledge and reward professional skills and continued development."