Mardell: Conservative Kentucky torn on Obamacare

- Published

Residents of Kentucky, one of the unhealthiest states in America, talk to the BBC about their hopes and concerns about Obamacare

Varnita Willingham is telling a doctor her bad news. The cancer is back.

It is enough of a worry on its own. But almost as bad, she doesn't know how she'll pay for the treatment she urgently needs.

She is just the sort of person President Barack Obama hopes will be helped by his radical changes to America's healthcare system.

Ms Willingham suffered a nearly fatal heart attack following her last spell of chemotherapy. It is hard to know how the 56-year-old former teacher keeps cheerful, but she does.

"I have a 21-year-old, you know, and she's on edge about it," she says. "But she knows that, with God, we're going to make it because He's the one who holds the key."

But the key to how she might pay for her healthcare was turned in Washington.

'A slow process'

Willingham has attempted to sign up for health coverage under Obamacare

I met Ms Willingham at University of Louisville Ambulatory Internal Medicine Clinic, in Kentucky, where more than half the patients have no health insurance. She's convinced that the introduction of the Affordable Care Act - nicknamed Obamacare - will be a boon.

"Obama really has done something great for the United States," she says. "People complain but nobody's ever going to be totally satisfied."

They certainly do complain. In a conservative state such as Kentucky, many see it as unwarranted government intrusion, an un-American extension of the welfare state.

But Obamacare is also in trouble because it is complex and complicated.

Journalists always like to think they can get to the bottom of things. I tell you, it is currently impossible to say what Obamacare will mean for many families.

Ms Willingham has been told she will benefit from the billion-dollar expansion of the states' plan for those on low incomes - Medicaid. That's probably true, but she can't find out for sure.

"I think it's going to make a difference to me," she says, "once I get more knowledgeable about it."

She said she applied for coverage on 1 October but no one has followed up with her.

"I know it's a slow process," she says. "I listen [to] the news and I heard all the minor details and people bickering back and forth but I'm going to wait because I know there's going to be a plan for me."

'A better opportunity'

Many patients at the Ambulatory Internal Medicine Clinic at the University of Louisville do not have health insurance

Walk just outside the clinic and you see at once the uphill struggle the doctors have. Just by the sign for the stroke clinic, a family - all overweight, all puffing furiously - cluster around a cart selling hamburgers and hot dogs.

Dad obviously isn't hungry. He's standing underneath a sign that reads "Cancer Center" with other patients and visitors, leaning against a low concrete wall, smoking.

Kentucky is the worst of the 50 US states for smoking and cancer deaths, and not far from the bottom for heart disease, stroke and premature death.

Obamacare is designed to help places like this. The chief resident at this clinic, Dr Monalisa Tailor, thinks it will.

She tells me right now she sometimes simply can't fulfil the most basic part of her job - diagnosing what's wrong with a patient. Obviously sick patients forgo medical testing because they are unable to afford it.

"Something like Obamacare or the Affordable Care Act is going to give these people a better opportunity to have better healthcare," she says. "That's what we need."

'Begging for insurance'

President Barack Obama has campaigned vigorously on behalf of his signature healthcare law, nicknamed "Obamacare"

But not even Obamacare's fiercest fans would claim its launch has gone well.

The rollout of the national website for people to find insurance schemes that suit them has been a shambles.

The president has been forced to apologise and opponents are gleeful. He's pointed to Kentucky as one of the places where it is working, at a local level. An estimated 32,000 people have already signed up.

But when I make it to the library in the small town of Bedford, it is clear they're having some problems of their own.

Christie Hartlage and the man she is trying to sign up to the state's "kynect, external" scheme sit glumly at a table, staring at a mobile phone, listening to that teeth-grinding "thank you for holding" music.

Eventually someone comes on the line and, with apparently some satisfaction, trots out a response: The man cannot continue the enrolment process until he returns to the library with a government-issued identification card.

"Sorry it didn't go a little more smoothly," Ms Hartlage says to the man. They arrange to meet up the following week.

She insists that such setbacks are a small price to pay.

"They are really begging for insurance," she says. "This programme is wonderful and people are flocking to become part of it."

'Drastic difference'

Kentucky is home to wealthy numerous horse farms - but many, many poor people

The man, Sam McAfee - a Vietnam veteran who is passionately worried about the state of the economy and the low wages paid in the area - is unfazed by the difficulties with Obamacare.

"For anyone who is making less than $25,000 (£15,625) a year, it is going to make a drastic difference," he says. "Instead of saving up for a month or two to take their child to a doctor, they can go when they need a doctor. This is the answer for the people of this country who are not wealthy."

Indeed, Obamacare is such a hot political topic because it sharpens and highlights the country's deep divide of income and ideology.

Kentucky, with its rolling fields and sleekly muscled race horses, can feel very rich. But there are poor aplenty, and many look ground down, worn out and ill.

It is a traditionally conservative state, where Mr Obama is deeply disliked - more than 60% voted for Republican candidate Mitt Romney in November. Both senators are Republican.

But the governor is a Democrat and that is the key to the apparent enthusiasm here.

Republican states in the south and elsewhere have shunned the law, refused to set up their own health insurance schemes. That is why the problematic federal system was set up in the first place.

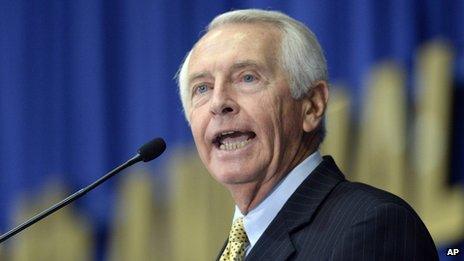

Kentucky Governor Steve Beshear has seized on the new law to promote his own plan. Critically, the big uptake is because of the state's poverty - it is not mainly because people without insurance are showing enthusiasm for being forced into private schemes.

It is because of a $1.3bn expansion of the plan that helps the poorest - Medicaid.

Mr Beshear has dramatically increased the number of people covered by lowering the requirements for joining. He's also pushed a big increase in what it covers. He says 640,000 people in the state don't have insurance and more than 300,000 will now be covered by the expanded Medicaid.

"We needed some transformational tool that would allow us to pull our car out of the ditch. We are not only going to have such a better quality of life for all our people but a healthier workforce," he said.

"It's going to lift this whole state up."

Mr Beshear says a state-ordered economic analysis found the law would put $15bn into the economy over the next ten years and create about 17 million new jobs over the next eight, while aiding the state government's budget.

'A greater burden'

Beshear has been a vocal proponent of Obamacare in his state, which is also deeply conservative and voted strongly against Obama

But many will remain unhappy. I met three people, all Republicans, in a Louisville coffee shop. For all of them, it is both political and personal.

Wesley Scott is a 21-year-old student. In theory, Obamacare means he could go on his parent's healthcare plan. But they don't have any.

"It means higher cost. It means a greater burden on a college student who is already tens of thousand of dollars in debt," he said. "I absolutely have to have it because if I don't get the insurance, I have to pay the fine. If I didn't want to get car insurance, I could take a ticket or not drive."

And he says it goes down badly here.

"One of our state mottos is 'an unbridled spirit'," he said. "People don't want to be held back, they want to have control over their own destiny and Obamacare limits that for a lot of people."

Paul Schaffer, who is in the education business, at the moment has what is known as "catastrophic care", which means he is covered for things like cancer and heart attack but not for more humdrum conditions.

He was happy budgeting for the odd trip to the doctor but he says Obamacare dictates that insurance has to be more comprehensive, so it is going to cost him more.

"It was manageable," he said. "It was a little bit of money every month. Now I am going to have to pour more money into it. The new plan is $50 a month more than my current one and it's not as good as what I have."

'An American thing'

Scott Piland is just the sort of person Obamacare was designed to help. It ends the scandal that some people simply can't get insurance.

He has a cyst in his brain which he says doctors have told him will have no impact on his life.

But "no one will touch with me with a 10ft pole", he said, referring to insurers.

He says he does not want to be forced into having to get the newly available insurance - he's learned to live without it.

"What I have been doing quite successfully is self-pay" he said. "I am willing to take the fine. It's an American thing - we don't like to be told what to do by our government."

All three men agree that the intentions of Obamacare are good - but they don't want to be made to pay more.

Barring unexpected triumphs or disasters, the law will be Obama's legacy - the biggest change he has wrought in America, a central part of how his term in office will be seen by future generations.

Many who now are for it or against it because of their politics may change their mind, one way or another, when it beds down and starts to change their lives for good or ill.

These first few months in places like Kentucky will be critical.

- Published30 October 2013

- Published29 October 2013