Cosmic coincidence on the road to Glenelg

- Published

- comments

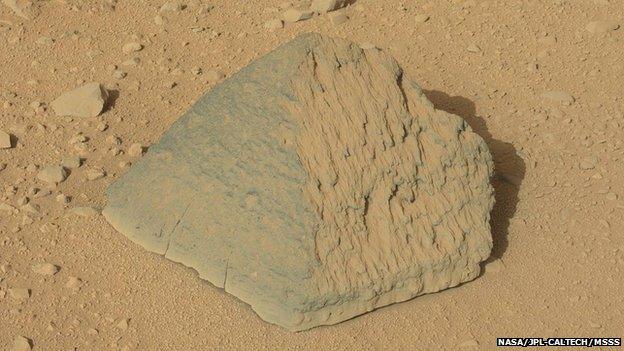

The rock known as Jake Matijevic: Anything but dull

This is a tale of a wonderful coincidence that ties together Mars, the Canadian north-west, Scotland and 100 years of geology. Bear with me because it takes a little while to pull all the threads together, but it's worth it, I promise.

It starts with an object called Jake.

I wrote last week about a dark, pyramid-shaped igneous rock on the Red Planet that had just been investigated by Nasa's Curiosity rover, external.

It certainly looked cool and it caught the imagination because my report subsequently clocked more hits that day than any other news story on the BBC. Never mind wars, politics and the economy - everyone, it seemed, wanted to find out more about this unusual, 25cm-high rock sitting in a crater almost 300 million km from Earth.

When Curiosity approached the volcanic rock, there was never really any expectation that it would pique great excitement.

It looked like just another dull piece of basalt, so much of which litters the Martian surface. But the science team on Curiosity needed a target to try out the first close-contact work using the rover's arm-held X-ray-spectrometer, APXS, external. So the dark pyramid was chosen and informally given the name Jake Matijevic, external in honour of a recently deceased rover engineer.

The science team needed a target to start some close-contact work with APXS

The results of the investigation by APXS, and the rover's laser instrument, ChemCam, external, revealed the rock to be anything but dull.

The science team likened its chemistry to some relatively rare but well-studied alkaline rocks on Earth found on oceanic islands such as Hawaii and the Azores, and also in rift zones like the Rio Grande. On Earth, such rocks typically form from relatively water-rich magmas that have cooled slowly at raised pressures.

The Curiosity team compared their formation to the fractionation that occurred in the old colonial method of making apple jack liquor. This process saw barrels of cider left outside in winter to partially freeze. As the barrels iced up, they would concentrate the apple-flavoured liquor.

Likewise, cooling magmas under pressure will crystallise and concentrate residual fluids. Jake was a consequence of those residual fluids, eventually solidifying just inside a Martian volcano or in a lava flow.

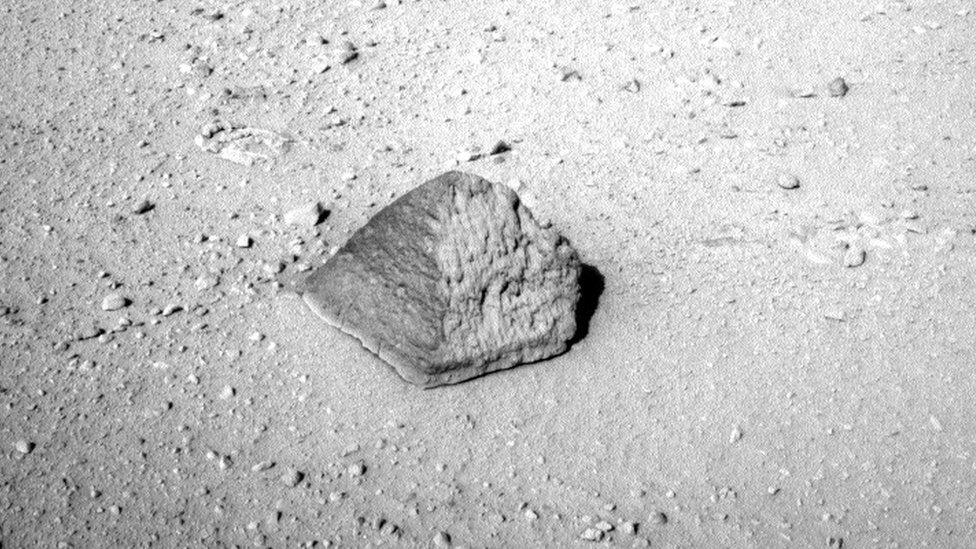

The rover landed in Gale Crater and started moving towards Glenelg. During the trek, on the 43rd Martian day of the mission, Curiosity came across the pyramidal rock

Well, everyone loved the apple jack analogy but a number of you got in touch to ask for the exact classification of the rock.

"What scientific name are they giving to the lithology?" you wanted to know.

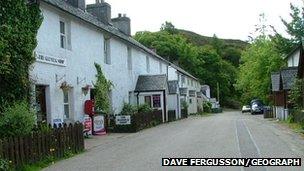

Glenelg in Scotland is enjoying being in the international - and interplanetary - limelight

And so I went back to rover scientist and petrologist Prof Ed Stolper, external, who had presented the Jake results. Could he provide one?

This was not straightforward, he explained. Although APXS and ChemCam will tell you which chemical elements are present, they don't tell you how precisely those atoms are arranged into the crystalline structures that make up the rock, and both this mineralogy and the chemical composition are ideally needed to assign a rock name.

So there's a bit of guesstimation going on here. From the chemical composition, you have to work out the most likely mineralogy.

As mentioned, Jake has much higher amounts of alkali elements, metals such as sodium and potassium, than previously analysed Martian rocks. And that has Prof Stolper and the rest of the rover science team leaning (with a lot of caveats) towards a classification that sits on a well-established sequence of alkaline igneous rocks - one that goes by the name "mugearite".

And this is where we come to the great coincidence.

If you've been following the Curiosity rover story closely, you'll know that scientists on the mission have been using names taken from Canada's Northwest Territories to label the places the rover is visiting.

The Canadian north-west has some ancient rock formations, similar in age, we think, to those found in Gale Crater, Curiosity's landing site.

The naming system makes it easy for everyone to understand what's being discussed when a particular location comes up in conversation. So, for example, the rover is currently making its way to a place everyone is referring to as Glenelg.

This name is taken from a particular rock unit in the Northwest Territories, but it has an even older lineage - one that goes back to a small Highland settlement in Scotland.

This version of Glenelg is found on the western edge of the mainland, right by the water channel separating the Isle of Skye from the rest of Scotland.

Now read what Prof Stolper told me: "The 'type locality' for mugearite [i.e. the place the rock was first discovered, or at least defined as a distinctive rock type] is Mugeary, which turns out to be on Skye only 25 miles west of Glenelg.

"The fellow who named the rock type [in 1904] was Alfred Harker, external, the most influential British petrographer/petrologist of the first third (or so) of the 20th Century.

"Given the nearness of Mugeary and Glenelg, I consider it to be a great cosmic coincidence that on its way to Glenelg, the Curiosity rover found a rock that can legitimately be called a mugearite!"

Life has a habit of throwing up such remarkable connections. Glenelg was identified and named on Mars four weeks before Jake was even seen.

Curiosity only landed on the Red Planet in August but already it has returned some truly exciting science. And to think we have another couple of years at least to go on this mission.

The light-coloured tones two-thirds up this panorama from the rover are in the region known as Glenelg

- Published12 October 2012

- Published23 August 2012