Are Rio's shanty towns falling into old schisms?

- Published

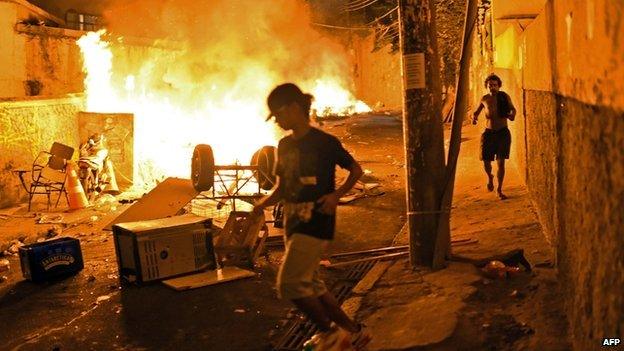

Brazilian police blame recent violence on gangs' attempts to regain turf lost through the pacification policy

I spent over an hour in the Pavaozinho favela on Wednesday, looking over the aftermath of last night's violence and trying to speak to people about what happened and why.

I must have spoken, or tried to speak, to dozens of residents of the shantytown but not a single one would go on the record.

Some did talk to us privately but such is the level of mistrust between locals and police that everyone here fears retribution if they talk openly to the press.

That is the perhaps the biggest concern for the Rio state government as its much-vaunted "pacification" policy starts to unravel, not just here in Pavaozinho but in other communities too.

According to the state government and the Pacification Police themselves, it is the criminal gangs, who deal mainly in crack cocaine, trying to move back into to areas from where they'd been previously expelled that are at the root of the problem.

But it's more complicated than that.

Around the clock

Pavaozinho (in the Cantagalo district of south Rio) is perhaps the most central of all the favelas.

Built, like most informal communities, on a steep hillside, it overlooks Copacabana beach. The main entrance to the favela is via the main thoroughfare of Nossa Senhora da Copacabana.

It is also one of about round 40 communities that, in recent years, have been "pacified".

In effect that means putting a permanent police presence inside the favela, from where regular patrols come and go and which is staffed around the clock.

Pavao favela is one of Rio's poor districts targeted by the pacification programme

It's a long cry from the days when most, if not all of Rio's shantytowns were only visited by police in heavily armed lightning-style raids, more often than not in pursuit of a suspect.

By and large the pacification project had been considered a success, not only making the area safer for residents but also driving out the drugs gangs that had been established there.

It also made some celebrated favelas like Vidigal more desirable places to live.

It is close to the city centre with often stunning views of the beach. Residents soon began to own their homes and many had well-paid jobs in the city.

Heavy-handed tactics

For some reason, perhaps particular to the area or circumstances, tensions have been high in the Pavaozinho favela for months.

According to police, the crack cocaine gangs are trying to move back in and reclaim their turf.

It's a lucrative business and this part of Rio is prime real estate in more ways than one.

The locals accuse the police, in turn, of being heavy-handed.

Residents were caught in a shoot-out between riot police and a local gang in Pavaozinho on Tuesday

On a recent patrol around Pavaozinho, as I held back from the main police unit, I was amazed to feel the level of mistrust and tension.

"They're always beating us for no reason," one young boy told me as we walked through the narrow alleyways.

They accuse the cops of painting them all with the same brush, as if all the boys here were inevitably going to become hardened gang members one day.

The Brazilian authorities are trying to drive away gangs from favelas ahead of the World Cup in June and July

The "mata" or the "jungle" in the very top part of this steep favela is particularly dangerous.

This is where police allege many of the illegal guns owned by the gangs are stored and it is certainly one part of Pavaozinho where the police cannot claim to be in full control.

It was, allegedly, the heavy-handed and very unsubtle nature of policing and law enforcement here that led to the clashes on Tuesday night.

A young local man, Douglas Rafael da Silva, was killed in what now appears to have been a shooting.

According to his family, the 26-year-old - who was a professional dancer on a local TV show - was chased, beaten and killed by police who mistook him for a gang member.

What next?

Brazil's police have a fearsome reputation for violence.

In turn, they say that in the hours of darkness in the hostile alleyways of the favelas they are in fear of their lives - pursuing armed criminals who know the lay of the land much better than they do.

Pacification may have brought some relative calm to many of Rio's favelas but it is a policy that is in danger of falling apart because the authorities have failed to build upon their early inroads.

Friends of Douglas Rafael da Silva, whose killing sparked off deadly protests in the city, paid their respects

You rarely hear in these parts of joint police-community projects aimed at establishing permanent structures and partnerships.

The talk is always of confrontation, or of whichever side (them or us) has the upper hand.

This is all of interest now, especially to the international media, because of the thousands of visitors who are expected in Rio for the forthcoming World Cup.

Some, who may have sought out the cheaper hostel accommodation in the favelas, might now be put off and the risk of petty crime on Rio's streets is undoubtedly more palpable.

But the real tragedy is that a city that had, in recent years, started to feel safer and more inclusive - a Rio for everyone who lives here - is once again falling into its old schisms and divisions.

- Published23 April 2014

- Published5 April 2014

- Published31 March 2014

- Published21 March 2014

- Published27 February 2014

- Published21 February 2014